The Wooden Nickel is a collection of roughly a handful of recent topics that have caught our attention. Here you’ll find current, open-ended thoughts. We wish to use this piece as a way to think out loud in public rather than formal proclamations or projections.

1. Obliteration Day

In no particular order and an inexhaustive list:

- The belief that a country should have equal levels of trade with each and any country is absurd. It would be equivalent to expecting a barber to have to live his life by making sure he had a grocer, a doctor, and an accountant as clients in order for him to have food, medicine, and pay his taxes. This is worse and far more backwards than the mercantilist labels ascribed to the tariffs and their advocates. This is an ancient barter economic model.

- The tariffs are structured in such a way that it conveys a belief that any trade deficit should be eliminated. A trade deficit is not equivalent to trade barriers, let alone cheating. It is a further embarrassment that the implementation of illiterate trade policies was done with such error and recklessness that the applied rates are 4x higher than their own nonsensical policies desired.

- Further, trade deficits and imports themselves, when calculating GDP, are more of a residual, rather than explicit, calculation (see here). As a result, some of our largest trade deficits are significantly overstated. Take, for example, China. While the trade deficit with China is ~$300 billion, it does not account for the fact that many American firms are present in China and sell into the country. Adjusting for this dramatically changes the math.

Figure 1: Trade Deficits Don’t Tell the Whole Story, Source: JP Morgan

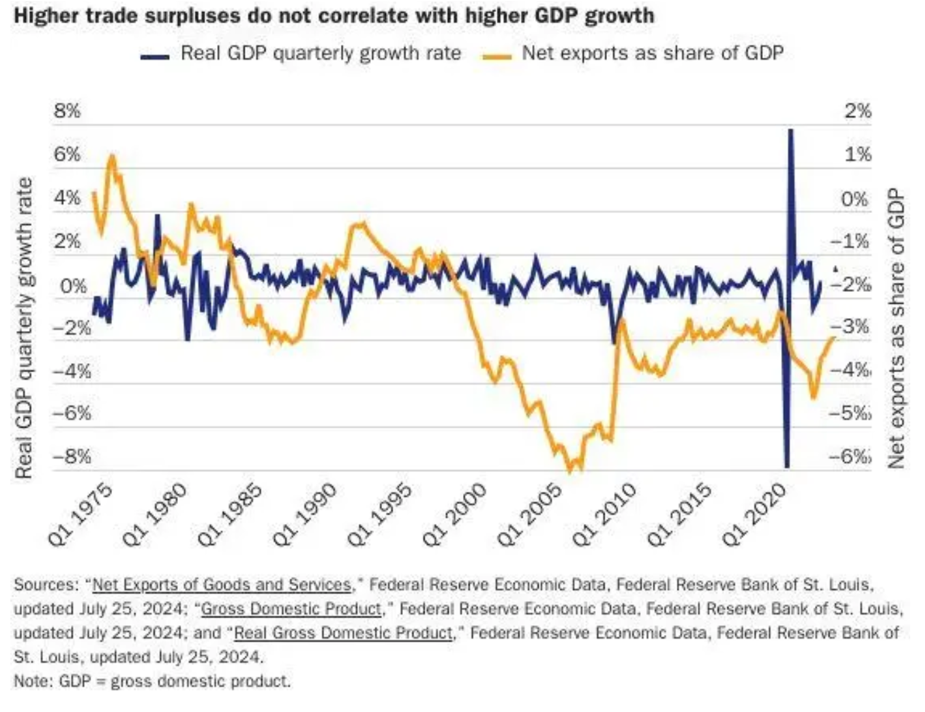

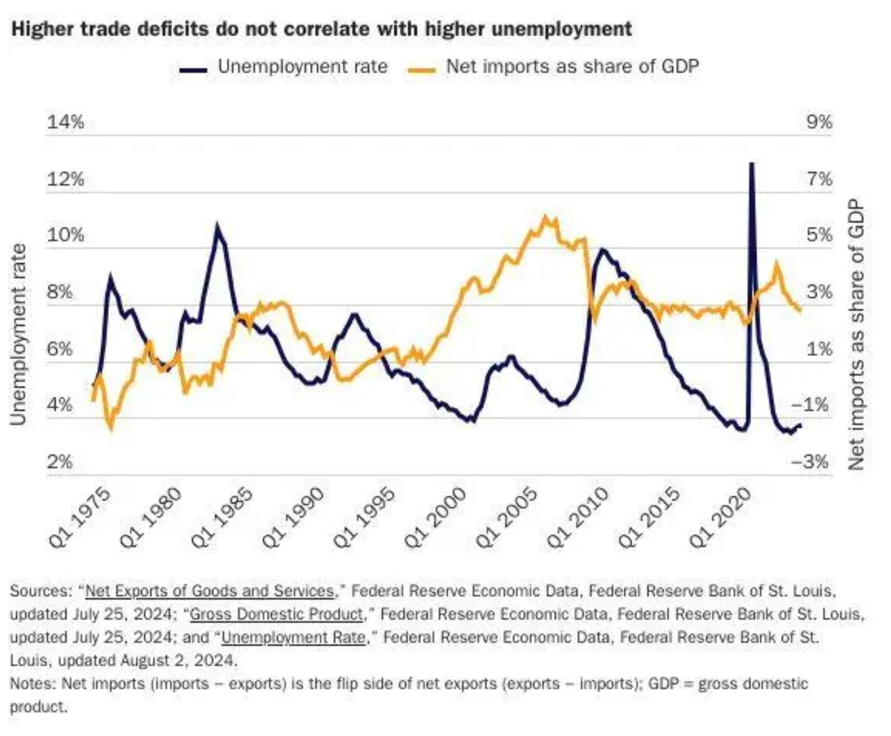

The persistent trade deficit of the U.S. has no relationship to employment levels, has no bearing on economic growth, and is nowhere close to a leading explanatory variable for any debt concerns the country has.

Figure 2: Trade and GDP Have Not Been Correlated, Source: Cato Institute

Figure 3: Rising Imports Tend to Be Associated with Lower Unemployment, Not More, Source: Cato Institute

