This Is Not Your Forefather’s Treasury Market

This Is Not Your Forefather’s Treasury Market

-

Author : Joel Charalambakis

Date : December 21, 2021

US CPI has come in hotter than most of the worrisome projections

warned about, reaching the highest levels the economy has seen since

the stagflation of the 1970s. The Federal Reserve has announced both

a start to the tapering of asset purchases, as well as an acceleration in

their schedule so that bond buying will be finished within the next few

months. They’ve also openly stated that some of the inflationary

pressures being experienced may not be so transitory after all. The

most recent series of projections from the Federal Reserve Board estimates 3 rate hikes over the coming 12 months. Real GDP forecasts are currently projecting growth of nearly 4% for 2022, on the back of healthy consumer spending and resurgent capital investment.

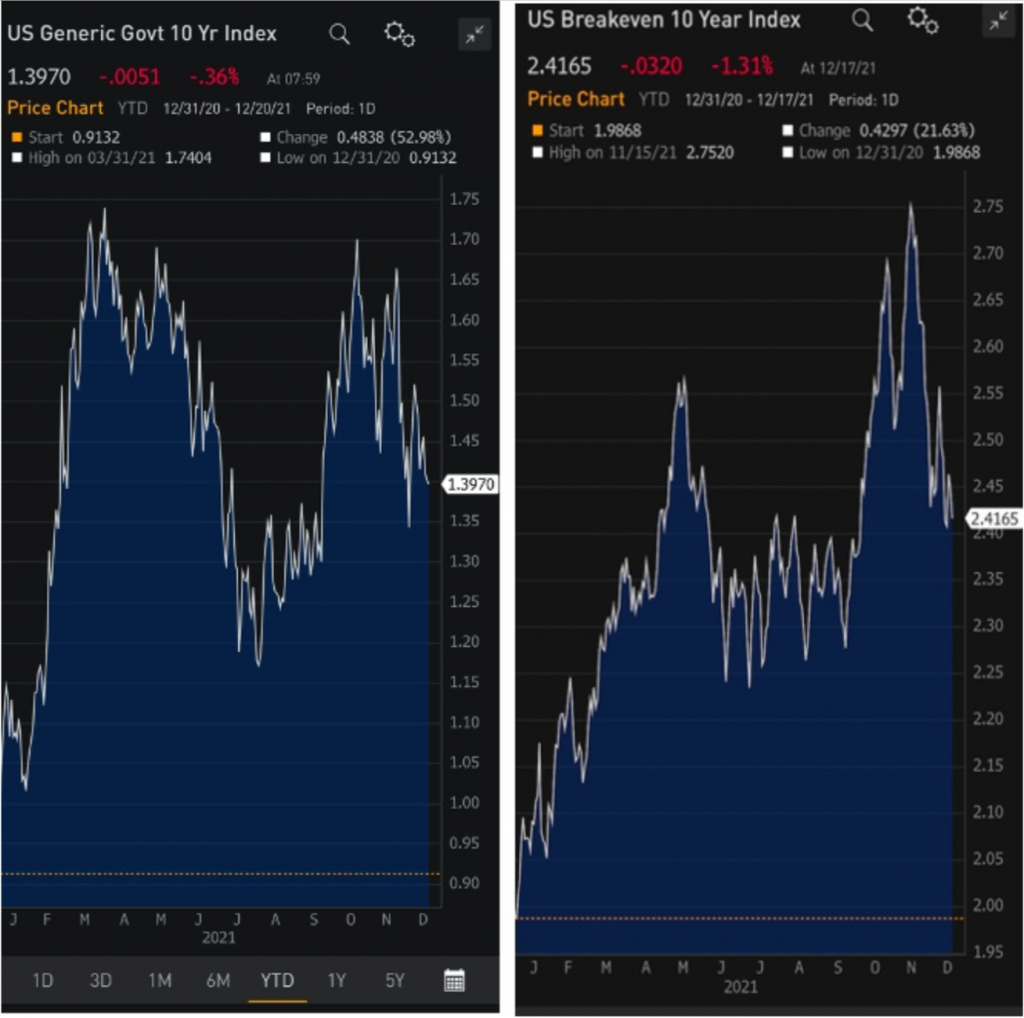

And yet, despite all of that, interest rates could not care less. Rates resumed higher after their summer low sparked by investors being caught offsides into the June Fed meeting but have since come down in a manner similar to this summer. Breakeven rates, which infer forecasted levels of inflation between different treasury securities, also collapsed in recent weeks across every term examined.

