“An investor who does not do research is like a poker player who does not look at the cards.” – Peter Lynch

McCaw Cellular Communications was founded in the mid-1960s as a cable television provider who started pivoting to cellular technology in the mid-1980s. Buoyed by the birth of the high-yield market the firm started acquiring cellular licenses in some of the largest markets in the US, anticipating explosive growth long before the giant telecom operators made the business a priority. Throughout the decade it added licenses, upgraded services, expanded coverage and built out the first real national cellular network. On August 17, 1993 they announced a sale of the company for $12.6B to AT&T. Less than a month prior to that announcement, Craig McCaw sent a letter to his employees celebrating a corporate milestone: July 21, 1994 was the first day of profit.

How is a company with essentially no earnings worth over $12 billion? Was AT&T nuts?

Here’s another story.

Would you want to invest in a company that is profitable today but will generate negative free cash flow for the next 15 years while growing debt at a rate of 34% over that time?

I hope so. Because that’s what Wal-Mart produced from 1972-1986 and put up a return of 29% per year versus the S&P 500s 11%. I wrote in one of my first posts that Cash Is King. So was the market in a state of denial for 15 years rewarding a company with negative cash flow?

I’m reminded of examples like these when the financial press seems to obsess over whether “value” stocks will finally start to perform in line with the rest of the market (Figure 1). The fascination reared its head again last week when, on news of Pfizer’s promising vaccine, those designated value stocks outperformed the rest of the market handily. Commentators deliberated whether a rotation was under way that would lead this class of stocks to outperform over the future.

Figure 1: S&P Value (White) vs Growth (Yellow) over the last 10 years

Personally, I find most discussions on this segmentation either silly or disingenuous or both for a number of reasons.

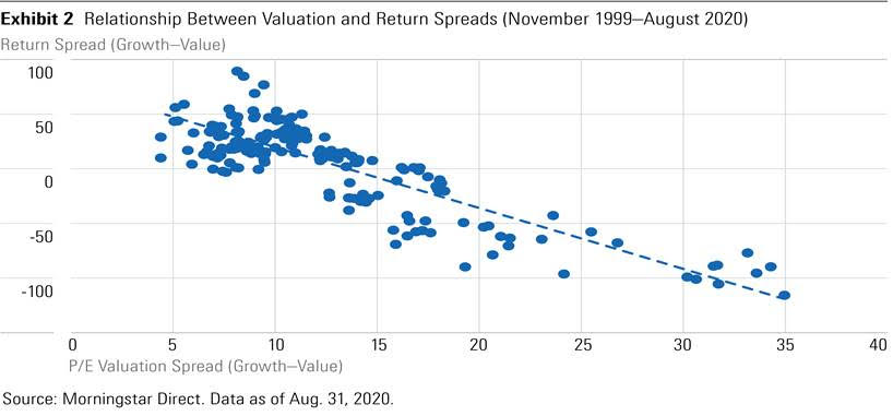

First, it confuses a value factor with an individual business. One is a statistical classification versus the other which is an idiosyncratic entity. But valuation is not the only piece of information embedded in a stock’s price. Growth, profitability, competitive advantages, management quality, etc. are also being discounted constantly. Thus, the only to isolate for valuation and capture this elusive value premium is to implement a trading system whereby some group of stocks meeting a valuation threshold are bought and recycling that exercise over and over at some periodic rate. For instance, the cheapest 50 stocks in the S&P 500 would be bought on January 1st, held for one year, and then sold at the end of a year in order to buy the new components at the start of the next year. That’s the methodology for capturing “value” to try and get the historical premiums so many are used to (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Historic Return Spreads Across Valuations

There’s nothing wrong with strategies that do this. They have their role. But I don’t know of a single fundamental manager that manages money this way. And why would they? Managing money this way could easily be automated. Rather, to my knowledge, only quant investors do because they’re dedicated to capturing the statistical phenomenon not because they find an individual business attractive.

