The original iPhone, announced in January of 2007 and released in June of that year, was greeted with plenty of skepticism. Smartphones weren’t entirely brand new, even ones with touch screens, so it wasn’t easily foreseen what an outsider like Apple could provide. The critiques, of the device and the company, were numerous: Larger companies, like Blackberry and Nokia, had far more experience putting together a phone and the myriad of parts and components that went into them from very long supply chains. Nokia controlled over 40% of the market at the time Apple released the inaugural device. Blackberry had an extremely loyal user base, particularly of corporate customers. The battery didn’t last a day while some models already on the market lasted up to a week. The glass front was susceptible to being cracked if dropped. It lacked a physical keyboard. And this was all happening on a device that would be priced at the top of the market. Some CEOs thought there was no chance they’d get any meaningful share.

There’s an old anecdote about the way Wall St. analysts were evaluating Apple post the release of the iPhone that has always stuck in my mind. Apple’s stock would rise 130% from the time of Steve Jobs’ announcement of the phone until the end of the year. The move befuddled analysts. One ran some math to unequivocally show how Apple was wildly overvalued. He argued that if you took the total size of the entire phone market, gave Apple 100% share with industry-leading margins, and a premium multiple, the stock was still overvalued.

Apple’s market cap during that first year of the iPhone peaked at ~$175B; its sales of iPhones over the last 12 months exceed that figure. Today it’s the world’s most valuable company at $2.8T.

Now no one should be mocked or ridiculed for not seeing the full extent of Apple’s rise; such success is beyond anyone’s imagination, especially over that length of time. Some of the skepticism was perfectly rational, but the anecdote still provides some lessons and an example of investors and other financial professionals being so rigid, mechanistic, and linear in their thinking that they end up fighting the last war. In the case of Apple and the iPhone, this analyst, and many others, were trying to fit a square peg in a round hole; by only thinking of the product as a phone they couldn’t see the differentiation. By failing to expand their understanding of what a phone was or the jobs to be done, their analysis was myopic. They missed the forest for the trees.

The area that probably struggles with fighting the last war the most is regulation. No two crises are ever the exact same; they may have commonalities like the use of leverage or greed or stupidity, but how they play out is never identical. Take the recent banking panic and the demise of Silicon Valley Bank as an example. Regulators spent the post-GFC era zeroing in on credit and liquidity risk exposure of banks and failed to consider interest rate risk. On the other side of the coin, investors also make similar mistakes, pigeonholing threats and opportunities only within a narrow historic analog without appropriate context. With Silicon Valley Bank investors and depositors both decided to shoot first and ask questions later, mistaking poor risk management as equivalent to the asset and credit risk issues of 2008, perpetuating a run that no bank can avoid regardless of how much liquidity or safe assets they hold.

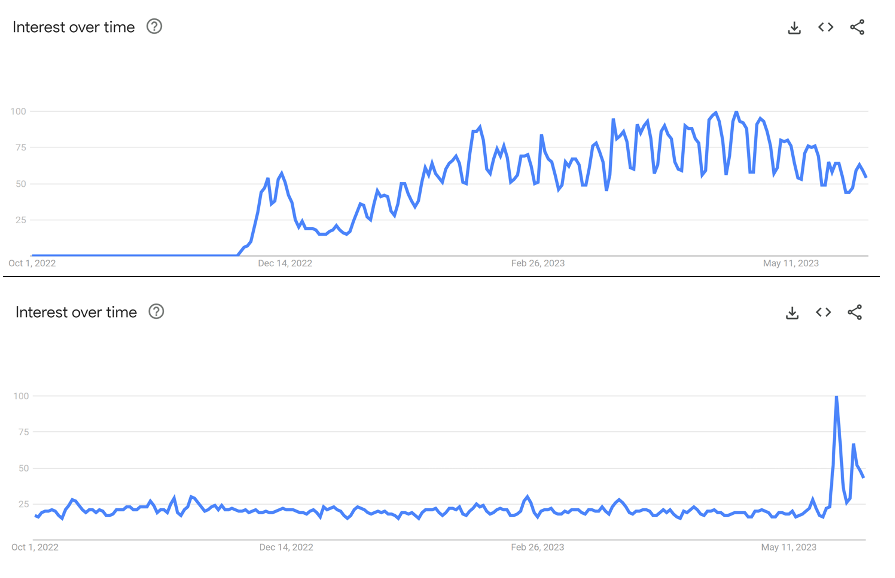

Which brings us to the markets’ topic du jour of late: artificial intelligence. Interest perked up substantially with the release of chatGPT last fall and then has reached another level with Nvidia’s earnings report a couple weeks ago.

