What Does the Market Expect for Dividends?

What Does the Market Expect for Dividends?

-

Author : The BlackSummit Team

Date : December 22, 2020

“We have made very little progress in life by trying to outguess these macroeconomic factors. We basically have abdicated. We’re just swimming all the time, and we let the tide take care of itself…. The trouble with making all these economic pronouncements is that people gradually get so they think they know something. It’s much better just to say, ‘I’m ignorant.'” — Charlie Munger

I’ve gradually become either more disillusioned or disinterested in macroeconomic forecasts and the top-down style of investing that usually flows out of them. I find that these forecasts tend to thread a needle between being just vague enough that projections can rationalize triumph in hindsight but be obscure and obtuse enough that they’re effectively useless when it comes to making allocation decisions. A grand theory of everything may be convenient but it’s rarely accurate. Investing is a hard enough game as it is and of course every purchase or sale of a security implies some embedded forecast. Why anyone would want to layer on top of those challenges the multiple, compounding, interconnected dimensions associated with macro or top-down variables is beyond me. Not to mention, most of those projections about economic growth, unemployment, inflation, interest rates, etc. rarely, if ever, take any direct consideration of valuations. Further, security prices and macroeconomic variables can often diverge in two starkly different directions. 2018 gave us a wonderful economy and down year in the markets while 2020 has seen all-time highs with some of the ugliest economic data points in human history, not to mention nearly 2 million tragic deaths from COVID-19.

And yet despite that, thanks to temptation or some other factor, I find myself with a macro bet as one of the most intriguing opportunities in the market today. The following is why.

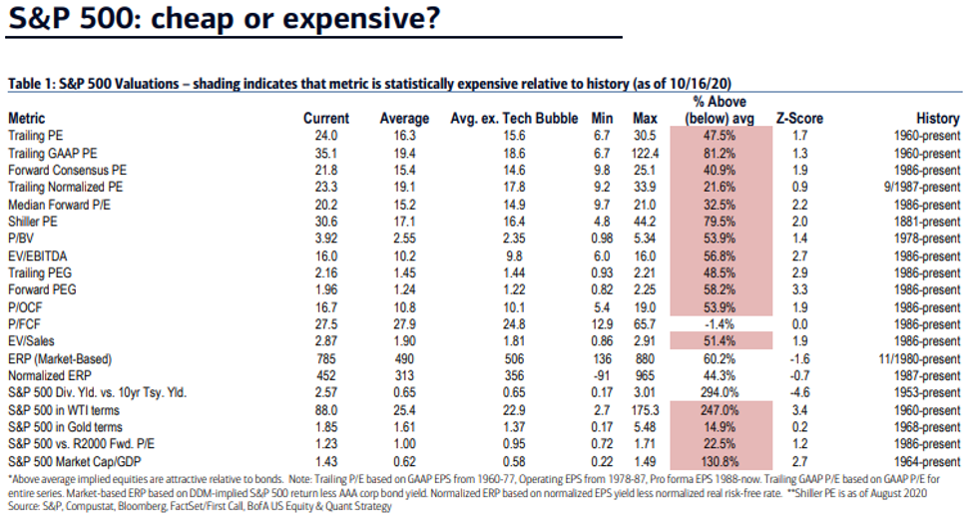

First, while I try and steer away from broad brushed market wide valuation metrics, I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that valuations currently embed a lot of optimism (Figure 1). When so many metrics point to excessive valuations you can’t help but take notice. Even my preferred metric of Free Cash Flow Yield sits at average levels, but of course looks backwards instead of forwards. Short-term measures of valuation are not great timing mechanisms of course and markets can always stay elevated longer than investors anticipate. But even long-term measures do not make me sanguine. While whether the market is “overvalued”, a somewhat subjective designation, can be debated, I find it hard to say that it is a bargain.