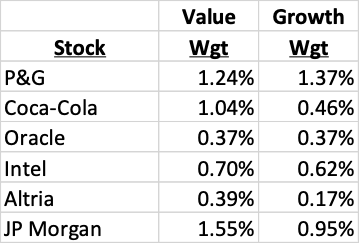

Second, these debates rarely look under the hood. If they did, they’d encounter some funny findings. In Figure 3, you’ll find the current weightings for a handful of blue-chip companies in both the S&P Value and Growth indices. Readers can decide for themselves, I guess, if Procter & Gamble is a value stock or a growth stock. I’m not sure how “valuable” it is that Intel’s competitive advantages are melting down right in front of them. Oracle has grown revenues below the rate of inflation for the last 5 years yet it somehow still gets categorized as a growth stock and has just as big a weight as it does in the Value Index.

Figure 3: Value or Growth

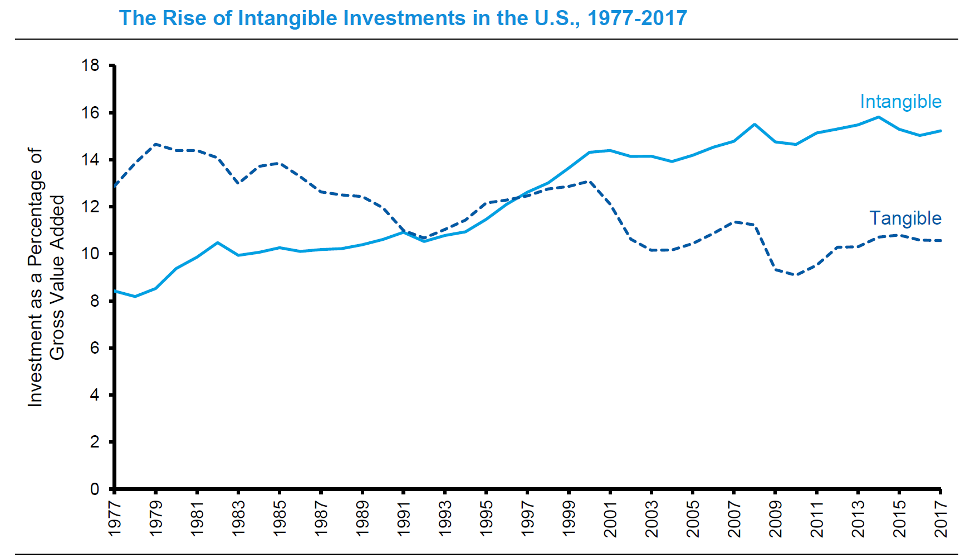

Third, these designations use too broad a brush to paint over an economy and corporate environment that has undergone significant changes in the last 40 years. In the 1980s, approximately 80% of corporate value was tied up in tangible assets: things you could see and touch like machines, manufacturing plants, etc. But today, the world has inverted. Instead, 80% of corporate value is tied up in assets that are intangible, like patents. I alluded to this in a piece a few months ago as well but such a transformation has enormous repercussions on short hand valuations due to the accounting treatment of tangible versus intangible investments.

Figure 4: The Rise of Intangible Investments (Morgan Stanley)

You may very well be reading this piece on a Windows computer, running an Intel chip, while drinking Starbucks coffee, wearing Nike shoes, as your smart speaker plays music in the background and each one of those individual products has its value thanks to decades and billions of dollars spent on research and development, advertising, software development and technical know-how. Yet all those expenses that generated the products millions of consumers know and love are treated the same as the salary of a corporate accountant.

Returns are generated from past investments but the problem with intangibles is being able to delineate between what is an expense or what is an investment because both are treated the same under today’s accounting rules. Some cash expenses that go out the door generate more cash in the future, and some are simply expenses that support the steady state of the business. Current accounting policies do not distinguish between the two but if an investor wants the know the path and trajectory of future earnings then they need to know what investments a business is currently making. The more a firm spends the more distorted the picture gets. Earnings are thus a blend of traditional income statement line items as well as a reflection of assets that would normally go on a balance sheet. As such, earnings get depressed on the surface, raising PE ratios, and scaring away so-called value investors.