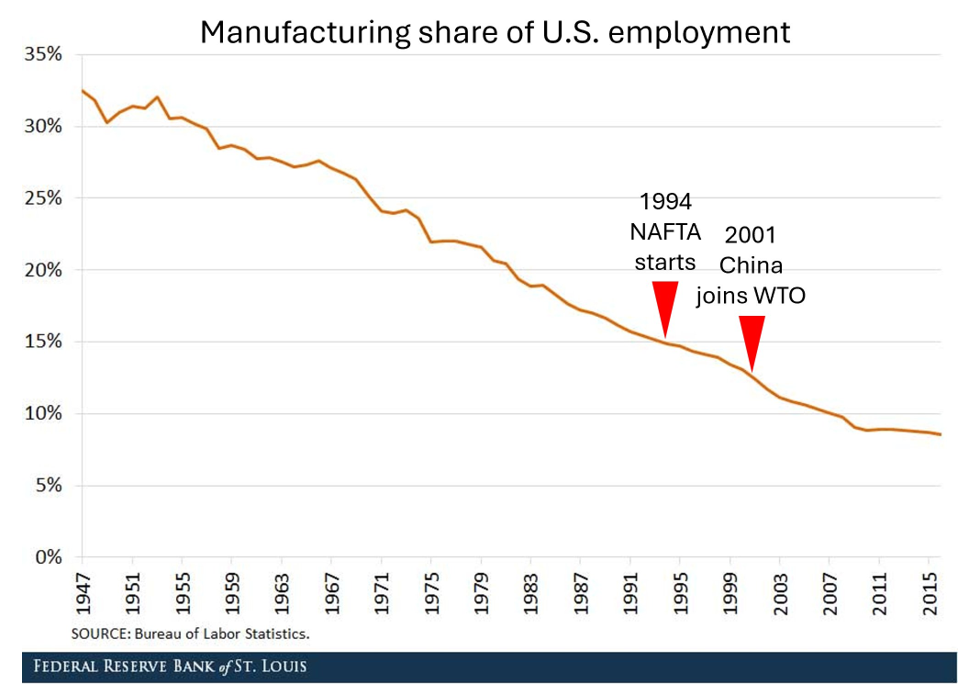

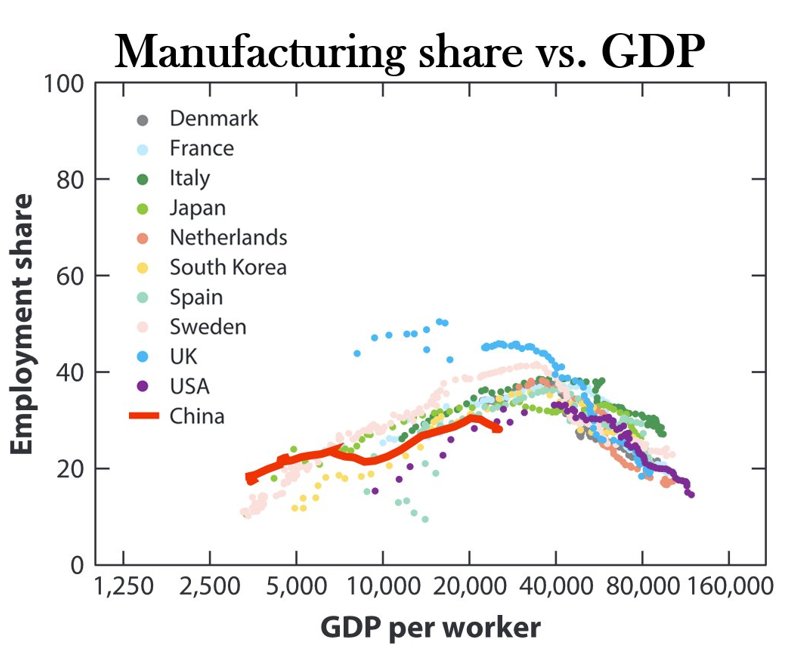

Employment in manufacturing has declined in all advanced economies for decades, including those with trade surpluses. And for the U.S. specifically, manufacturing employment has steadily declined regardless of trade policies/agreements, deficit levels, currency levels, and a wide range of other indicators. It is a symptom of people’s natural desire to work in higher levels of the value chain as income levels rise and higher value-add jobs become more plentiful.

Figure 4: Manufacturing Share of Employment Declines Naturally as Countries Get Wealthier, Regardless of Surplus or Deficits

Finally, median income levels in the United States, adjusted for inflation, have steadily risen for decades. The various claims that the U.S. has been ripped off from free trade and led to disproportionate job losses, deindustrialization, and competitiveness is bunk.

