Value and Renewal

Value and Renewal

-

Author : Joel Charalambakis

Date : August 18, 2020

“My own thinking has changed drastically from 35 years ago when I was taught to favor tangible assets and to shun businesses whose value depended largely upon economic Goodwill. This bias caused me to make many important business mistakes of omission”

– Warren Buffett, 1983 Investor Letter

“History never repeats itself but it rhymes.”

– Mark Twain (allegedly)

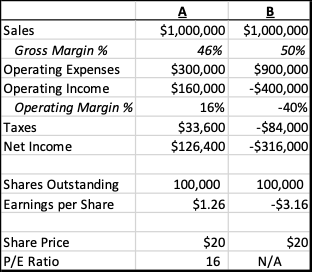

Imagine for a moment that you had a choice between investing in one of the following two businesses. They are in different industries with different business models but are forecasted to grow their revenues by the same amount into the foreseeable future and are both financed completely with equity. Which would you choose?

Figure 1: Hypothetical Income Statement

It seems obvious doesn’t it? They are the same size (judged by sales), both growing the same amount, have identical amounts of debt, but only one is profitable and yet they have the same valuation. Company B is clearly overvalued, right?

In fact, they are the same exact company.

The only difference between the two companies is how certain investments hit the income statement thanks to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). A simplistic explanation is that cash outlays for what is deemed a capital expenditure (a new factory for example) corporations can capitalize the costs and expense it over time via depreciation. For a company whose investments comprise of intellectual property and other intangible assets (say research and development for a pharmaceutical) the entire sum must be expensed immediately. That’s how you end up with two companies who invest the same amount of money ($600,000 in our hypothetical example above) but with vastly different impacts on the Income Statement. Company A capitalized the investment and depreciated it over 15 years with an annual expense of $40,000 (hence it’s lower Gross Margin %) whereas Company B has to expense $600,000 immediately because it is classified as R&D.

This isn’t due to any fault of the Financial Accounting Standards Board. Quite frankly I don’t envy having to make a uniform set of rules for all companies in this day and age. But it goes to show a further way in which the conventional understanding of what is considered “cheap” or a “value” investment is completely detached from economic reality. It also demonstrates an additional way in which relying upon P/E ratios to tell you anything about an investment’s prospects is delusional.

Let’s imagine another hypothetical. Imagine a company that owns a plant worth $5 million that steadily produces $1 million in annual profits. Let’s say it gets acquired for 10x its earnings, or $10 million. The acquirer would record on its balance sheet an asset worth $5 million for the plant and $5 million in “goodwill” for the excess it paid over book value to acquire the business. Under accounting rules, the acquirer would have to amortize goodwill over 40 years or $125,000 per year. Thus, earnings immediately take a hit and fall to $875,000 per year. At the same acquisition multiple, the business is now only worth $8.75 million despite no fundamental change in its economic viability. Is the business really worth ~13% less when nothing has changed other than who the owner is?

So why does this all matter?

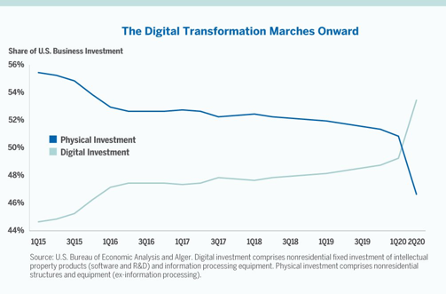

We’ve undergone a dramatic shift in the structure and nature in the U.S. corporate environment over the last 40 years. Around the time Buffett wrote his 1983 letter, approximately 80% of corporate value was captured via tangible assets. Today, the mirror image exists: 80% of corporate value is tied to intangible assets and for the first time, digital investment now exceeds physical investment (Figure 1). If the world is more comprised than ever of brand value, research & development, intellectual property, trademarks, and other forms of intangible assets, should we really be using the same barometers?

Figure 2: Digital Investment Exceeds Physical Investment for the First Time

Buffett understood earlier than most that GAAP’s accounting umbrella masked value that would translate to future growth. Brands (such as Coca-Cola, Gillette, and Guinness which Buffett bought in the years following this letter) possessed powerful “economic goodwill” that allowed for steady growth thanks to their consumer value that did not exist on financial statements anywhere. Rather than stick with the rigidity of his priors, Buffett adapted. The markets, en masse, would follow eventually. Just like they did in the case of Adobe in the 2010, Amazon in the 2000s, and Tele-Communications Inc (TCI) throughout the 1970s and 1980s. All utilized new business models that irked traditional income-statement oriented investors but rewarded those focused on the ultimate measure of intrinsic value: future cash flow.

