Invert, Always Invert

Invert, Always Invert

-

Author : The BlackSummit Team

Date : August 25, 2020

“All I want to know is where I’m going to die so I’ll never go there.”

– Charlie Munger

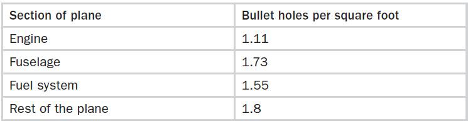

The role of aviation reached a new level in World War II and grew in strategic importance throughout the war years as technological improvements compounded capabilities. Allied forces in general, and Britain’s Royal Air Force specifically, initially struggled against Germany’s anti-artillery defenses, frequently losing aircraft after bombing campaigns. To protect against this problem, Allied forces sought ways to provide further armor to planes to increase their chance of survival. But because additional armor was costly in terms of weighing down planes, impacting maneuverability and fuel consumption, the reinforcement had to be targeted in an attempt to maximize benefits without burdening planes too much.

After examining and quantifying where returning planes were most impacted mathematicians and scientists at Columbia’s Statistical Research Group recommended adding more armor to protect the plane’s fuselage since it bore the brunt of enemy fire (Figure 1). By adding more armor to where planes were getting hit the most you could increase the survival rate of planes, or so it was believed by the English Air Ministry.

Figure 1: Aircraft Damage in World War 2 (Source: Jordan Ellenberg)

Abraham Wald however recommended instead that the additional armor go towards the engine of the plane, despite the fact that it received the fewest amount of bullet holes among returning planes. To Wald, the logic was backwards. If you want to know where to add more armor to planes you don’t look at the ones that are surviving. Rather, you look at the ones that are failing to survive. He inverted the problem and realized that what the data represented wasn’t where to add armor but which parts of the aircraft were more resilient. The reason the engine got hit less in the planes coming back is because they were more likely not to return at all.

While it may seem obvious, among some of the sharpest minds of their generation and when the stakes were highest it was only apparent to one individual. Similarly, sometimes the best ways to think about where and how to deploy capital are to first eliminate where it tends to be wasteful and destructive.

There’s a reason after all that between 1926 and 2016 over $35 trillion in wealth was created by 25,300 stocks listed in the U.S. Yet over half of those gains can be ascribed to 90 names, just one-third of one percent of listed companies. The ability for companies to provide durable and superior returns is only getting more difficult as technology replaces businesses, enables new competition and amplifies short-termism among shareholders, management teams, and their boards. It’s one reason why the average age of a listed company has fallen from almost 60 years old in the 1950s to less than 20 years old today. While all people are created equal, all companies and investment opportunities are not and occasionally it might simply be easier to avoid losers than to pick winners.

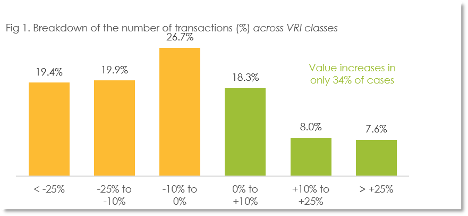

Figure 2: Two Thirds of M&A Deals Destroy Value (Source: Global PMI Partners)

Probably the most recognized and studied way in which value is destroyed is via mergers and acquisitions. While the measured impact of M&A on value creation varies from study to study it consistently ranks among the lowest, if not the very lowest, ways to create value. The ways in which they fail are numerous: hubris about what the future will look like (AOL and Time-Warner), excessive optimism on revenue synergies (ATT and DirecTV), self-serving interests (RJR Nabisco), and cultural clashes (HP and Compaq). Much like excessive exuberance can blind asset markets, corporate boardrooms fall under the same spell of only what can go right instead of what can go wrong. It’ wise to greet the rhetoric employed in press releases announcing M&A with a critical eye.