Figure 1: The Market’s Valuation is Elevated Across A Number of Measures, Bank of America

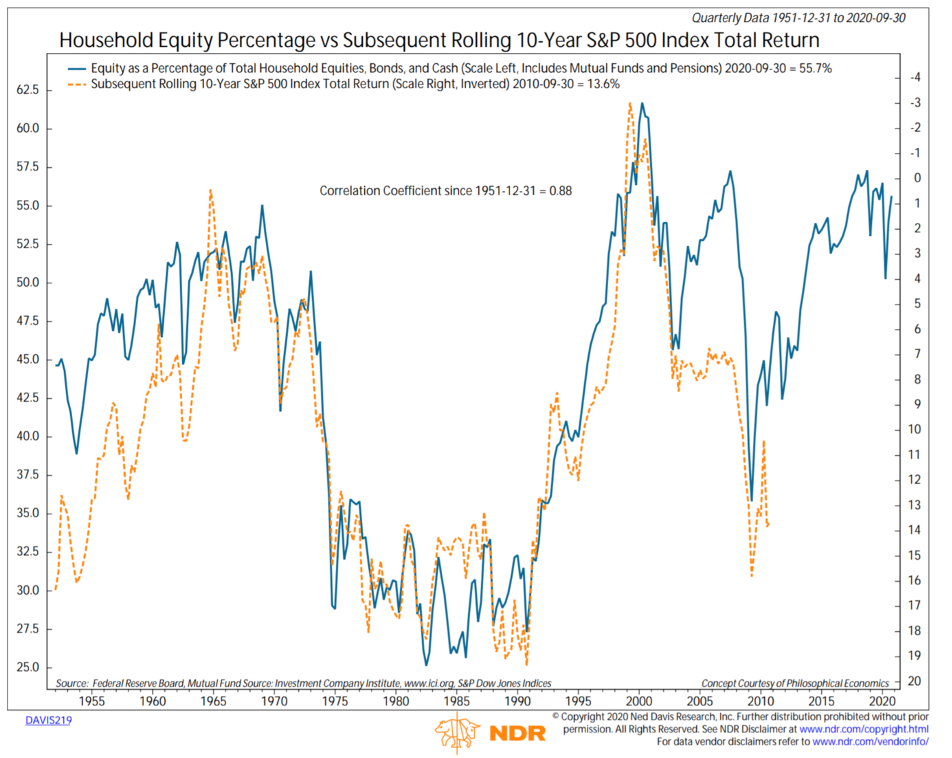

Figure 2: Long Term Returns From Here are Not Promising, Ned Davis

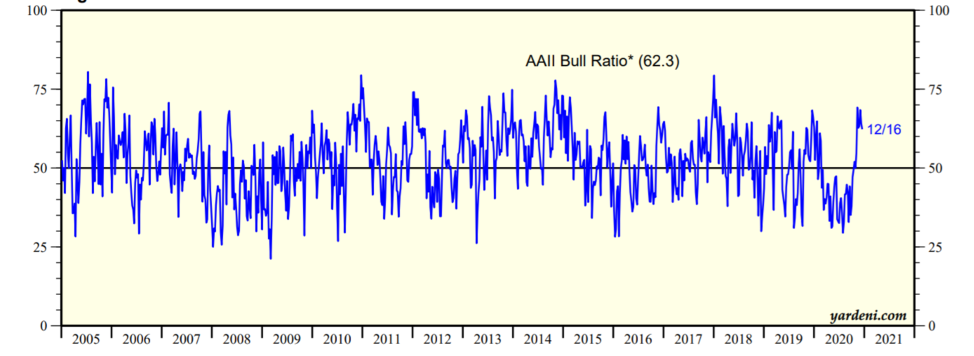

Second, sentiment is finally catching up to the market that the crowd now seems to be on the side of the market moving higher in the immediate term. The crowd can be right but consensus is not a side I like to sit alongside with.

Figure 3: Nothing Changes Sentiment Like Price

Third, catalysts to take the market higher or lower are easy to come by right now. Fiscal stimulus is far more potent by nature than anything monetary institutions can offer and there is plenty left that hasn’t been spent down from 2020’s measures in addition to the ~$900B passed this week. Corporate profits could easily move higher as a result. In addition, it’s not unreasonable to theorize that the economy will now organically grow off of the higher base provided by government and monetary support, and may do so in a more productive and efficient manner thanks to the rapid adoption of digital tools and services. Relatedly, the transition in dozens of industries inspired by the COVID pandemic is making the future winners more profitable and more apparent, partially explaining wide valuation divergences seen in the market.