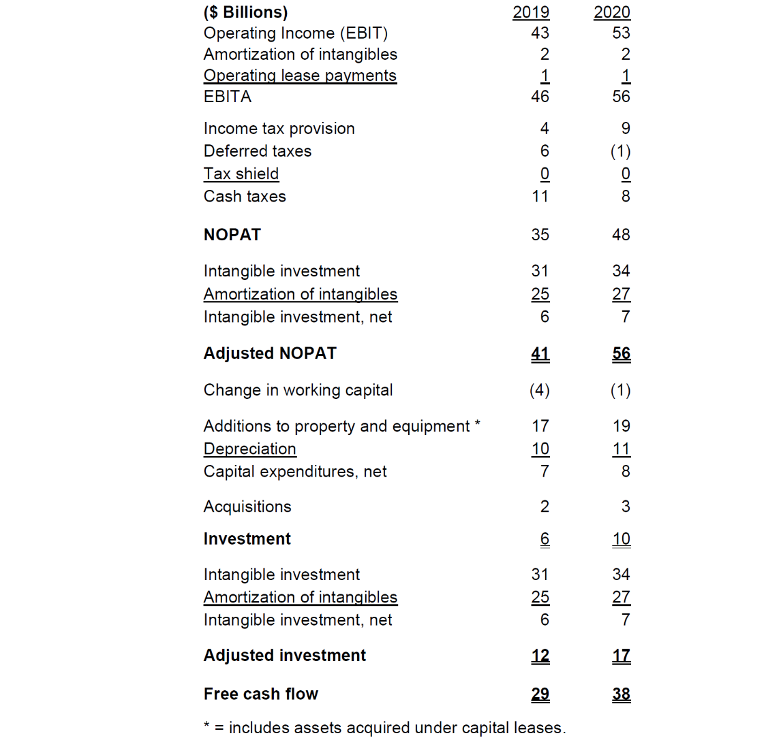

Take Microsoft as an example. If one were to understand it’s R&D expenses as investments in the future (as well as some of its expenses in SG&A), investments in its most recent fiscal year rise from $10 billion to $17 billion and Operating Profit after Taxes rises by 15% while ROIC remains an excellent 33%*. With results like this, any rational investor would want Microsoft to be investing as much as it possibly could if it is going to be generating returns like this, even if it skews the PE ratio upward.

Figure 5: Treating Intangibles as Long-term Investments for Microsoft (Morgan Stanley)

And this isn’t a scenario where we’re talking about a handful of companies being impacted by such a shift. Nearly 40% of companies listed in the US lost money in 2019, a rate more than twice as high when accounting provisions for intangibles were made in the 1970s. In fact, one study, after adjusting for the impact of intangibles, reported that ~50% of stocks over the last 30 years did not meet the definition of being a “value” stock.

