Vladimir and Estragon are still waiting for Mr. Godot as the curtain falls in one of the greatest plays written by Samuel Beckett. Who is really Mr. Godot and why doesn’t he ever appear in the play? And why is the slave owner blinded and the same boy keeps coming to announce that Mr. Godot will come but on a later day and time, which actually never materializes? Are they possibly waiting for the wrong Mr. Godot at the wrong place and time?

In 1969, Samuel Beckett won the Nobel Prize in Literature and the Nobel Committee cited “Waiting for Godot” as one of his greatest achievements. The play actually ushered in a new era of possibility for drama. It’s one of the first pieces of absurdist theater which is very fitting in the era of absurdity that has been ushered in lately. In our era of absurdity, we expect central banks to keep inflating their balance sheets, throw money from helicopters, and bail out everyone, while budget deficits keep growing and national debts are becoming even more unsustainable. Of course, we find ways to justify the indefensible, while our quivers are enhanced every month with arguments of why a price-to-sales ratio of 5+ makes perfect sense.

We chose to call the economic theater of the absurd the “wilderness of mirrors”. In that wilderness that covers almost the last 50 years (since August 15, 1971), there have been structural and regulatory changes (especially the ones initiated by the trinity of Greenspan, Rubin, and Summers in the 1990s) which have created deserts of liabilities, which in turn require constant bailouts and central authorities’ feeding (of governments and central banks). The result has been a prosperity bought on credit which frequently creates crises, that in turn would require more feeding. We are all now subscribed to the dogma that debt is a panacea for all our troubles.

- Bankers overextended credit? No problem, we have the debt weapon in our toolbox.

- Borrowers overextended themselves? No worries, we can loan them more funds.

- Politicians took us to war for non-existent WMDs? We will spend a couple of trillions and perpetuate borrowed prosperity.

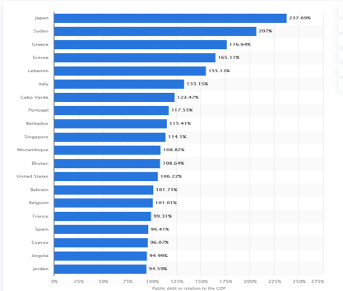

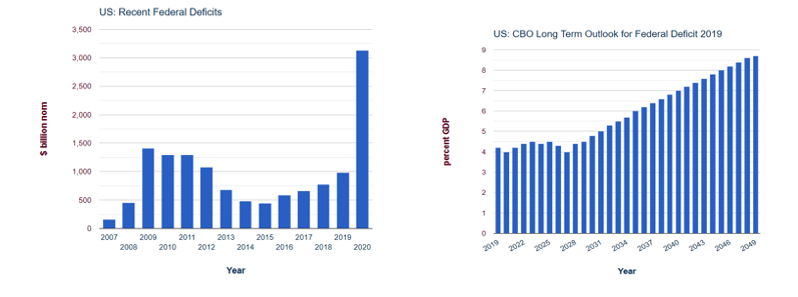

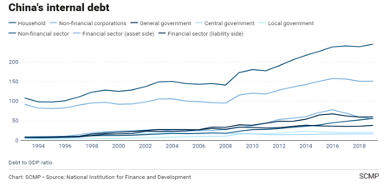

The first graph below portrays a picture of national debts as a fraction of respective GDP, the second one reflects the growing trends in US federal deficits from historic and projected perspective, while the third one shows China’s internal debt which is nothing but “The Great Wall of Steroids”.

Please do not misunderstand us. During a pandemic some major but targeted spending is needed, but prevention (in terms of being ready as well as taking precautionary measures), and punishment of the perpetrators who should compensate for the damage they inflicted in the world, are much better, In our humble opinion, than standing in awe of 83K infection cases a day and planning the spending of another two trillion dollars.

I understand the case that we need to save medium and small size businesses that generate more than 60% of employment in the US and in Europe, but we also understand (maybe in a limited way) historical circumstances where debt accumulation destroyed countries, empires, and whole continents. We also understand that in the absurd theater of debt accumulation and financial repression, extremely low interest rates can afford the countries more borrowing (even financed by central banks) in the name of “restoring prosperity.” We get all that, but our question remains: Until when can we afford such actions and what will we do if markets start pricing additional debt as unaffordable by driving long term interest rates higher? Who will pick up the bill at that time, or are we willing to wipe out the debt via inflation or another major war?

We hope, envision, and foresee that a significant structural change is forthcoming in terms of major infrastructure spending. We only hope that it will be such that can underwrite a significant productivity revolution, which along with the evolution that is undergoing in the tech and biotech sectors, can resemble the “Glorious Bloodless Revolution” i.e. underwrite unparallel institutionalized changes, similar to the one ushered in England in 1688, and truly revolutionized the world, while setting the solid foundations of an empire which came with all its faults and weaknesses but because of the “Glorious Bloodless Revolution” gave us the Industrial Revolution. If we are correct in our assessment, then it is obvious that investors should start looking into infrastructure and industrial plays soon, along with plays in the renewable sector and the companies that empower those sectors.

In his play, Samuel Beckett taught us that the inherent meaning of life comes in conservation of our highest ideals, and in satisfying our existential inquiries by living out our values, and not meaninglessly waiting for Mr. Godot at the wrong place and time. Failing to do so will simply imply that we pathetically accept an absolute absurdity of existence in lack of intrinsic purpose.