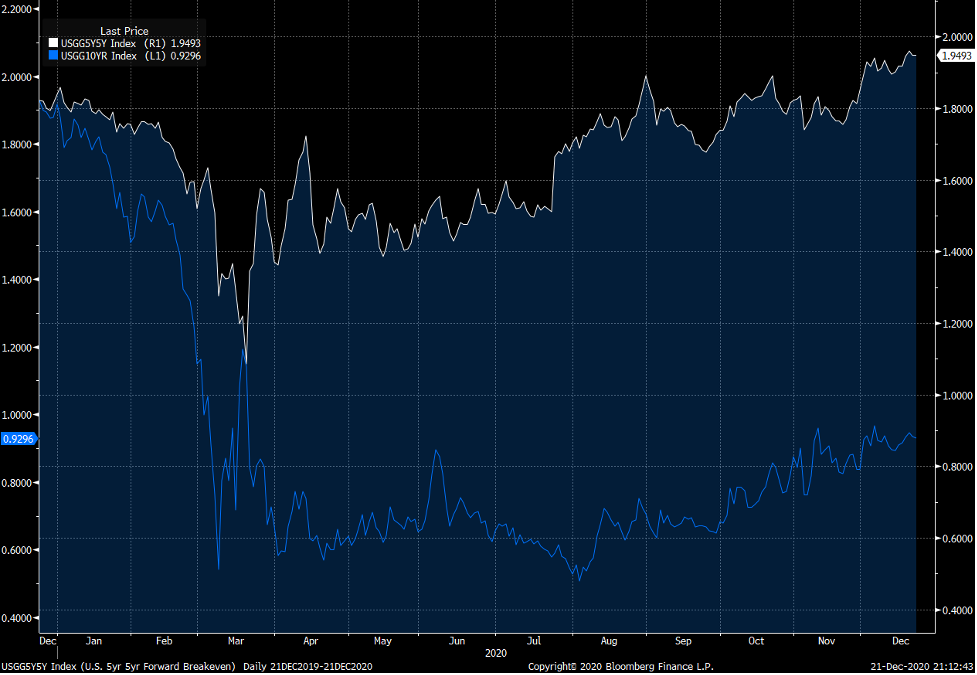

At the other end, the market has had numerous opportunities to discount the magnitude and impact of any fiscal stimulus. The demand picture, even with stimulus, is extremely uncertain as COVID cases rise globally, vaccine rollouts struggle with logistics, supply chains are extremely tight, and budgets for spending and investing are paused. This all while the unemployment picture has currently slowed its improvements. Not to mention the possibility that if things go well, rates have plenty of room to catch up to inflation expectations that could scare investors or draw capital out of equity markets.

Figure 4: Inflation Expectations (White) vs 10 Year Rates (Blue)

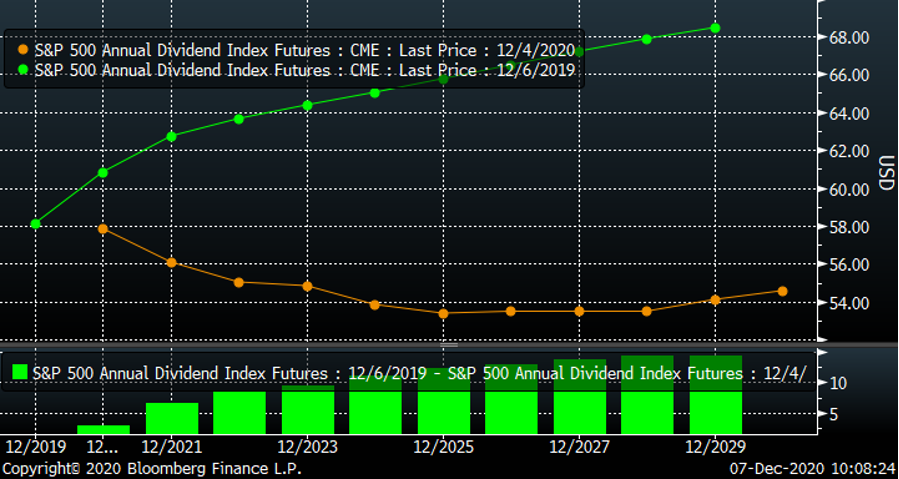

Which brings me to what I see as the most compelling opportunity today: dividend futures. Much like buying a futures contract on the S&P allows you to get exposure to the market today via a future position, dividend futures entitle the buyer to receiver dividends paid out by index constituents at a future date. The opportunity is presented clearly in Figure 5: dividend futures are in backwardation until 2029. While in 2019 the S&P 500 constituents paid out dividends equivalent to $58 per share the market doesn’t anticipate that dividends will get back to that level at any time in the foreseeable future. But most surprising is that the futures market is pricing in further cuts to dividends in 2021 and 2022 to what has already transpired this year. This despite the fact that both the economy and corporate profits should grow beyond 2020 levels.