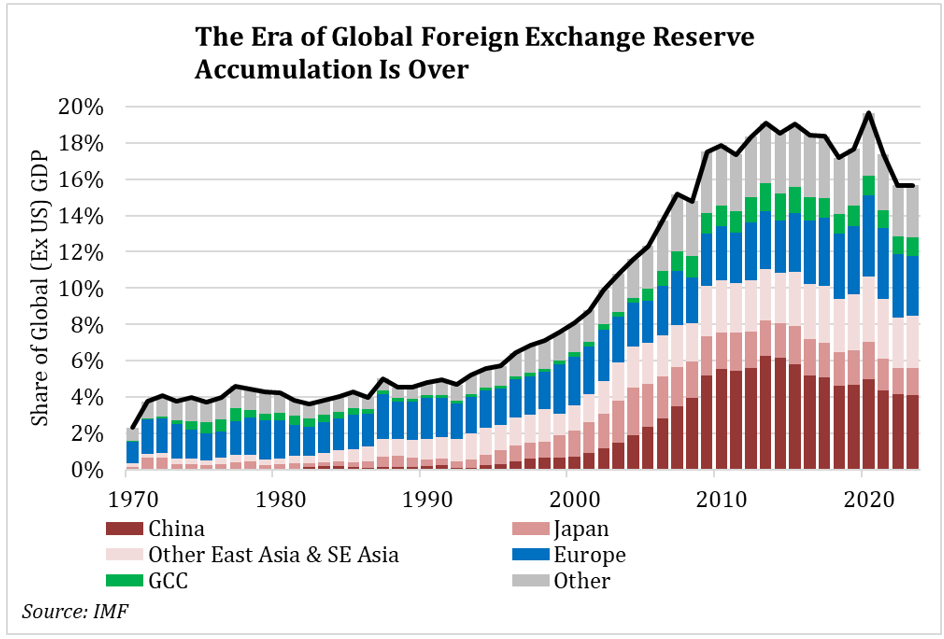

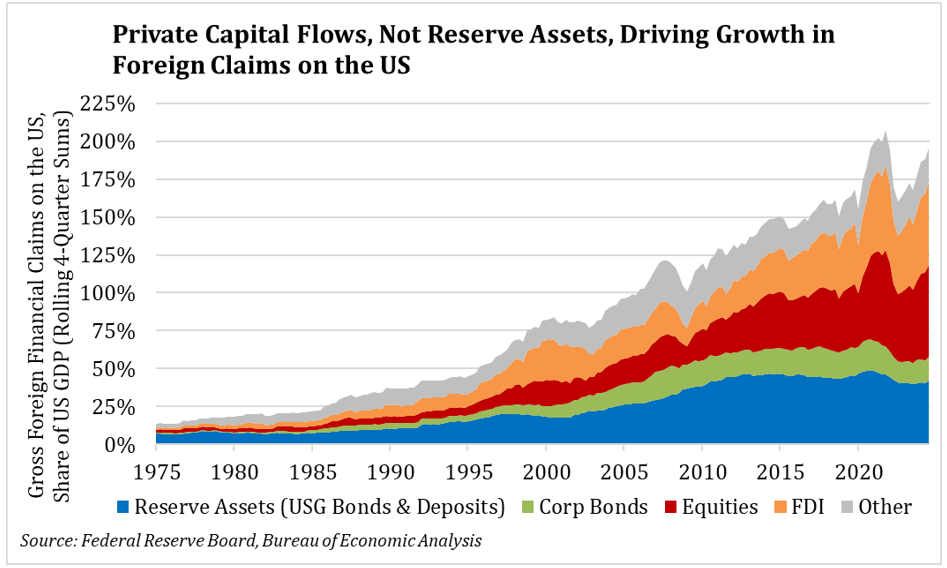

The idea that global dollar reserves is the source of these alleged ills is without merit. Reserve accumulation peaked essentially a decade ago. Instead, the global demand for dollars is due to the private sector making decisions on where their capital will be treated best. Due to the superior economic growth, productivity, returns on invested capital, and institutional strength, they have sought out the U.S. Being the most desired destination for global capital is not a problem. It is not in need of a fix.

Figure 6: Reserve Accumulation Peaked Over a Decade Ago, Source: Gerard DiPippo of RAND Institute

Figure 7: Private Capital, Not Reserve Assets, Explain Growing Demand for Dollars, Source: Gerard DiPippo of RAND Institute

Tackling the most challenging and ferocious geostrategic problems requires an abundance of resources and a plethora of associate partners, not a scarcity of both. Capital destruction and financial repression is no way to achieve economic superiority or technological supremacy.

2. Paradoxes

“The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science.” – Albert Einstein

Rather than variety, I would posit that paradox is the true “spice of life.” Stand over the Grand Canyon, one can’t help but feel small, but in a manner that is fulfilling and glorious. And yet in other contexts, feeling small is more associated with times of despair or hopelessness. Rather than being mutually exclusive, it is in that tension that paradoxes reveal the fullness of our humanity, the blending of art and science. On a more corporate level, the juxtaposition posed by a paradox inspires creativity that feeds both the stomach and the soul.

