The Wooden Nickel

The Wooden Nickel

-

Author : The BlackSummit Team

Date : July 16, 2024

The Wooden Nickel is a collection of roughly a handful of recent topics that have caught our attention. Here you’ll find current, open-ended thoughts. We wish to use this piece as a way to think out loud in public rather than formal proclamations or projections.

1. What You Must Believe

The discounted cash flow (DCF) model is a classic valuation tool. It’s taught to any beginning finance student and iterated upon relentlessly for anyone trying to make a career in banking, not to mention its classic application in investing. After all, a security’s intrinsic worth is the value of its future discounted cash flows.

A sometimes more useful exercise is to invert the DCF model. Rather than summing up an estimate of future cash flows to come up with a current price, start with the current price and work backward: what must you believe to be true in the future for a company’s growth trajectory, margin path, capital needs, etc. to justify paying the current market price?

And if there’s ever a company where I think such an exercise could have been useful it’s Nvidia because if there’s one thing that would have saved a lot of stress over the stock’s bears is if they would have taken their CEO, Jensen Huang, at his word when he intimated the computing revolution going on in the tech world today. While the world is infatuated with Artificial Intelligence, Huang has long warned and preached that Moore’s Law was dead and that the fabric of data center infrastructure would need a new model and overhaul for how to move computing forward; Huang refers to it as “accelerated computing” while others call it “heterogeneous computing.” In either case, the point is that the organizing principle, the center of gravity in the computing universe, was going to change and move away from the CPU.

Trillions have been invested over decades and it all needs to be replaced if you believe Jensen. Most have scoffed at the notion (sometimes with legitimate reasons) and seen the stock’s price rip regardless. Which is why I loved Richard Jarc’s recent analysis. He didn’t fight the grandiose assumptions laid out there; he took Huang at his word and the conclusion is quite fascinating. It really is worth reading his analysis in its entirety (both to appreciate Nvidia as a business and also as a good example of simple, but not simplistic, investment thinking) but the highlights are:

If you take Nvidia’s lavish goals over the coming years, give it a terminal multiple of 25x (far above the market’s 16x-18x), using a discount rate equivalent to what the United State’s government has to pay to borrow money, the resultant equity value is “$3.6T, and the company is trading at $3.4T. That means a 5.88% return above the risk-free rate. I’ll leave it to everyone to come to a conclusion about whether that makes sense as an investment.”

2. Room to Cut

We made the case in April that, for better or worse, the current Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) leans dovish and that some relatively recent history supported that supposition. The Fed’s default desires were to cut rates heading into this year and by being anchored on such a position, they needed to be actively dissuaded rather than persuaded; inertia sat in the camp of lower rates in the not-too-distant future.

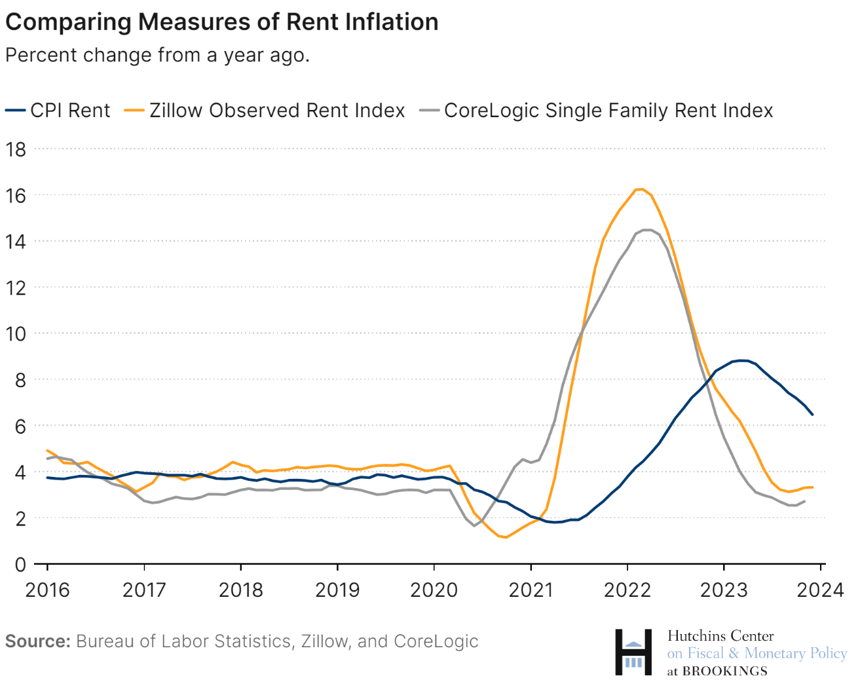

Inflation bulls and bears have interpreted the data vastly differently over the course of this economic cycle: some focusing on the overall figures, others on core measures, and others even relying on a “super” core figure (core services ex-housing) as being a more accurate read of underlying inflation pressures due to pandemic related volatility or other exogenous and unsustainable factors. But if there’s one area where there’s been some semblance of agreement it’s in the CPI’s measurement of housing. It’s slow to update and doesn’t quickly incorporate market-level activity for rental rates; it lags actual rent transactions by over a year.

Figure 1: CPI Rent Lags Market Transactions, Source: Brookings

Thus, both tended to agree that CPI levels were a bit inflated (pardon the pun) by lagging measures of rent costs. But how much to discount it? Do we look at it on a core basis? The most generative and punitive, if you were a monetary policy hawk, would be to say keep everything in the CPI basket except for shelter. What do you get? The answer is in Figure 2.