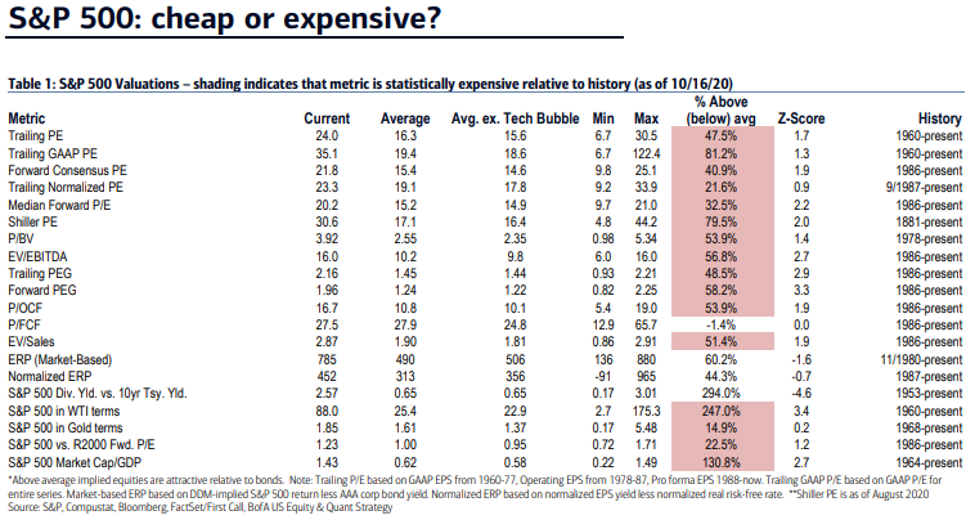

This is a massive transformation that has been going on underneath the surface for decades. In all actuality, this change shouldn’t be too surprising. Historically, economies transition either in part or in whole from agrarian, commodity-based economies to manufacturing to service and consumption led structures. The U.S. represents the starkest example of a country in those latter stages. No one argues that the U.S. is a consumption and service led economy, yet investors can’t seem to connect the dots on how such a change manifests into earnings. Is it all that surprising then that currently the market is currently expensive by every measure except Price to Free Cash Flow (Figure 6).

Figure 6: The S&P 500 in line with Past P/FCF average multiples (Bank of America)

Stepping back, my ultimate gripe with the debate and fixation of the investing community or financial media on this topic is more philosophical in nature. Isn’t growth valuable? If two companies trade at multiples slightly but noticeably apart but one has far superior growth prospects is a singular ratio going to encompass that? Isn’t good management valuable? Isn’t a moat valuable? Are we only going to count on earnings in 12 months? Do earnings that come 5, 10, 15 years from now not matter? The list goes on. Yet time and again investors proclaiming some badge of value continue myopically preaching some gospel that they themselves didn’t understand, missing the bigger picture.

Going back to the two examples I started with McCaw Cellular Communications may not have booked an accounting profit, but it produced over $450M in EBITDA and ~$200M in Free Cash Flow while investing for growth before being acquired. As for Wal-Mart, yes, it needed external financing but that was to finance a massive expansion of its stores. An astute investor would have noticed that Wal-Mart was producing ROIC of ~20% and that incremental stores were more accretive because of scale advantages in purchasing power, logistics and branding. With returns that high and a proven, defensible business model, investors had no problem underwriting capital to finance their expansion.

So will value investing work again? The short answer is yes. There will be a day when COVID-19 is behind us, the price of oil rises and interest rates increase, directly impacting and elevating Energy, Financials, Real Estate and with substantial knock on effects on Consumer Discretionary and Industrials. It’s these areas of the market that dominate the “value” tranche.

The longer and more appropriate answer is yes, value investing will work because it’s the only thing that ever has. Value needs to be taken in totality. A stock’s “cheapness” is relative to intrinsic value. What has made value investing work in the past, present and will explain its future success is not a ratio. It is differentiated and superior judgments. In this day and age with such computing power, segmenting the market into “cheap” and “expensive” portions is essentially costless. Automation, computing and algorithms have made predictions cheap and abundant. What is scarce is judgment. Buffett bought his first shares of Coca-Cola at a PE of 30, a multiple that was more than twice as high as the whole stock market. So called value investors looked upon and ridiculed him. It wasn’t a PE of 30 that made Buffett think Coca-Cola was cheap. It was his insight and judgment that by owning Coke he was “taking a tax on gulps” to use his words.

Investors proclaiming themselves to be of the value variety because of their predilection for a particular ratio never were real value investors. They strike me more as talking calculators, able to identify prices but not value when it’s right in front of them. Price is what an investor pays. Value is what they get.

*Credit for the Microsoft example and the ruminations on the impact of intangibles on accounting go to Michael Maubossin and Daniel Callahan of Morgan Stanley.