Figure 5: Dividend Futures Are Backwardated Until 2029

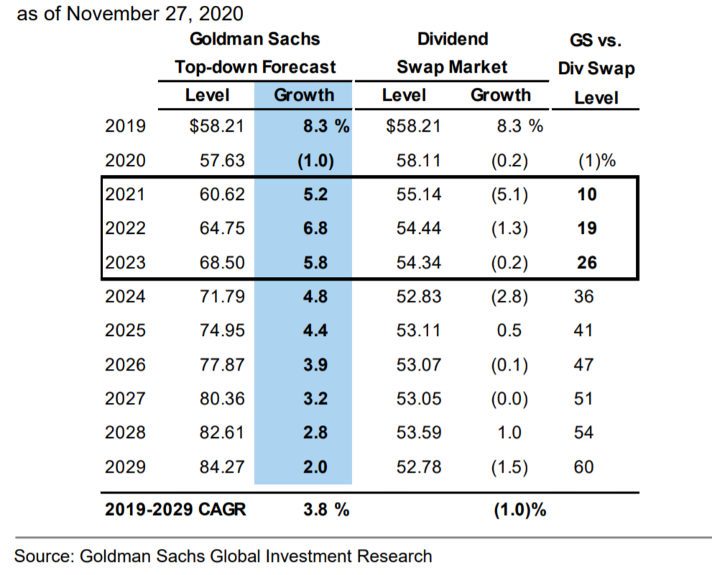

Dividends were understandably cut this year as companies prioritized liquidity above capital returns and some industries, those exposed to travel for example, may not pay anything in 2021. But plenty of companies, including ones reliant on improving growth, have resumed paying dividends and increased payouts. Mobil, Darden Restaurants, and Estee Lauder are just a few. Yet, the market’s expectations and conservative assumptions still provide a healthy return opportunity according to Goldman Sachs (Figure 6). Other factors such as corporate tax rate changes don’t meaningfully change the opportunity. Even a scenario whereby energy firms cut dividends by 50%, due to low oil prices, and others return to 2019 returns lends a scenario where Dividends per Share come in around $57. And that doesn’t allow for any growth in any other parts of the market or the restoration of dividends from those who suspended them, like banks, who are responsible for more than 13% of S&P dividends alone.

Figure 6: Wide Divergences Between Dividend Estimates and Market Pricing, Goldman Sachs

The advantage of the opportunity is that it allows investors to take part in continued economic and profit growth, through equity exposure, without the valuation risks cited above. There is no implied valuation in the product. Whatever level Dividends per Share will be the final value of the futures contract. If they come in above current market pricing then investors will profit. If they don’t however, losses will occur. However, a market scenario whereby dividends fall more than 5% in 2021 from very low 2020 levels strikes me as a disaster for equities and risk assets. Moreover, dividend futures don’t demonstrate near as much volatility as other equity products.