For months, since the election, chatter has slowly and then quickly grown about the potential for a “Mar-A-Lago” accord. The foundational premise being that for decades, the global economic system that revolves around the U.S. and the dollar has been more burden than benefit, resulting in job loss, the erosion of the middle class, a loss of export competitiveness, and vulnerable supply chains that threaten national security. The remedies involve unilateral efforts to reshape trade flows, currency arrangements, capital flows, and the national debt. Tariffs are the opening salvo in this quest and there is great risk in not believing there is more coming down the road.

Like much of what is passed off as rigorous intellectual work from this policy class, the economic underpinnings of proposed ideas are nonsensical, incoherent, if not outright dangerous. It is littered with contradictions, inaccurate data and understandings of global affairs, and extrapolates with a broad brush all the “ills” of the world down to a silver bullet.

Beyond the obvious, there is no grand strategy here (just sequential, zero sum, race to the bottom type of thinking), the most damning part in the thinking is a contradiction. The US economy is the envy of the world. It has been for decades, going back to WWII and through every crisis since. Covid revealed the same thing whereby economic growth was superior to every other developed nation, productivity was far, far better in recovery, and inflation fell much faster. Yet there is a certain class of “thinker” who insist that we’ve been on a one-way street of being held hostage by the rest of the world and that the only way to rectify the situation is to use our unilateral abilities to change the terms.

I wonder, does no one realize that the mere fact that we have unilateral capacity and instruments is a reflection of something unique and valuable and that rearchitecting things sacrifices this very ability and thus puts us on more relatively equal footing with the rest of the world? It should be well understood that you do not get ahead in life by playing the same games as everyone else. Being set apart by behaving the same as everyone else are antithetical ideas. So why is it that from an economic and geostrategic perspective we expect to drive to a world with more similar characteristics to the globe and expect that to elevate us?

This is the opposite of paradox. Instead of illuminating and refining, it’s a gnashing destruction.

3. The Worst Thing of All

Perhaps the most disheartening thing of all this (the policy proposals, the papers, the speeches, and podcasts from the administration) is the reflex of victimization, despair, and dystopian demeanor. It’s a living, breathing persecution complex.

In 2016, the Economist (accurately) warned of Trump’s zero-sum mentality and approach to all things. Multi-variable thinking and diagnoses are too complex, so everything gets whittled down to a binary and zero-sum type of framework, like viewing trade deficits as a subsidy. A trade deficit is no more a subsidy than my purchases of groceries are a subsidy to Kroger…to which the apparent “remedy” is to force myself to shop at Whole Foods. The actions of the past week are the apex of this thinking. It’s rooted in misinformation, incoherence, contradiction, ignorance, but worst of all, a victim complex.

This country has greeted problems and threats far more severe than those facing us today. And the brilliant moments in the past 80 years involved building positive-sum solutions and institutions. Naziism was met with lend-lease. Reconstruction of WWII was met with the Marshall Plan. NATO was a deterrent to hot conflicts with our greatest adversaries.

And yet, here we are today with a fixation on the crudest and reductionist vision for what is valuable. The first term saw fixations with corn, soybeans, and steel. Literal commodities. The most bottom rung of the global economic value chain. There is a reason so many resource-rich nations are cursed and why they orient their futures towards climbing the value-added ladder.