The move in rates defies every academic understanding of the drivers of bonds and the Treasury market and runs counter to the experiences of traders and investors accustomed to substantially higher levels of both rates and long-run inflation levels.

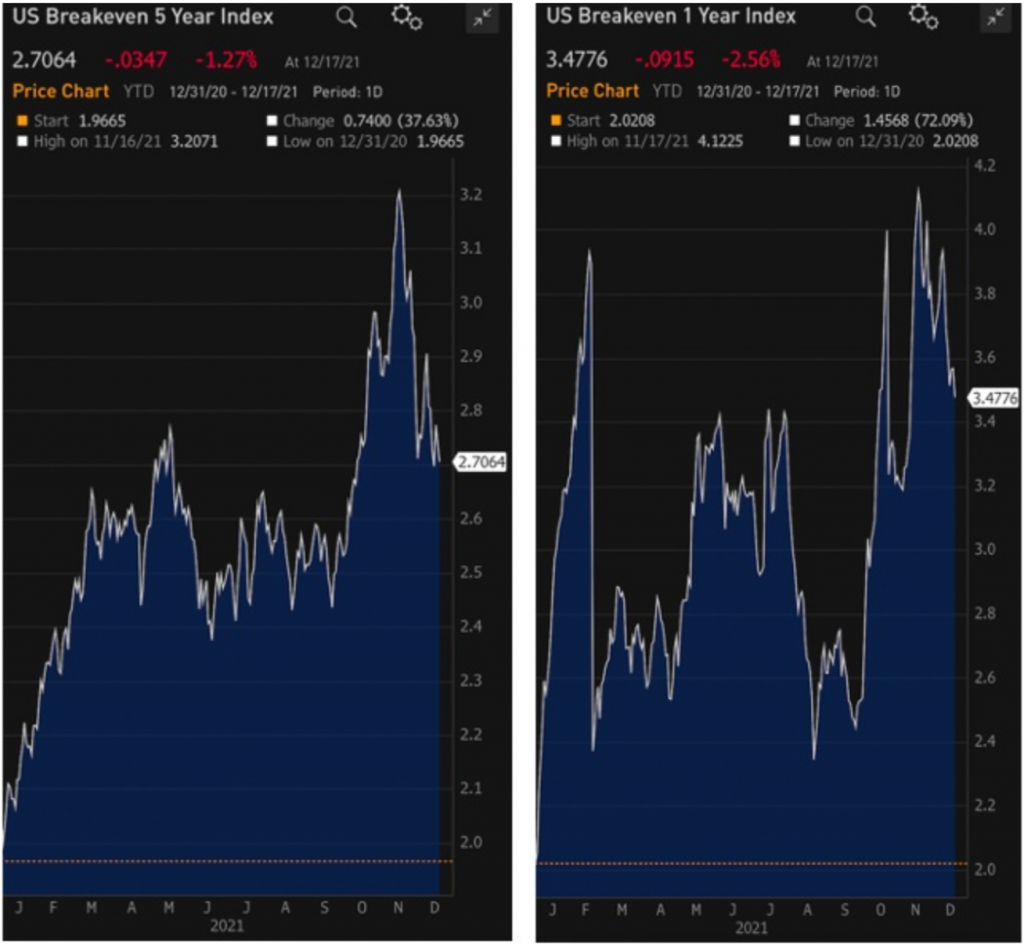

Yet one under-discussed fact is that who the buyers of Treasuries are now compared to generations ago are quite different and with different motivations. The tri-party repo market, which currently sees volumes over $4 Trillion each day, did not even exist in the heyday of stagflation while bilateral repurchase agreements were miniscule.