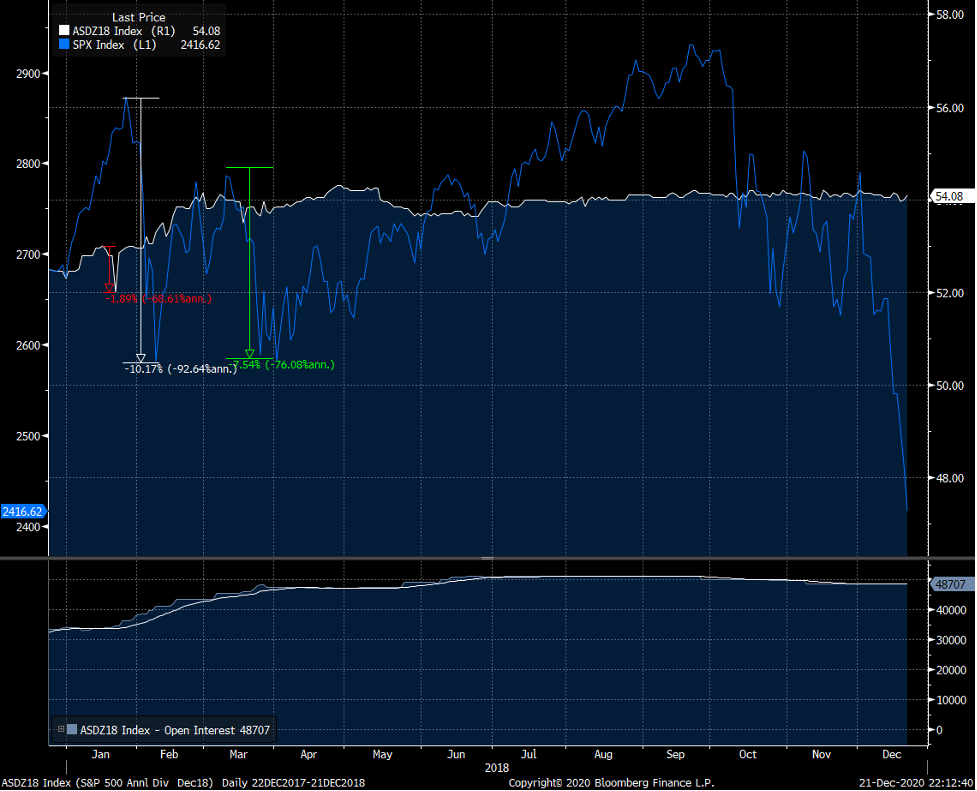

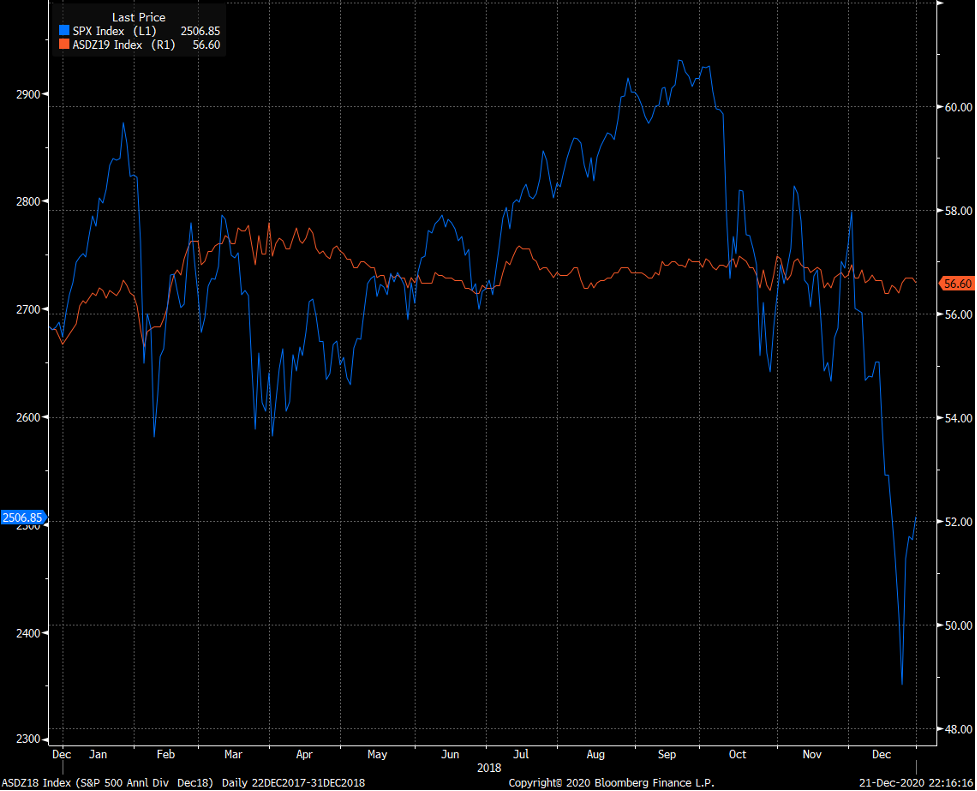

Take for example the 2018 contract. When the market corrected by 10% for no reason in February 2018 the Dividend Future contract for that year fell less than 2%. An additional 7% sell-off a few months later didn’t even register for the dividends to be paid out. Neither did the disastrous fourth quarter of that year. In fact, not even 2019 dividends were jeopardized.

Figure 7: 2018 Dividend Futures (White) Didn’t Flinch Amidst Market Volatility (Blue)

Figure 8: Neither Did 2019 Dividends (Orange)

No investment is without risks. Tax rates may change in a manner more punitive than anyone forecasts, unfavorable debt markets may emerge and tighten the ability for firms to return capital, liquidity in Dividend Futures is still young, and other exogenous factors can all emerge. However, I have a tough time imagining a market that succumbs to one or more of those conditions that doesn’t impact the equity impacts more broadly in a much more damaging manner. The upside may not be as high but with much better downside protection and some evidence of mispricing it’s a tradeoff worth making in my opinion.