I received an interesting memo from our “Questions No One is Asking” department this week: Is market timing really all that bad? “Of course it is,” I scoffed. “Any freshman finance major could tell you that!” But before I threw the memo away, a headline caught my eye:

If Warren Buffett felt the need to address one of the sacred cows of investment heuristics, at least one person is asking the question. So after reorganizing the “Questions No One is Asking” department into the “Questions at Least One Person is Asking” department, I decided to investigate the question myself.

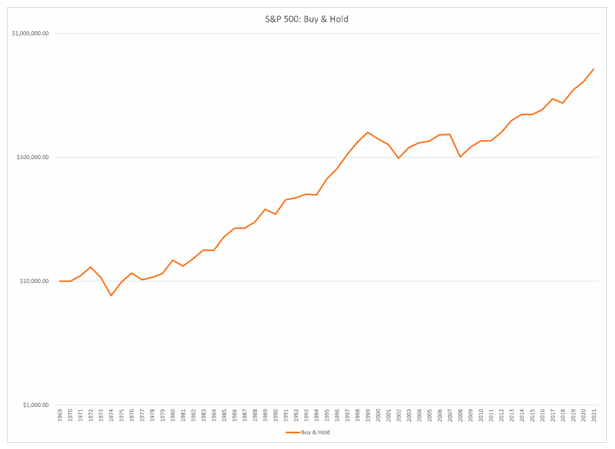

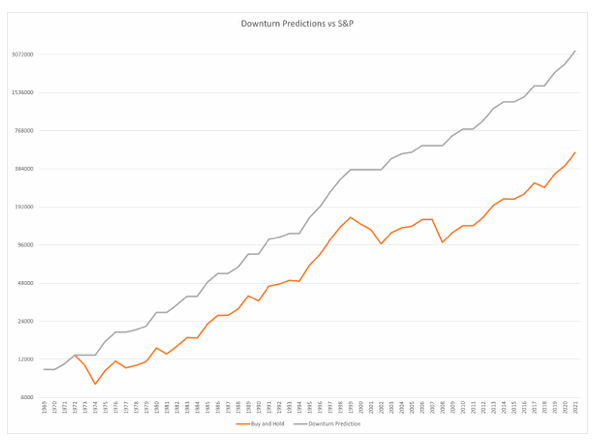

In any experiment, it is important to have a control group. In honor of Buffett, we’ll use a buy-and-hold investment style. The chart below shows the total return of $10,000 invested in the S&P 500 from 1970 to 2021. The chart is logarithmic for reasons that will become apparent shortly.

If you had bought $10,000 of the S&P in January 1970 and forgot about it until last December, your account would have been sitting at $515,820! That’s an annualized return of about 8%.

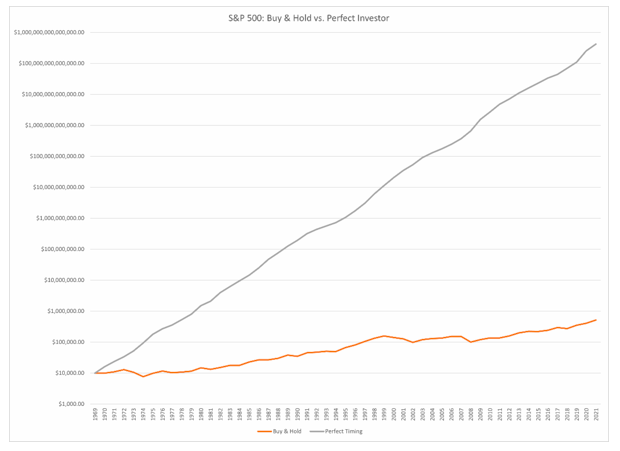

Now let’s see what an investor with perfect knowledge of the future could do.

No wonder market timing holds such appeal! If you could perfectly predict whether the market will close up or down next week, you could make an annualized return of 61.5% per year. Your $10,000 invested in 1970 would grow to over $418 trillion by 2021!

