The Wooden Nickel is a collection of roughly a handful of recent topics that have caught our attention. Here you’ll find current, open-ended thoughts. We wish to use this piece as a way to think out loud in public rather than formal proclamations or projections.

In July of 2022, someone I know and greatly respect warned that the pain present in the prices of chip stocks would not be stopping and was going to take a turn for the worse. The previous shortages were turning into gluts. Orders were being cancelled. And the design firms of the world were going to have to eat the costs of reserving capacity at fab houses like TSMC and write down inventory.

A few days later, I held a call with two analysts from a bulge bracket firm covering the chip industry. They had just come back from a trip to Asia. We discussed Intel’s strategic (mis)positioning in A.I., what parts in the auto supply chain were most constrained, prospects for data center server growth in the coming years, and more. On a whim, at the end of the call, I asked them both, “Hey, what are you hearing about orders being cancelled at fabs?”

“I’m not hearing anyone cancelling orders,” one declared. “There aren’t any demand hiccups out there,” the other proclaimed.

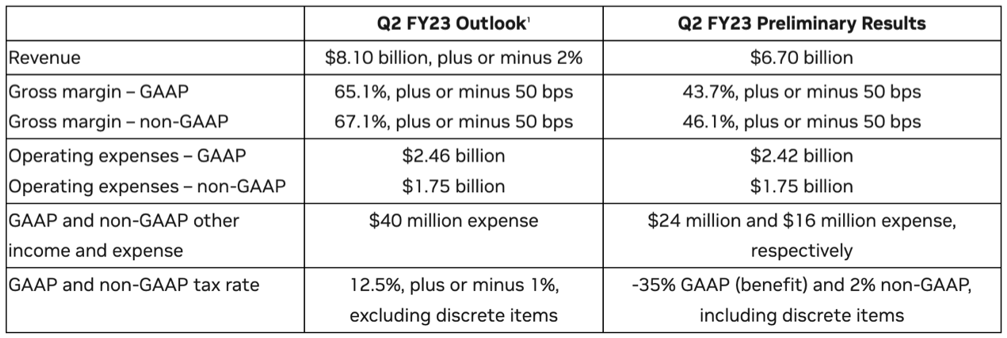

About two weeks later Nvidia published a press release stating that their forecast for the current quarter, made just 3 months prior, was going to be off by almost 20% and they would be writing down more than $1B worth of inventory. Gross Margins would drop over 20 points.

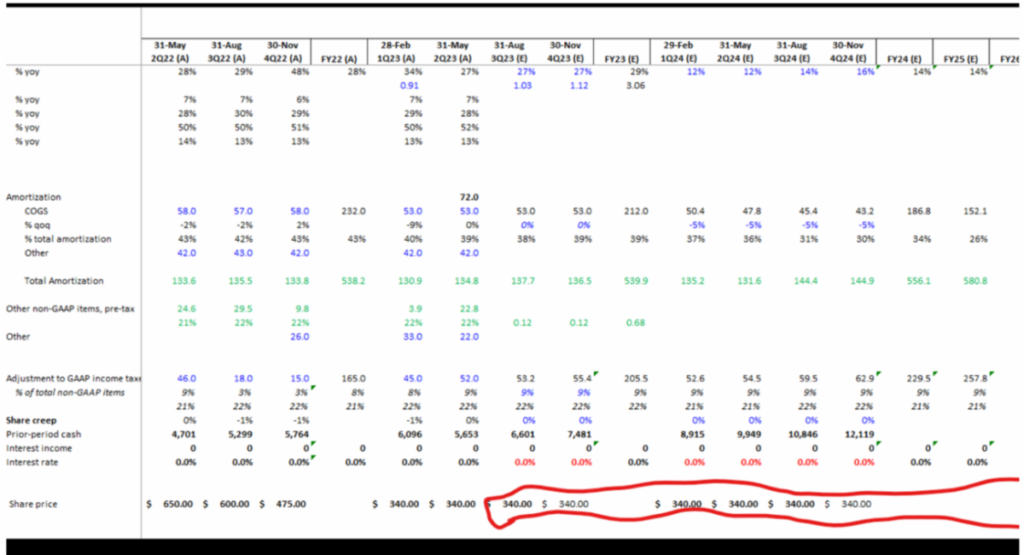

About a year later, while researching Adobe, another friend showed me an obvious problem in the assumptions modeled by another large bulge bracket firm.

The analyst had forecast that for the forthcoming year Adobe, a dutiful repurchaser of its shares, would be buying back shares on average at a price of $340. There was one problem. The stock was way above that price level and the analyst had a $500 price target no less, yet his estimate for the earnings that could be capitalized was way off. If you manually corrected it, then EPS would have to decline by over 10%.

We consume a lot of research every day; most days the only thing we do is read and think. We can, and want to attest, that these examples are both outliers of what to expect from the research arms of Wall Street’s biggest banks. But we increasingly find investors (especially young ones) do not understand what they’re consuming when they’re engaging in the research that drives headlines and moves stocks each day.