Figure 1: The Repo Market: Then and Now, NY Fed

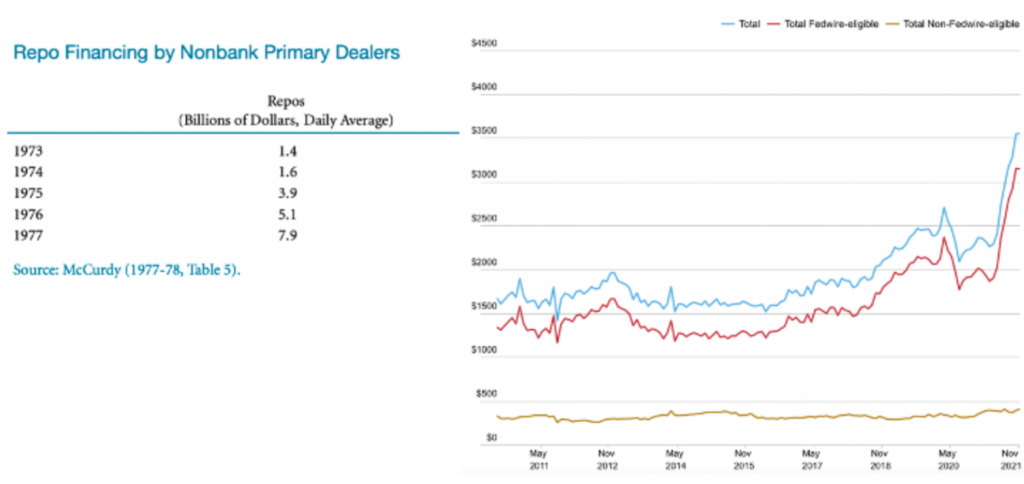

The birth of the tri-party repo market in the 1980s and its evolution after the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997 and regulatory changes of the 2000s changed the character of the economy’s credit channel. Prior to, and in the early stages of its existence, the relationship between credit creation and monetary policy, which operated exclusively at the short-end of the curve, was direct. But the growth of the repo markets over the last few decades implicitly means that Treasury issuance is increasingly a money market issue, and thus an issue for monetary policy, as explained here; the increased reliance on funding the economy via Treasury collateral has occurred simultaneously with a deviation in the relationship between rates on the short-end of the curve and the long-end. Ultimately, the relationship we’re all used to in “normal times” between monetary policy and the short-end of the curve is gone thanks to the repo-centric structure of our markets.

