Some Thoughts on Inflation

Some Thoughts on Inflation

-

Author : Joel Charalambakis

Date : April 13, 2021

“The cure for high prices, is high prices.”

Inflation has probably been the most debated and discussed macroeconomic variable of the past year. It’s been hotly discussed for much of the past decade as hysteria over QE/unconventional monetary policy has absorbed more investor attention than deserved. For all the ink spilled on QE the consequences of rising inflation, and even potentially hyperinflation, in the US was both the most popular forecast and also fantastically wrong1. The chatter has only accelerated over the last year as an all-hands-on-deck approach to combating the impact COVID-19 on the economy forced the hands of both monetary and fiscal forces.

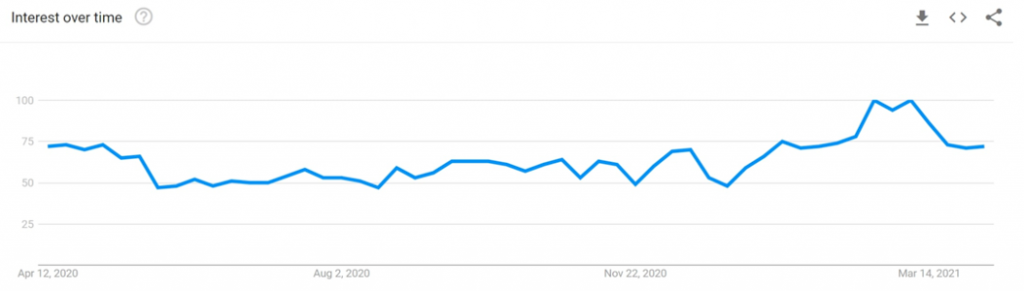

Figure 1: Interest in Inflation Has Increased, Especially Around the Fiscal Packages

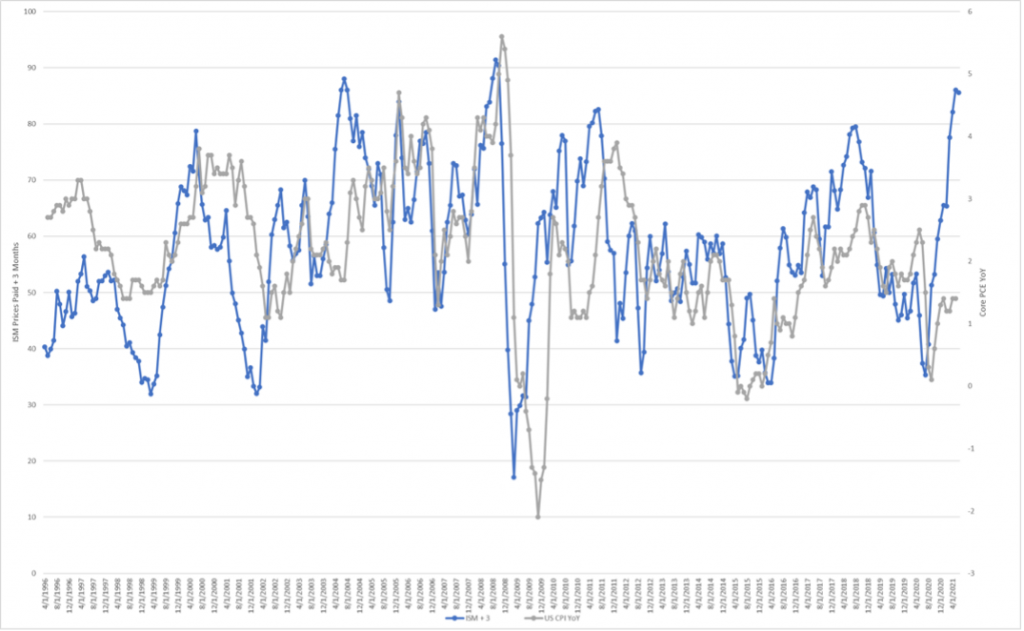

You’re starting to see some of the pricing pressures materialize in macro wide indicators like the Prices Paid component of the ISM Index. On a 3 month-lag, Prices Paid has a noticeable, but not perfect, relationship with CPI (Figure 2). The most recent results from the ISM report suggest some CPI numbers coming in the next few months that we haven’t seen in years.

