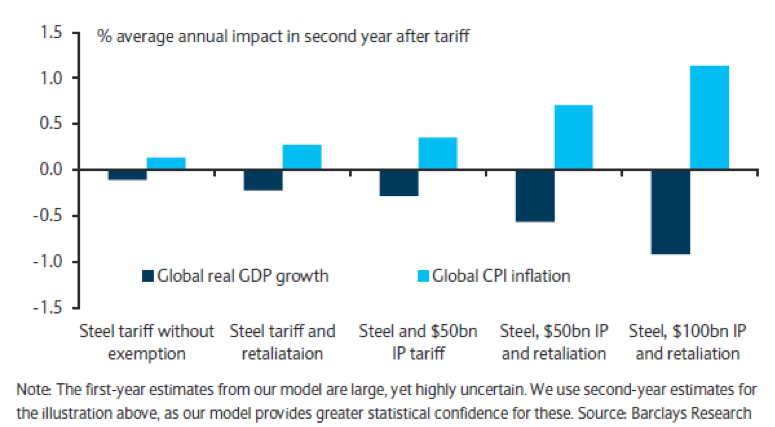

Emerging and developed markets depend to some extent on a China-centric supply chain. As trade tensions between the US and China (as well as between the US and the EU) are rising, that supply chain is subject to interruptions. The more of those interruptions occur, the more susceptible trade becomes to becoming an inflationary force. If such trade disputes evolve into a full-blown trade war, then we could say that with great probability three effects would be lower growth, lower incomes, and higher inflation, as the graphs below show.

As monetary policy is tightening, the dollar is expected to strengthen at a time when the reliance of emerging markets on dollar refinancing of their debts may be intensifying. Therefore, the pressures on emerging markets are rising. Emerging market debt is close to $11.5 trillion dollars and that does not include off-balance sheet debts. As energy prices rise, inflationary and pressures may reverse carry trades which in turn will amplify tensions and conflicts.

The total tariffs (those already imposed and those yet to materialize) on Chinese imports represent close to 1.5% of China’s GDP, which obviously (if those tariffs materialize) will affect immediately China’s growth and emerging markets’ growth prospects, and will weaken China’s and emerging markets’ currencies, probably exacerbating trade conflicts.

At a time when Chinese and European growth is facing some considerable headwinds, increasing trading conflicts (seen in the retaliatory actions of China, Mexico, the EU, and Canada) may give rise to an inflationary undercurrent that we may call conflict inflation, which in turn could undermine capital formation and investment spending. Such conflict inflation might be considered benign so far, but if autos are included in the trade disputes, then we will be openly talking about a trade war, and – as the first graph above illustrated – the impact on inflation could be significant.

A potential 25% tariff on auto parts could inflict major damage to supply chains across North America, but the impact on Japan, Germany, and South Korea could be severe. We cannot exclude the possibility that if those actions escalate, the US administration may withdraw from the WTO which will isolate the US and may be the cornerstone of the next major recession.

As our commentary of last week explained, we prefer a more conservative asset allocation for the sake of capital preservation.