Like any resource, there is a healthy and unhealthy way to consume sell-side research. Analysts are often extremely bright, able to retain a broad and deep well of information, have access to unique resources, and can pass along views that a consumer may not be privy to. But when strong attributes collide with unproductive incentives, it’s usually the latter that wins, hence Munger’s well-known quote “Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome.”

What follows are some basic observations on how and why sell-side research can introduce more noise than it seeks to dispel. If these are obvious to you, wonderful, but you may be surprised to find the number of investors who rely on these resources as a crutch. None of what follows is a disparagement against analysts as a group or their practice. Again, there’s a good way and bad way to engage with this resource, but if you don’t know its shortcomings and tendencies, you’ll find yourself lost in the crowd and drowned out by the noise.

1. Conflicted Loyalties

First, from a first principles perspective, sell-side equity research analysts are not in the business of serving investors. Doing so is a means to an end. Equity research, within the large Wall Street banks, is a giant cost center. The research reports that make headlines and move stocks (like this recent one on A.I.) do not generate income for the firms that produce them. That’s the case even though a lot of work goes into these reports with large staff counts, long hours, proprietary data sets, and other costly inputs. Wall Street research is largely commoditized and fungible; analysts move between firms over the years, and dozens of analysts cover the same management teams, getting the same information repeated over and over again.

Sell-side research exists, mostly, as a marketing arm. By generating investor interest and connecting investors with management analysts, they keep their employer’s banking units in the running to win the next deal underwriting debt issuances, equity raises, or advising on M&A transactions. These activities generate the real business for Wall Street banks. Raising capital, M&A advisory, and trading generate billions each quarter but to generate that business there has to be interest in the securities. Equity research is a means to an end: they have access to clients/investors whose management teams will support their stock. The bank curries favor with management. It’s a distorted incentive at work.

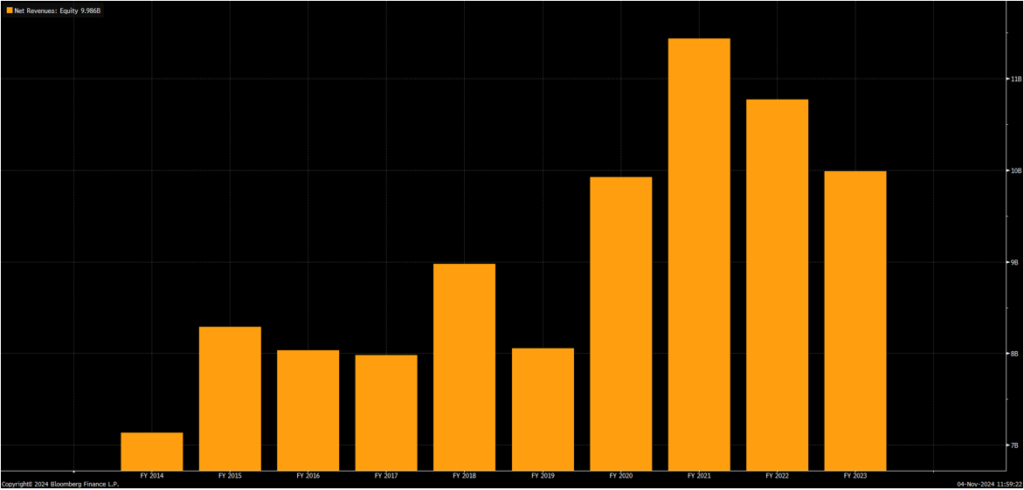

Further, equity research drums up trading activity in a stock. This is the other way banks generate substantial business and is an additional distorted incentive. Morgan Stanley generated $10B in trading equities last year alone, almost 20% of their entire business.

Figure 1: Morgan Stanley’s Equity Trading Revenues

All of this encourages herding and groupthink by telling people what they want to hear. To please management teams (in order to win banking business), equity recommendations rarely get “Sell” or “Underweight” ratings. Estimates for growth, profitability, and earnings hover close to what management has disclosed publicly because veering too far off the course either A) upsets management with negative outlooks or B) puts management in a tough position of meeting sky-high expectations. The result is research with “insights” that hover around general expectations. Just look at Microsoft’s most recent quarter. The entire distribution of estimates for the company’s reported revenue was within 4% of each other, between $64B and $66.8B. Stock prices may be deterministic at any given time but embedded within them is a probabilistic distribution of the future. With groupthink like this, a 4% deviation is immaterial and to an investor ultimately unhelpful.

This isn’t because of nefarious or devious conniving on the part of analysts but rather the product of incentives that overwhelm even the best intentions either consciously or subconsciously.

2. Short Termism

Like most of the investment apparatus, sell-side analysts fall prey and contribute to excessive short termism when evaluating individual stocks and the market as a whole. For most analysts, the primary consumer and user of their services is not a long-term investor (like a pension fund or an endowment) but rather the hedge fund community, who live and die on positions by the month and quarter rather than years. What they lack in time horizon they try to make up for with precision through the use of data, research, hustle, and expertise (and some leverage of course).