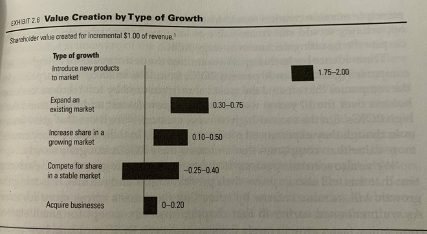

An additional, and more nuanced way in which value is often destroyed is related to the second worst growth driver in Figure 3: via commoditization. Commodities lack differentiation. The difference in gas that you put in your car from BP is infinitesimally miniscule from the gas at Shell that almost 10 times out of 10 you’ll go to the one with lower prices. That’s commoditization and it happens not just with raw materials but with businesses and products that we encounter every day. Mistaking a commodity for something of quality happens to the best of us, including Buffett.

Figure 3: What Type of Growth Creates the Most Value (McKinsey)

In his 1985 letter he writes of the decision to close down the company’s textile operations (from which the name Berkshire Hathaway derives). The business’ failure, according to Buffett, has nothing to do with poor management, labor productivity, technological disadvantages, or anything else. Rather, the industry operated in a global environment in which excess capacity put downward pressure on prices, the ultimate arbiter of who won business. And when you compete on price, you are effectively in a commodity business and condemned to mediocre returns.

It wasn’t for lack of trying. In fact, Buffett mentions that the textile business frequently encountered investment opportunities to lower costs with projections that “looked like an immediate winner. Measured by standard return-on-investment tests, in fact, these proposals usually promised greater economic benefits than would have resulted from comparable expenditures in our high-profitable candy and newspaper businesses.”

Greeted with such rosy projections Buffett agreed to the investments. And sure enough, costs were lowered just as promised by the projections. But the textile operations still didn’t turn around even with the new lower costs. Why? Because the same investments Berkshire was able to make to lower costs were also available to competitors. As a result, the value created fell not to Berkshire or other operators but instead to consumers in the form of lower prices:

“Many of our competitors, both domestic and foreign, were stepping up to the same kind of expenditures and, once enough companies did so, their reduced costs became the baseline for reduced prices industrywide.”

In essence, Berkshire had been commoditized. The ability to differentiate was miniscule and in such instances the most efficient/lowest priced operation wins. When one company was able to implement a new method to reduce costs it would see its share of the market rise but because the method of lower costs was not exclusive, it could be mimicked by competitors. As a result, investment levels would rise and prices would fall in order to get as much share as possible to cover the fixed costs of the new investment.

Investors fall in to some variation of the same trap all too often time after time. A new market opportunity opens up and investors simply think Company A will be able to sell more and that its earnings will rise, warranting an investment. They fail to consider the costs to acquire the new growth (ignoring the concept of return on investment), the effects competition will have, and other factors. Take the Personal Computer for example. Since my first computer over 20 years ago I’ve had probably had close to a dozen machines. Yet I never asked if the hard drive was made by Toshiba or Western Digital or Seagate or anyone else. I didn’t research who made the memory. It never entered into my thought process for choosing what to buy. What did though was whether it had an Operating System I was familiar with and had a processor capable of running the applications I needed to run. It’s no coincidence that the two main winners of the PC revolution were Microsoft and Intel. The other components were essentially commodities: they were indistinguishable from each other.

In essence, while they may create enormous value they do not capture that value for themselves. There’s no way to protect new innovations that increase revenue or lower costs as they can be mimicked by competitors. In short, they have no moat.

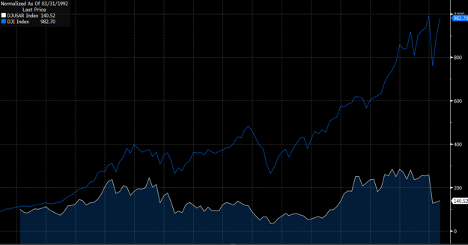

Instead the new value created gets passed on to other parts of the ecosystem, primarily end users in the form of lower prices, better features, or a combination of the two. No industry perhaps represents this phenomenon better than airlines (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Airlines (White) vs The Market (Blue): Incredibly Valuable to Society but Not Great Businesses

Airlines, grocers, and many other types of businesses are enormously valuable for society but great businesses they are not. Occasionally, someone can make money buying their securities. But in my experience those opportunities qualify more as trades rather than investments, the difference being that the former’s returns are driven by far more variables than just business quality and fundamentals including sentiment, randomness and dumb luck. Failure to recognize the delineation can be hazardous to your wealth.