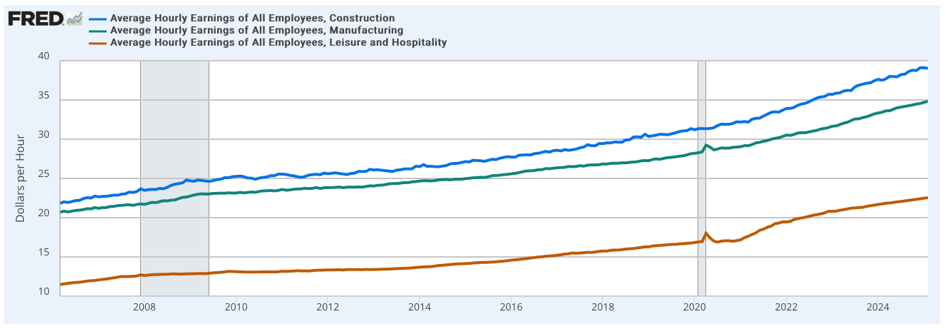

If we’re really worried about middle-class jobs, is there really nothing to be examined in our education system? We know that there is a shortage of trade jobs (jobs that pay very well in many circumstances). Why do we run away from incentivizing these jobs rather than seeking to lash out in victimization? If we seek out improving human welfare and human flourishing then is there nothing to examine in the regulatory morass that is our nuclear energy complex? Why is it, instead of thinking long and hard about why Austin, TX, can find ways to lower housing prices (but San Francisco, CA, cannot), we look to tax lumber imports and think that will buoy the American dream of home ownership for younger generations? If the concern is the quality of middle-class, blue-collar jobs (despite abundant evidence to the contrary), why not meet the moment with maximizing opportunities in construction, which pays better than manufacturing, by reducing red-tape and undergoing much needed permitting reform? Doing so addresses class inequalities that some fear, boosts incomes, raises GDPs, avoids economic costs/contraction, and, of course, doesn’t jeopardize the geopolitical order.

Figure 8: Construction Jobs Pay More Than Manufacturing, and the Gap is Widening

If we’re worried about supply chain vulnerabilities in times of conflict, then is it better to make enemies among our allies and seek out gains at their expense? Or would it be better to try and devise some sort of Economic NATO, an alliance whereby it’s agreed upon that in times of conflict critical resources first meet the needs of military allies before being open to the market (especially those allies, ie the U.S., that do the disproportionate share of the fighting and security). Or what about a new Marshall Plan where supply chains are moved from our greatest geopolitical adversary to more honest and friendly allies in the region? Yes it is ok to sometimes give financial welfare a backseat to other issues (that’s the whole point of an “externality”). But that’s far different from saying any action that takes a backseat to financial welfare is in our interest. That’s the point of appreciating paradoxes.

This Mar-a-Lago vision is too small for me.

4. Where Do We Go From Here

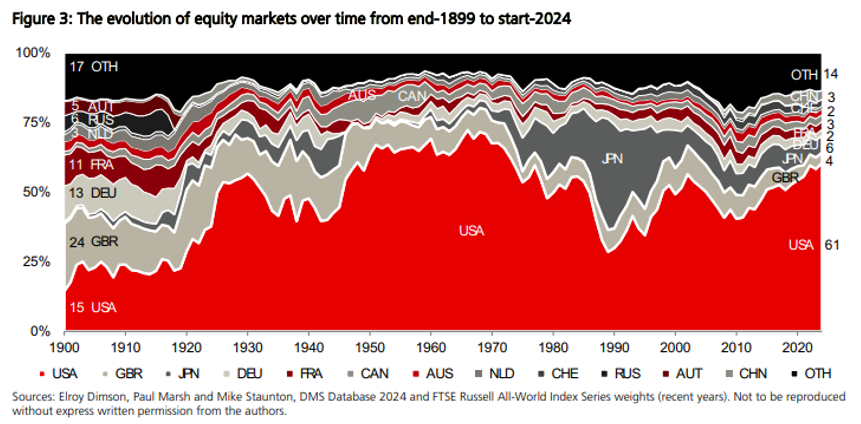

There is downside from here even if the entirety of all tariffs are removed tomorrow. For one, global investment allocations have become lopsided. Year-to-date investments in U.S. equity and credit were two times their European counterparts before the correction began in February, and in private markets, the U.S. attracts 70 cents of each dollar available for investing. We’ve approached levels of excessive U.S. allocation, levels rarely surpassed in history, and that has left U.S. markets vulnerable at the faintest of catalysts. Global pension funds, insurance funds, professional investors, etc., have piled into U.S. assets for years. With the incentive and motivation for the rest of the economies of the world to boost internal growth, capital flows could follow.