Figure 2: ISM Prices Paid (Blue, Left Axis) vs CPI YoY (Gray, Right Axis)

What’s “different” this time is that unlike QE, fiscal stimulus actually puts money into the real economy. The former is simply an asset swap from a bank’s perspective; the Fed takes one low-return asset (a bond) and swaps it for an even lower return asset (reserves). There are no new financial assets created, but instead simply a change in their composition. It’s why money supply growth post-GFC is remarkably similar to pre-GFC. The latter at 6.1% average yearly growth and the former 6.3%. In contrast, rising fiscal deficits means the issuance of new financial assets and the cash proceeds end up in the hands of individuals. Eventually, those dollars get spent and hit Corporate America’s bottom line. The scale of the fiscal effort this time is unprecedented and even compared to the efforts post-GFC the fiscal stimulus is multiples of that historic effort and in a compressed timespan.

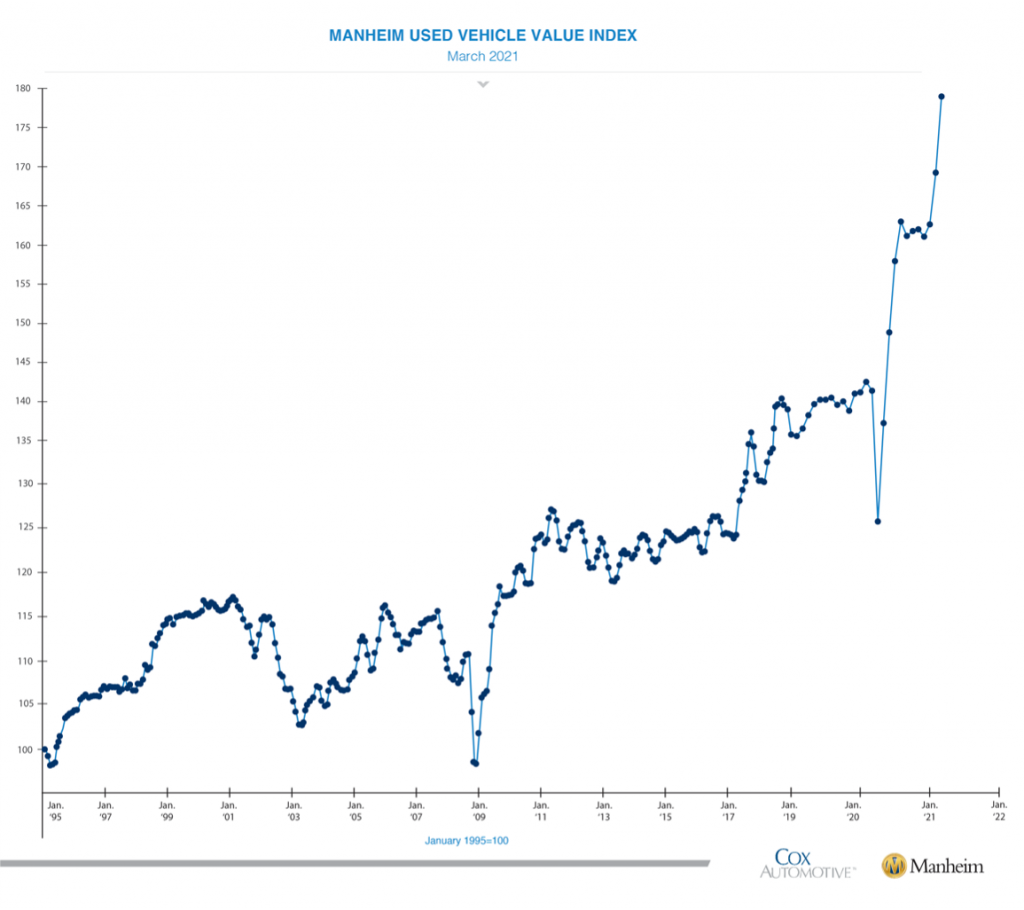

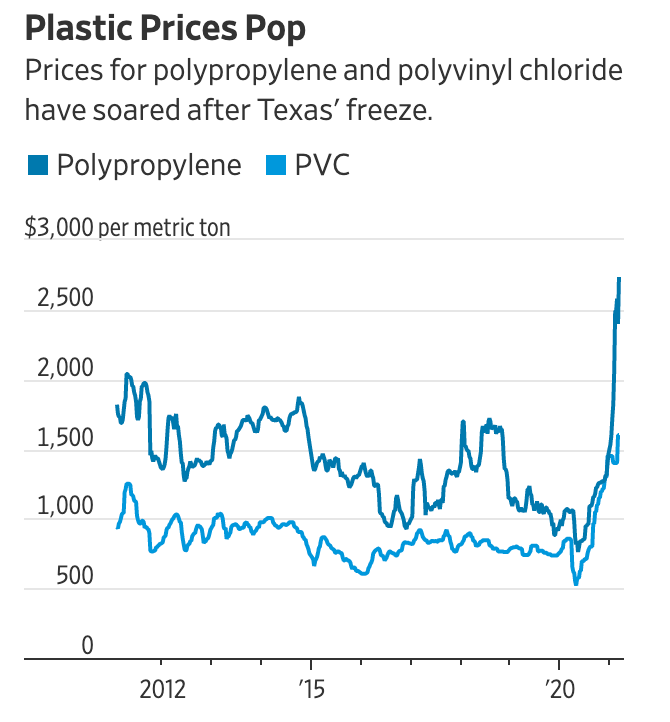

Inflation pressures are building from both the demand and supply side. Markets like housing pulled forward demand that analysts have been waiting on for several years resulting in some of the strongest price increases since the Financial Crisis and should continue over the next year or two. Autos have seen spikes of demand as commutes will get longer but also due to supply chain issues while the fastest economic growth in decades is putting upward pressure on commodities and intermediate inputs like energy and plastics.

Figure 3: Home, Used Car and Plastics Price Appreciation

My personal suspicion is that over the rest of 2021 we’ll witness inflation numbers much higher than what we’ve been accustomed to. Base effects from last year will amplify the headline figures but the size of the fiscal efforts will trounce any sort of denominator effect.

The implication of inflation on investors is not straightforward however. Common logic would suggest that with higher inflation interest rates must rise, pressuring equities via lower multiples and eventually functioning as a brake on economic growth. It’s a compelling and intuitive argument. With multiples above historical means, and interest rates still painfully low, some people rush to some pretty dire circumstances for risk assets. They point to the acceleration in the 10 year so far in 2021 and the correction in the Nasdaq as evidence that stocks are fragile to higher rates. That’s too simplistic in my mind and the broader causation narrative strikes me as more random than anything. Multiples throughout the 90s and 2000s were just as high if not higher with worse earnings growth and the Fed Funds rates over 5%. Never mind the fact that rates haven’t budged while the Nasdaq has rallied to set new all-time highs since their correction in February. Further, this school of thought assumes higher inflation, and thus higher rates, are a multi-year phenomenon. While I do expect inflation considerably higher in 2021 and probably in 2022 the long-run trend has every chance of reverting back to its post-GFC mean. Whether inflation is higher forever remains to be seen.