Many hedge fund analysts and investors are exceptionally intelligent. They know what proportion of the Cost of Goods Sold for Hormel’s guacamole joint venture is made up of avocados and how that will impact earnings due in a couple of weeks even assuming some proportion is hedged and after taking into account the split ownership structure. They can tell you about the seasonal patterns in stock grants at a software company and how that will inflate Non-GAAP numbers. When your business model is predicated on levering up extra pennies found here and there, you have to (try) know everything; it’s no wonder so many miss the forest for the trees. And using analysts to plug in holes, get access to management, and model different scenarios in the future, is part of the process. They are, in essence, a great customer for a firm incentivized via volume and turnover rather than results.

The constant time demand of Hedge Fund attention on sell-side analysts has circular effects. Information flows both ways: from analyst to funds and vice versa; it’s all part of the price and information discovery process. But if the information and data that hedge funds traffic in is overwhelmingly short term in nature it pushes the analyst in the same direction. Constant exposure to not just one set of ideas but one mode of thinking starts to seep in and reinforce the analyst’s prerogative to think near-term.

Again, incentives play a powerful role here. The Institutional Investor Magazine (II) polls investors each year and publishes a ranking for the best analysts and strategists on Wall Street. The output can have an enormous impact on an analyst’s career trajectory and compensation. One well-known firm was known for telling its new analysts that if they weren’t ranked first or second in their field within two years they could count on being let go. And how are II results tabulated? By weighing towards commission dollars, i.e. who trades the most. And when it comes to how they vote, Hedge Funds are like any other group, they don’t necessarily go for the person with the best track record but who is the most useful resource. It’s all circular and it distracts from the stated intention of finding value.

3. Price Targets

The notorious price target is yet another product of herding and distorted incentives. First, it is not an estimate of the intrinsic value of the business. It is an approximation of what a stock will trade at some point in the future; it literally invites the greater fool theory into the picture. Anyone who has ever seen any period of excess or fear in markets can recognize that price and value are two distinct things.

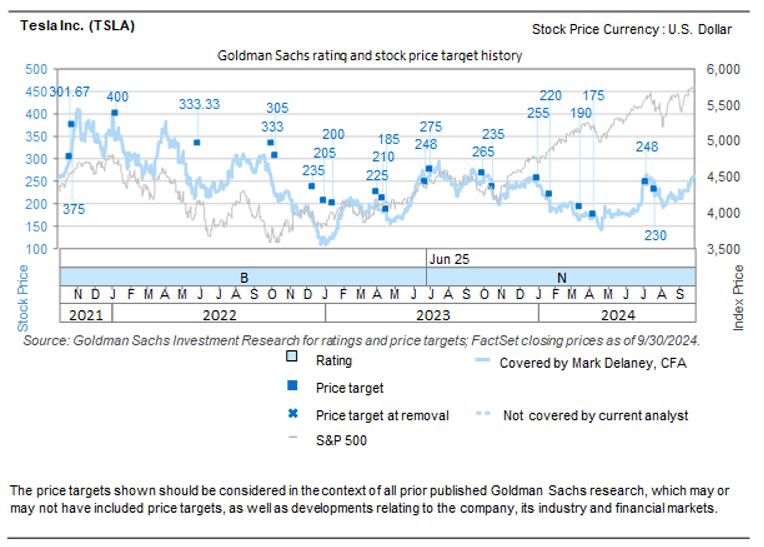

There is disproportionate credibility and career risk for analysts who are too offside a stock’s market price and the price target. Stocks gripped by a powerful narrative or lifted high by the market can easily move prices beyond analyst forecasts. Rather than look foolish, price targets set by analysts are often made in reaction to a price move that has already happened (you can see for yourself here). It invites some very creative valuation methodologies if we’re being generous.

Figure 2: Price Targets Follow Price Movements

4. Buy Ratings

Research analysts don’t exist in the same universe as most investors and as a result, don’t think about the world in a remotely similar way. One look at their coverage universe should help explain why. Analysts are solely concerned with a restricted and specialized list of stocks to cover; one person can only know so much after all. Rarely do two analysts cover the same list of stocks.

While this results in a deep, but narrow, knowledge base it leads to recommendations that are misleading. The “Buy” ratings you see and read are recommendations only against the rest of the analyst’s group of stocks they monitor. It’s not against the market as a whole. It’s not even against the entire sector.

What good is advice when one party considers a world that has 14 alternatives when you have hundreds if not thousands of other possible alternatives? On average, in a typical year, only ~5% of stocks get “Sell” ratings (for the obvious reasons mentioned earlier….it’s hard to curry favor with management when you’re advising people to stay away from your shares). How helpful can ratings actually be?

5. Recommended Reads and Listens