Figure 9: US Allocations Have Rarely Been More Concentrated, Source: UBS

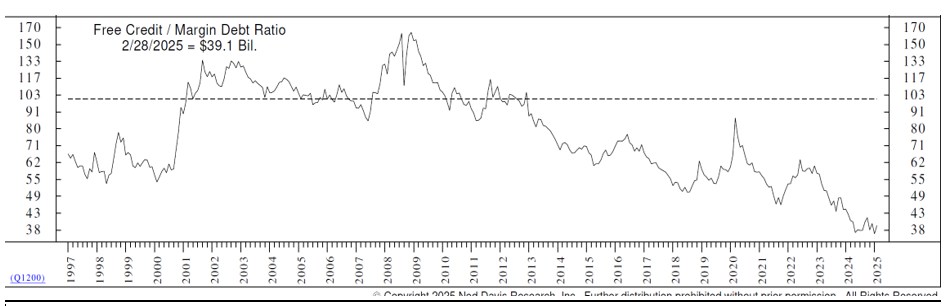

Second, like most phases of euphoria, the current market has been levered. Margin debt and credit facilities to participate in risk markets are at some of their most extreme levels. Bringing this back in line can lead to further declines even before we get to any fundamental discussion on what tariffs will do to earnings. These are reasons for an even moderate decline after the damage already seen.

Figure 10: Market Participation Has Been Levered, Source: Ned Davis

The more severe case is a severe recession in the U.S. Even with greater impulses for domestic investment and growth from places like Europe, Japan, and China, I doubt the global economy can withstand a contractionary U.S.; when the U.S. economy sneezes, the rest of the world catches a cold. A mild decline in earnings of 10% and a recent average-ish multiple, and we’re looking at an S&P 500 that is in the low 4,000s or the mid-3,000s. Most recessions bottom with more severe declines in earnings and well below-average multiples. Further, the inflationary potential of tariffs puts the economy in a quagmire and the Fed on the sideline until economic damage gets much, much worse; it would take far more than an equity markets meltdown to bring Fed Funds down.

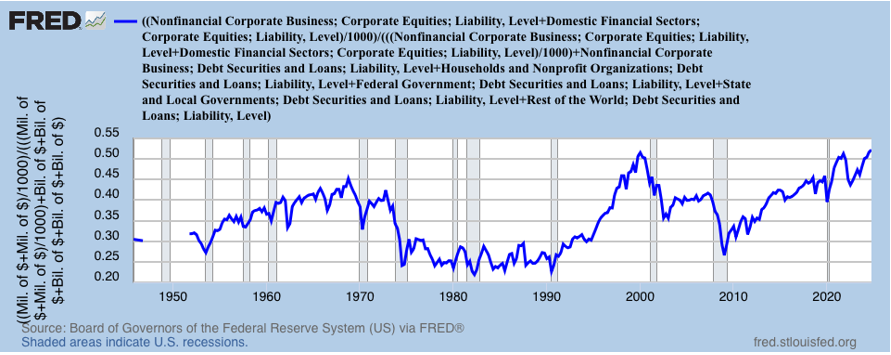

And that may still not be bearish enough. Scenarios in which the S&P 500 trades below 3,000 cannot be ruled out, even if it may seem unlikely. Consider that, per the best long-run forecasting model of stock returns, the market coming into 2025 is the most expensive market in the post-World War II era. With an R-squared in the 90s, this methodology projects negative returns over the next ten years. Levels of this magnitude precede massive shocks and/or recessions (the Nixon shock, the Tech Bubble, the GFC, etc). that bring it closer to long-run averages. I can’t think of a better excuse to send this to more balanced levels than a rewiring of the global economic system, which is exactly what these tariffs (and the “brilliant” minds behind them) represent: A repudiation of open markets. A zero-sum approach to economics. The commodification of value. And the spurning of the dollar and the U.S. economy as the hub for the global economic order.

“The state of the world is completely in flux and has been radically changed…This is the biggest change in the environment that I’ve seen, probably in my career.” – Howard Marks, April 4, 2025.

When someone as experienced and prescient as Marks is telling you that this is not a “typical” bear market, that the drivers beneath it are historic in nature, it should make any and all investors reconsider what exactly they envision in a “left-tail” scenario.

Figure 11: Equity Allocations Have Never Been This Heavy

5. Recommended Reads and Listens