If you’re like me, you saw that number and thought, “I could be right about next week’s returns an absurdly low number of times (i.e. 0.25%, or once every four years or so) and still make $1 trillion (0.25% of %418 trillion) in 50 years?” Unfortunately for my portfolio, this is not how compound interest works.

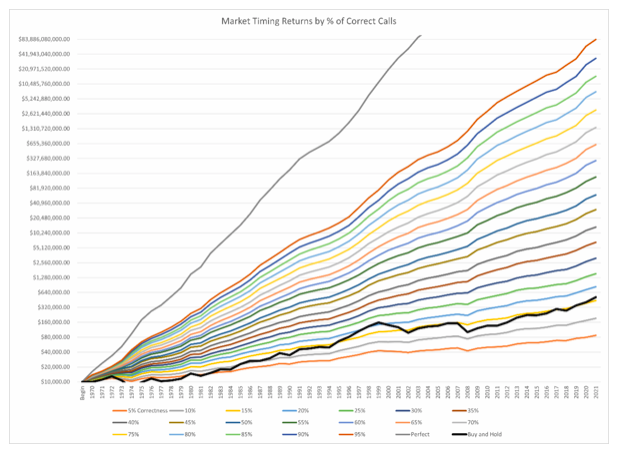

To show this, I modeled a few more portfolios with varying degrees of accuracy in predicting the next week’s closing price.

As shown above, every 5% loss of accuracy roughly halves the total return of the portfolio; if I am accurate in my prediction less than 20% of the time, I will actually end up underperforming the S&P. And this scenario assumes that when I am not making an ideal trade (I hold), I do not make trades in the wrong direction, buying when I should sell or vice versa. By adding in the possibility of incorrect trades, the prospects diminish further.

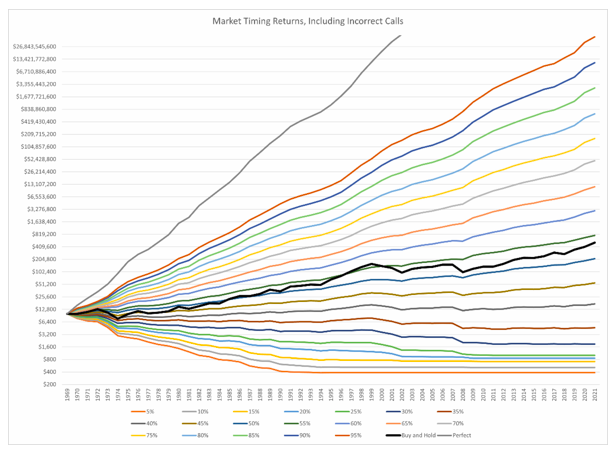

When we add in the possibility of being wrong, we would need to be accurate more than 50% of the time to beat the S&P in the long run, which is far easier said than done (one need look only at the sea of index-lagging mutual funds to see the truth of this).

While the short term is notoriously difficult to predict, in the long run there are predictable macro-scale factors that influence the markets, such as geopolitical interactions (e.g. the Russian invasion), economic indicators (e.g. China’s looming debt problem), and general cyclicity. How to interpret these indicators is the topic of another commentary – the idea is that some (though not all) market moves can be predicted, specifically to the downside, and anticipating these movements pays off.

For our last scenario, we’ll look at an investor who can successfully predict when the S&P will end the year in the red.

The investor wary of down years can generate a 12% annualized growth, well ahead of the S&P.

Of course, this is only a surface-level analysis. There is far more data analysis to be done relating to investor confidence, macroeconomic influences, and market efficiency. But recognizing the danger of timing the markets reinforces the first lesson of investing: humility. No analysis is complete, nor any strategy foolproof. As long as humans participate in the market, there will be risk in the uncertainty. But that is the beauty of enterprise – because of the disorder and danger, the virtues of creativity and excellence are cultivated. Value is thus created not only in monetary terms, but also in the realm of human progress.