As for assessing the intrinsic value of an individual security I don’t see the impact from inflation on valuation as anything to be concerned about. I don’t know of anyone who constantly changes their discounted projections of earnings or cash flows with every shift in the yield curve. And I certainly don’t know of anyone whose assessment of any stock is dependent upon a discount rate of 2%; underwriting any investment at that kind of level is asking for trouble. That doesn’t mean that a more responsible discount level protects an investor’s capital however. Stocks are still prone to market cycles and sentiment shifts.

The longer-term concern in my opinion that investors should be on the lookout for is the (remote) possibility, that we’ve entered a new policy paradigm. For roughly 40 years we’ve been fed this idea that lower taxes and monetary policy were the only combination needed to govern the economy. The results have been anything but stellar with two massive bubbles and an entire lost decade of economic progress. Promised tax cuts in the early 2000s and late 2010s did nothing to accelerate growth or investment while monetary policy’s toolbox looks increasingly dull. It’s not hard to paint a scenario whereby fiscal authorities look back upon the growth that will come in 2021 and seek to make targeted fiscal boosts a more permanent policy fixture. What the implications would be on inflation and rates is complete conjecture I don’t think a very different fiscal agent from the one we’ve seen over the last few decades can be ruled out.

Notes

- For the record, no, we didn’t get the inflation “showing up in asset prices” instead of the real economy as far too many people say. Since the end of 2009 corporate America got a very real ~10.5% earnings growth per year off a 13x PE multiple and the highest levels of Return on Invested Capital for the median firm we’ve seen. Raising the multiple to 17x, very much in line with historical averages, with that growth gets you to the 13% per year the S&P 500 did between the Financial Crisis and COVID. If you think an average multiple and double digits earnings growth constitutes asset price inflation, we’ll just have to agree to disagree. Moreover, for the Fed’s balance sheet to expand by 700% since the GFC and for multiples only to slightly exceed their long-run average doesn’t exactly inspire a lot of confidence in those who treat the Fed with omnipotence.