I can’t help but think there’s a much larger lesson to learn from Buffett’s letter (arguably, the most extraordinary of his entire career) that should be extrapolated more generally. Buffett didn’t deviate from first principles, he just realized the shortcomings of the old ways of thinking. As Keynes remarked, and Buffett quotes in the same letter, “The difficulty lies not in the new ideas, but in escaping the old ones.”

Earnings always mattered, but where you looked for undiscovered value was primarily considered to be on the balance sheet for decades. The reason why is because Buffett’s teacher and the father of value investing, Benjamin Graham, developed his investing philosophy with mental and psychological roots framed by the Great Depression. In the context of the Depression a philosophy of conservatism and retaining capital makes all the sense in the world. It wasn’t wrong to look for value on the balance sheet; it simply wasn’t exclusive and treating it as such led to sins of omission. If earnings (and cash flow) are what matters, who cares if it comes from a tangible or intangible asset?

Similarly, I couldn’t help but think there are other ways in which investors, economists, market commentators, etc. have framed their thinking in worlds of the past and haven’t adapted to changes since.

We are all slaves to our experiences.

Take the transmission mechanism of monetary policy for example. To people who grew up and were educated during the inflationary 1970s and 1980s (ie the vast majority of policy makers and professional economists today) their sole understanding of money supply and credit growth comes from monetary policy. Yet, during their formative years the repo markets were just being born. Today, the repo market is responsible for over $3 trillion of credit each day. Could you imagine having a mental model of credit growth today and not including the repo market or collateral chains or shadow banks? And then basing policy of such outdated thinking? Yet none of these institutions nor their impact on the economy existed ~40 years ago.

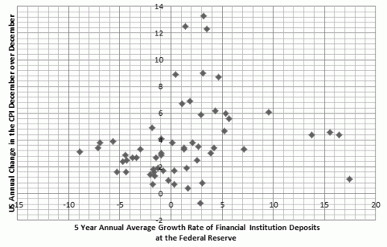

The same goes for what explains inflation. Show them evidence that base money has no relationship with the price level (Figure 2) and instead of adapting, they’d rather cling to their narratives. It’s not to say that inflationary pressures don’t exist in general, or that it doesn’t potentially threaten long term competitiveness but rather that looking for it in one single place is the proverbial square peg in a round hole. Stupidity after all is doing the same thing time after time and expecting different results.

Figure 3: The Relationship Between Base Money and Inflation Doesn’t Exist (Peter Stella)

Or take into consideration a desire to constrain the largest tech companies going forward. There are arguments for and against such measures but the ones coming from those with the authority to do anything about it are short on logic and understanding how tech works. So long as regulation is based upon a consumer welfare doctrine it’s a legally perilous endeavor to banish something that consumers openly choose. Further, without an understanding or proper accounting of network effects and zero marginal costs, regulatory efforts will largely miss the point: the largest companies have come to existence not from constraining supply, as the titans of the 19th century did, but by aggregating demand via choice. Using a blunt, 20th century analog tool on 21st century digital business models could end up failing or inadvertently enhancing their leverage and standing. One need to look no further than the viability of the tobacco industry. Prior to regulation the business was by in large a terrible place to invest. Enter regulation and the ominous curse of unintended consequences took hold: tobacco has been the best place to be for decades thanks to no new entrants (and thus a limited need to advertise) and enormous pricing power.

The 21st century version of unintended consequences could have profound effects on how information flows going forward and the ability to hold entrenched interests to account. Ask yourself, how and why did every single major media organization and government agency (save Taiwan) get the connections between COVID-19, transmission rates, and masks wrong for so long? How did it change? (Hint: the answer rhymes with fwitter). The funny thing about zero distribution costs is that it not only enables those with a value proposition to develop network effects, it also allows single independent actors to co-opt the system, gain prominence and challenge conventional “wisdom” (like say whether or not an asymptomatic person can transmit a virus). In a complex, biological system the way to find a signal is by increasing and strengthening feedback loops, not diminishing them.

Value investing never was and never will be about what looks optically cheap. It’s about finding a dollar trading for 50 cents. Where we find it is not relevant but to give ourselves as many bites at the apple we need as many tools and mental models as possible. Transitions and changes in life require renewals of principles rather than revolutions. More broadly, we’re not married to the means but while truth is timeless the way it manifests is not.

In the words of General Shinseki, “If you don’t like change, you’ll like irrelevance even less.”