Figure 2: Pre-Repo, The Short and Long End Moved Together

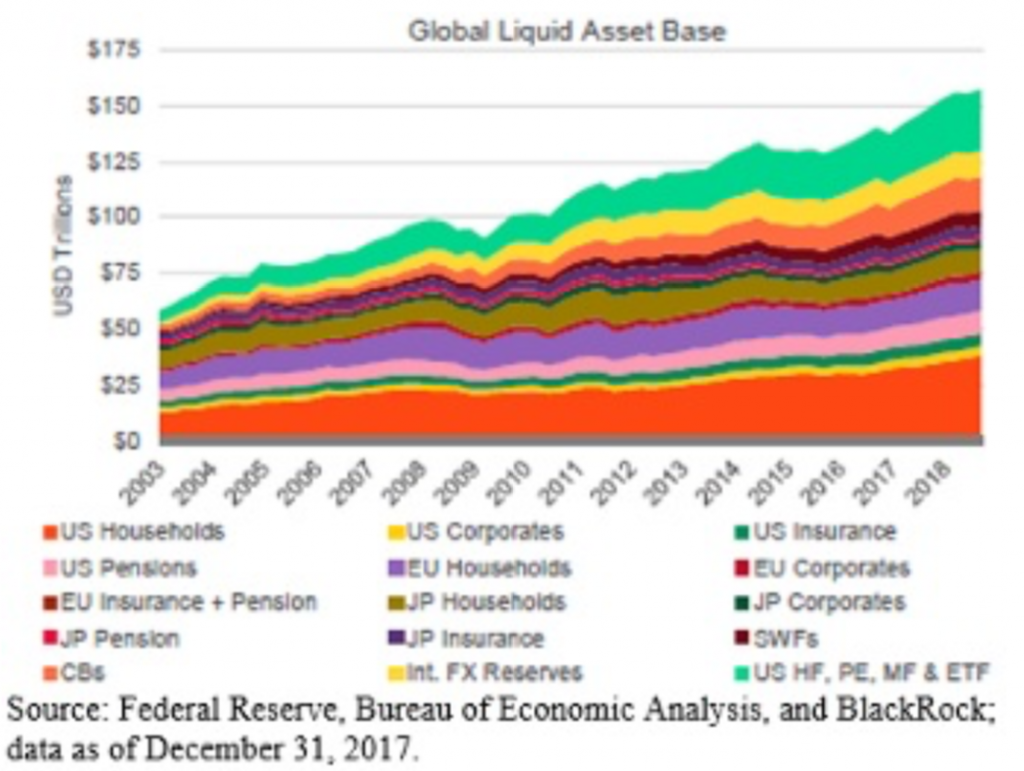

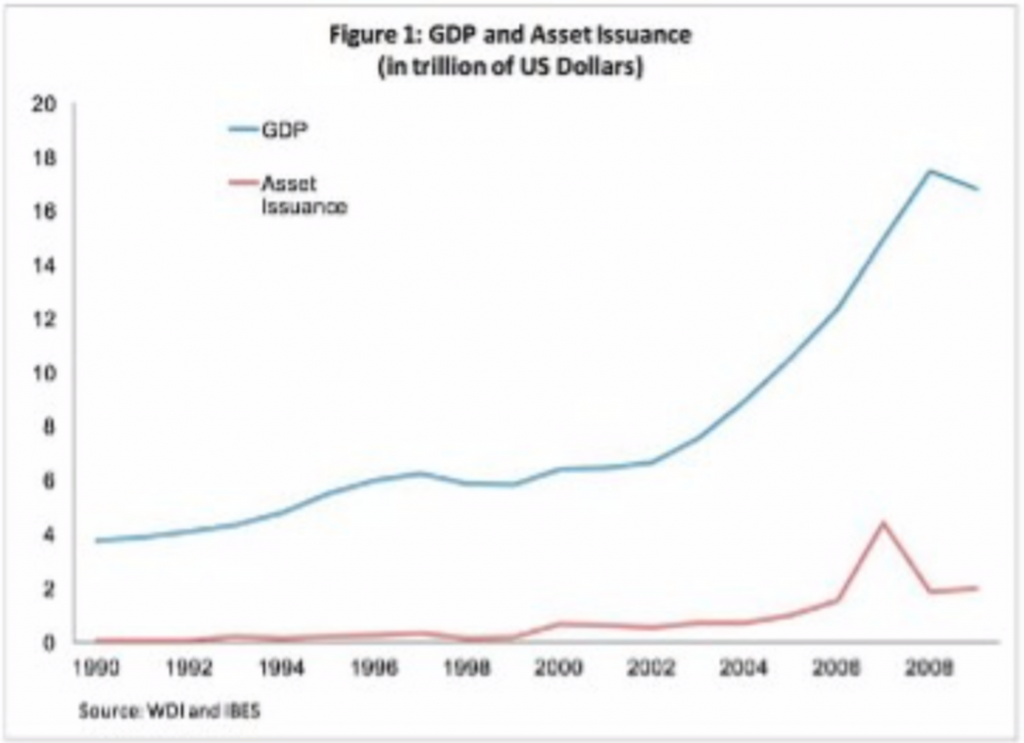

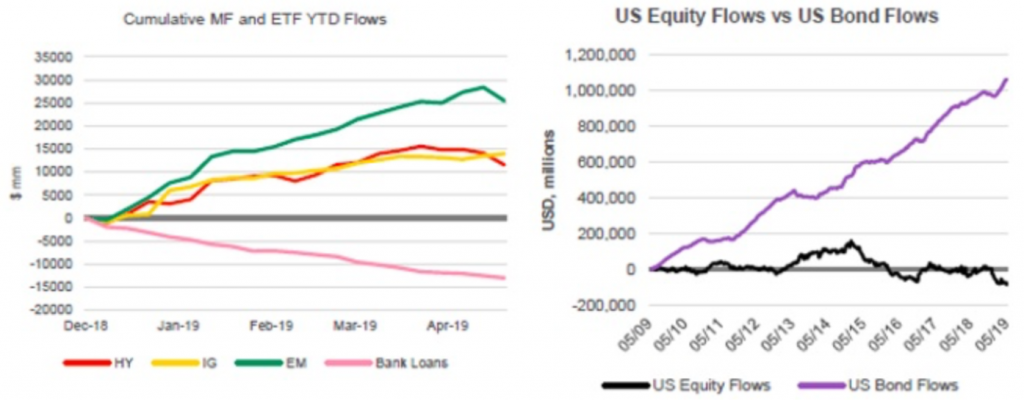

Simultaneously the global asset base has exploded over the same time period, rising over 200% and needing a home (Figure 3). Much of the increase has come from a boom in capital in Emerging Markets. Yet, their own financial deepening has significantly lagged behind its growth in GDP per capita (Figure 4). Lacking adequate safe assets at home, capital was sent overseas. It did not end up in the equity markets but rather Treasuries (note how equity flows were negative for the decade post-GFC…so much for the QE driving equity prices up narrative).