Figure 1: Interest in chatGPT (Top) and Nvidia (Bottom) Has Made A.I. the Topic Du Jour

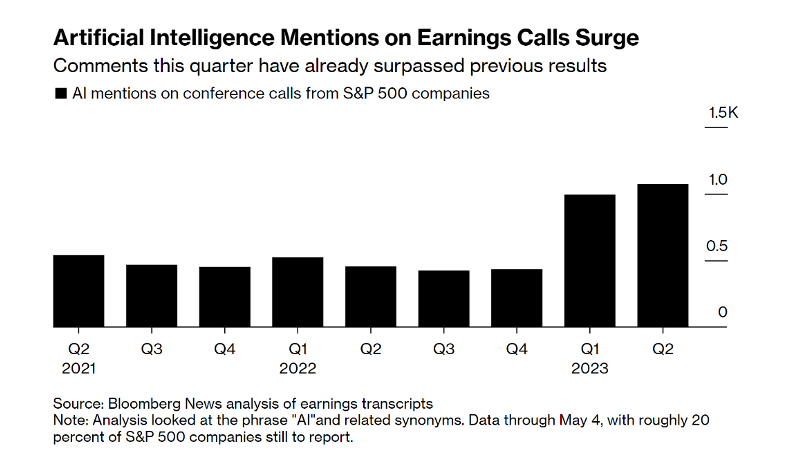

Microsoft – an investor in chatGPT creator OpenAI – and Nvidia – the dominant hardware supplier for training and executing these A.I. models – have seen their stock prices skyrocket. As what usually happens when markets become infatuated with a new toy, imitators quickly follow, hoping to ride the coattails of more legitimate players (Figure 2). Even the makers of Heinz ketchup couldn’t help but cite their use of artificial intelligence.

Figure 2: First Come Innovators and Then Imitators, Source: Bloomberg

It goes without saying that it is incredibly, incredibly early in the A.I. age. No one knows how pervasive or useful the technology will be, what the final or winning form and structure will look like, and who the beneficiaries will be. Without a clear vision for these, it’s not evident how investors should seek exposure. Some investors may think they know but more likely than not, they don’t. And you can start to see some evidence of shortcomings based on what type of commentary and narratives are being promoted.

For one, if artificial intelligence is truly groundbreaking and is the next phase of computing, then it will be so because of what it enables and creates rather than by what it replaces. I mention this because the dominant discussion and narrative being driven around chatGPT specifically is how it is a replacement of the search engine and the ramifications for one of the world’s largest profit pools. This is the epitome of fighting the last war. Moats are built and disruption happens when new use cases are brought to the forefront, not by unveiling a better mousetrap. The iPhone wasn’t a historic platform shift because its call quality was better than Nokia or Blackberry.

Second, and consequentially for investors, we have no idea how the economics of this new platform, if it materializes, will play out. If generative A.I. is something all incumbents have access to then it becomes difficult to see how any one company can price features in an accretive manner; once one company implements generative A.I. into their products to gain an advantage so will their competitors. The end result could be a status quo with added embedded costs. The dilemma rings similar to an old story Buffett tells about investments at Berkshire’s textile operations: “Many of our competitors, both domestic and foreign, were stepping up to the same kind of expenditures and, once enough companies did so, their reduced costs became the baseline for reduced prices industrywide.” This may not be the case with large language models but no one can equivocally say as of today that it isn’t. Relatedly, while many companies may seek to build upon and expand their A.I. offerings (which is why Nvidia was able to post such a historic quarter) there is no telling whether those investments will generate any meaningful ROI. (For those skeptical as to why such successful companies would burn money chasing potential without any confidence just look at today’s announcement by Apple of their mixed-reality headset and compare it to what Facebook/Meta has burned billions of dollars building.)

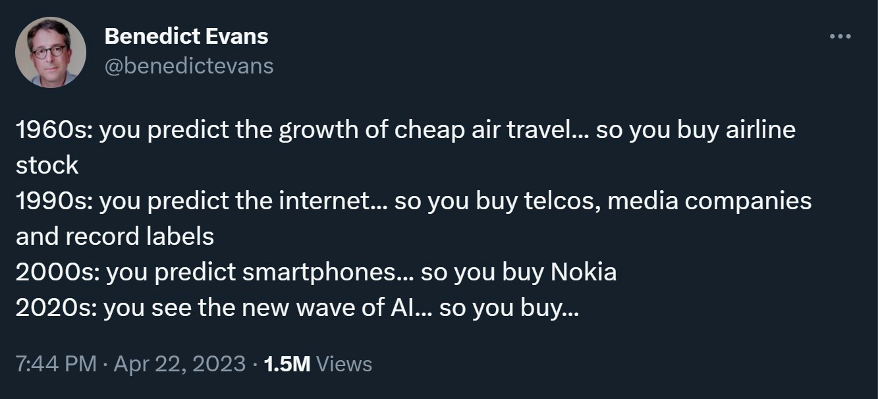

Finally, the real winners of any A.I. evolution may take decades to play out, if there are any winners to be had at all. It wouldn’t be at all inconsistent with some of the great innovations of the last several decades for the “obvious” early winner and beneficiary to turn out not to be a beneficiary at all. Benedict Evans, a respected technology commenter and former sell-side analyst, encapsulates this possibility well.