Figure 2: CPI Has been at 2% For a Year

The answer is that even the most punitive reading of inflation (where car prices and auto insurance and medical expenses and airfares, which are all volatile, stay in) is not only below 2% but has been there for a year. Furthermore, these pricing levels are entirely consistent with the pre-COVID path of price stability. After the acceleration scare on pricing earlier this year, if you’re a dovish FOMC member at your core waiting for confirmation you’ve probably gotten it, barring a surprise over the next two months.

3. Macro Table Stakes

There’s a great scene in the film Zero Dark Thirty where the Director of the CIA is getting his team’s assessment on the odds the monitored compound actually houses bin Laden or not. While just about everyone in the clip couches their view with some level of uncertainty, the low-level analyst in the room says she’s “100%” certain he’s there. The clip ends with the Director in the elevator with one of his advisers and he asks, “What do you think of the girl?” “I think she’s smart” is the adviser’s reply. Annoyed, the Director claps back “We’re all smart.”

I love that ending exchange for two reasons. First, because it acknowledges the probabilistic nature of so much of what we encounter, no matter how annoying that nature may be. Second, it derides a statement, although being true, because it is unhelpful. It’s table stakes. It offers no specifics about the issue at hand, and it fails to compel anything of the recipient: not to acknowledge a new set of facts, not a new perspective, not a new synthesis of what is already known. There is no connection between the data point and what must follow. The most appropriate response to an assessment of that kind is “So what?”

It reminds me so much of how people evaluate macroeconomic data points and try to incorporate them into portfolio construction. Α growing economy is good for everyone. It tells you nothing if Oracle will upgrade customers to their newest database, or if Molson Coors’ marketing is being effective, or if Charter Communications is going to lose share to fiber companies or fixed-wireless providers. There’s an endless number of permutations and paths between a macroeconomic data point and the decision in front of you as an investor or allocator. The data, more often than not, is table stakes to the bulk of the job.

- If you’re an allocator, is examining GDP growth going to help you to decide if a broad market investment in Germany or South Korea is more appropriate? Because the former has been contracting for 3 of the last 4 quarters and its stock market is at all-time highs, after a hiking cycle, while the latter hasn’t had a recession since Covid and has gained 5% cumulatively in the last 4 plus years.

- Is evaluating the ISM reports, retail sales, or the jobs report going to help you understand whether to allocate more to insurers an HVAC distributor, or a mortgage-REIT? The type of top-down macro/investing analysis that I see far too often paints far too broad a brush.

- There is no one economic cycle; it’s the aggregation of tens of thousands of other cycles playing out in real time. Just in the past year, we’ve seen down cycles in networking equipment and spirits while industries like insurance have accelerated.

- If it was so simple as to distill investing from macro inputs then why wouldn’t everyone be on the same side? How would a market form? Is discounting dead? Does valuation matter?

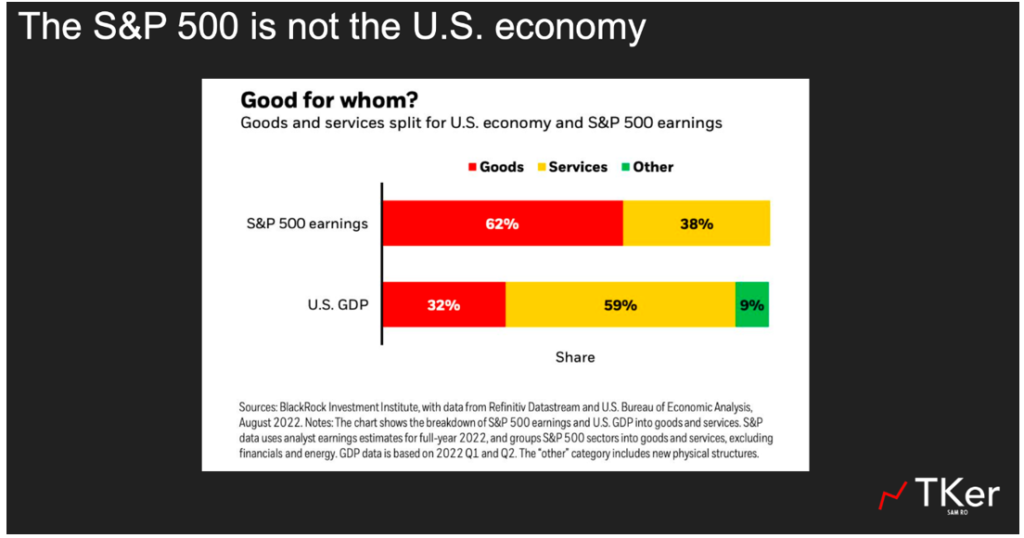

Economic analysis and portfolio construction are no doubt related; corporations do not exist in a vacuum. But the fibers that connect them have layers upon layers of other matter in between that prevent the utility and wisdom of simple linear extrapolations. The stock market is not the economy.

Figure 3: The Stock Market is not the Economy, Source: Sam Ro

When done well, macroeconomic data and its analysis are context for earnings and valuations. It helps function as a dial for the amount of general risk level that should be in portfolios. But when it tries to actually enter into the investment selection process, too much energy is being expended for too little return.

4. Recommended Reads and Listens