Figure 3: The Global Asset Base Has Tripled, Blackrock

Figure 4: EM Financial Markets Have Lagged the Development of their Broader Economies, Alex Barrow

Figure 5: Foreign Capital Went to Treasuries, Not Equities, Blackrock

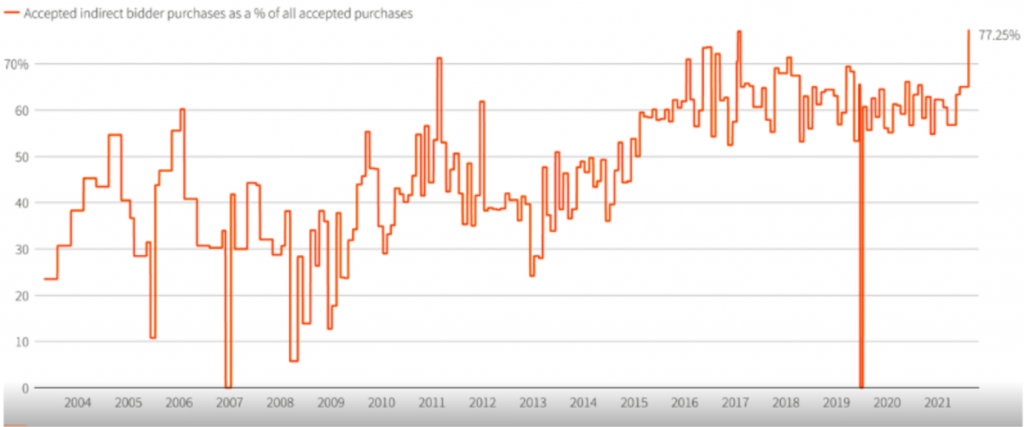

If there’s a bid underneath the Treasury market it’s more likely than not coming from foreign capital. Demand from foreign bidders at Treasury auctions hit an all-time high this year.

Figure 6: Foreigners Are Buying Treasuries at a Record Rate

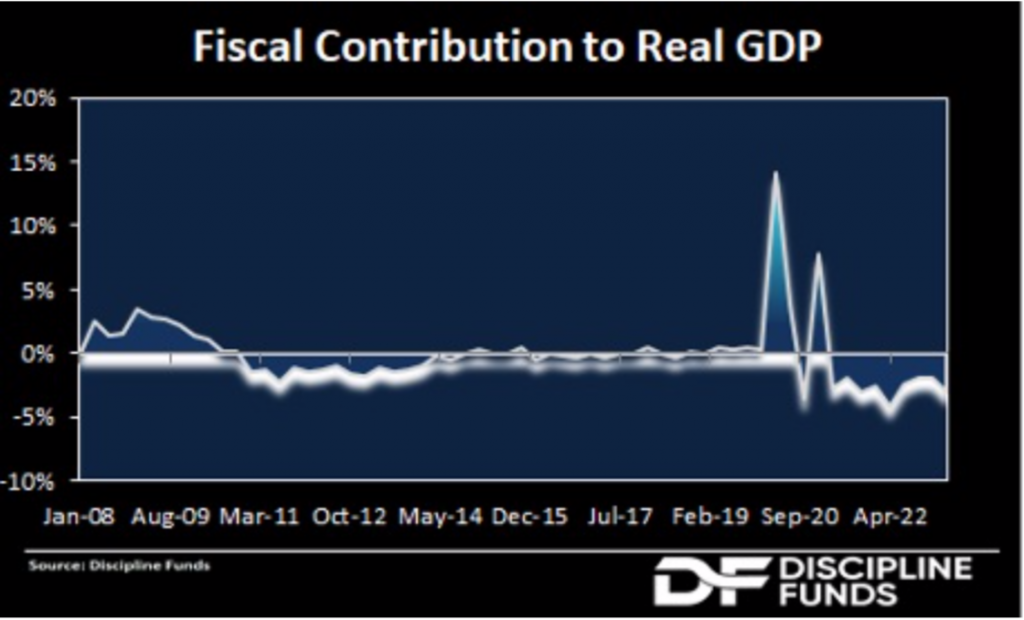

Going into 2022 however there will be even fewer bonds available given the expiration of multiple fiscal efforts to combat the consequences of the pandemic (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Fiscal Headwinds Mean Less Treasury Supply, Cullen Roche

Even a balance sheet run off by the Fed (which hasn’t been announced yet) may not be enough to satiate the everyday appetite we have from the forces discussed above. If investors have, understandably, been surprised at the direction of moves by interest rates in recent weeks, they may be set up for an even greater surprise next year.