The Wooden Nickel is a collection of roughly a handful of recent topics that have caught our attention. Here you’ll find current, open-ended thoughts. We wish to use this piece as a way to think out loud in public rather than formal proclamations or projections.

This edition will focus on the payments sector, outlining some basics that get overlooked or misstated, history, and with emphasis on the core rails that move data to enable money flow, Visa and Mastercard. We will also touch upon how recent innovations fit into the landscape.

1. The Economics of a Swipe

“I actually had no idea how complicated cards are. I thought Visa was just capturing that 3% of every transaction and that a few people were making exorbitant money.”

The quote above was an actual statement someone shared with us upon digging into the core payments infrastructure we’re all accustomed to and take for granted. It’s a sentiment that is expressed in some way once people start to peel back the layers of the payments system in the West, even to those who dedicate a lot of time to the space. There is a lot of complexity embedded into the financial payments system but the abstraction into simplicity is what has allowed for capital to become more abundant, merchants and vendors to increase their focus on what sets them apart, the economy to grow and for some great investment returns along the way.

Figure 1: Since Going Public Mastercard (White) and Visa (Orange) Have Trounced The Indices

One of the biggest points of misunderstanding is the level of fees embedded in a transaction, who earns them, and what’s involved. In the simplest form of a swiped transaction, there are at minimum 5 parties involved: the consumer, the merchant or vendor selling goods or services, the Merchant Acquirer, the bank that issues the card, and the networks which coordinate the flow of information with the largest being Visa and Mastercard. For every $100 of sales, the merchant keeps roughly $97.50. The remaining $2.50 (called interchange) gets split among the other parties with Issuers/Banks taking ~$1.75, Acquirers (banks and other firms that connect merchants into the payment and banking ecosystem) taking approximately $0.60, and the networks taking the smallest cut, roughly $0.15, and just pennies on a debit transaction.

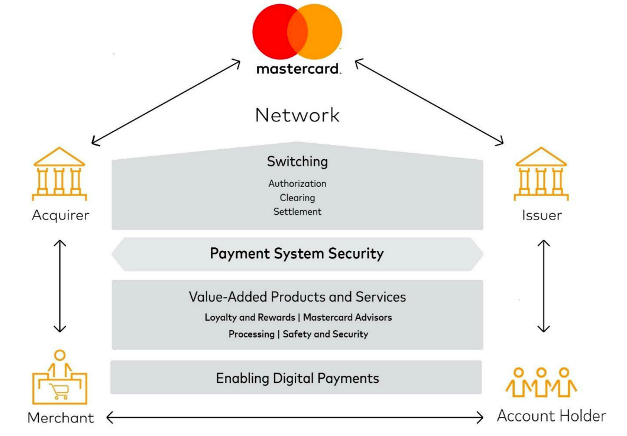

Figure 2: A Simplified Image of the Payments System

And thus the first of many myths gets dispelled: that the fees collected by the networks/rails represent a leech imposed on the payments system. In reality, for the cost of a few nickels a consumer has access to over 170 million merchants around the globe and that merchant, in turn, can rest assured that prospective customers are good for their money, regardless of currency, just by the plastic they carry without ever having to do a credit check or have a bookkeeping operation in their back office to track receivables as retailers did generations ago.

So where does the angst, from pieces like this, come from? Blame some mix of ignorance, stubbornness to learn how things work, and to think.

Failure to separate banking problems from payments: currently bundled together. Problems of equal access to credit, and comprehensive risk scoring, are different from how we buy groceries and electronics.

2. Animosity and Paradoxes

Despite 50+ years worth of technical investment, new standards and innovations, and reduced friction in payment flows year after year pieces like this get published or skirmishes between major retailers, and one of the networks becomes public knowledge, such as here. Why? First, the simplest explanation is that the financial press frequently fails to provide a full picture of the financial landscape, including the number of parties that enable the payments plumbing to work as it does and that the core networks take by far the lowest piece. Second, this is where what looks like a simple flow in Figure 2 belies a lot of work done along the way and in a short period of time. In a fraction of a second with each swipe of a card, Visa and Mastercard analyze over 500 points of data specific to the proposed transaction, authorize the user, clear the transaction, verify funding, and settle payment. But getting here required decades of investment and the cumulative knowledge that comes along the way. Third, the largest portions of that capital investment were done decades ago to build the ground floors of a payment environment. Incremental investment has gone towards creating new, incremental plumbing to connect to core banking products, continuously improving fraud rates, and developing analytics and other value-added services but the largest dollars have been spent and depreciated. Moreover, the technology is extremely scalable; the tech required to process one payment across a variety of banking channels is largely similar to the tech necessary to process one million. But the incremental revenues fall to the bottom line. After some amount of time (decades in this case), it’s unsurprising then just by virtue of mathematics that Mastercard and Visa post Operating Margins north of 50% and 60%. But simply seeing those figures on their face fails to consider the context that the investment was done over decades to enable where we are today. Rather than take the time to understand the system it has been cheaper for many to cry foul.

Fourth, and this is more anecdotal than anything, there is a repeated failure to separate the payments system from the banking system. The latter has been a source of tremendous pain in the not too recent past for a lot of people and still fails to be a more holistic force of financial intermediation. The former however is tremendously efficient. No one in the developed world has ever walked into a store and left without their goods or services due to their payment methods not being accepted or based on where they bank. It just doesn’t happen. And that is the product of decades of investment.

Fifth, skirmishes that go public between a major retailer and the payments system are frequently just public posturing as part of a negotiation. Do retailers really care about the 2.5% they give back to the payments network when they’ll give you 5% back on your purchase just for using their credit card like Target and Amazon do? Is the 1.5% that a bank makes on a transaction for taking on credit risk and underwriting a consumer prohibitive to a retailer when they’ll turn around and agree to give 8% to Buy-Now-Pay-Later services like Affirm and Afterpay? How do these paradoxes add up? Arrangements like these are not uncommon and strike many as inconsistent positions but in fact, they’re not mutually exclusive.

Like other examples throughout commercial transactions, volume discounts exist in the payments world and massive retailers like Kroger or Walmart do get different rates from both card networks than what is “average.” One reason is due to the sheer volume of transactions they bring. But a second is that large retailers have become massive repositories of data on customers, SKUs, promotional events, marketing effectiveness, and more. And as their data advantage has gotten larger, they’ve been able to do some level of customer underwriting in-house. Hence why Target is willing to give you 5% back on purchases; they want the data for marketing and advertising purposes. There’s an old saying in marketing departments that 50% of ad budgets go to waste but that no one knows which 50%. When retailers offer up lucrative cash-back programs or hold out from a card network’s system it’s often to acquire more data on customers and transactions to tilt that 50/50 proposition more to their own advantage.

3. Regulation

Despite a lot of misconceptions about payments and hypocritical statements from the retail industry, the sheer massive size of consumer expenditures in developed economies will always gain attention from politicians and regulators. And with the financial sector in the cross hairs immediately after the GFC regulators set their sights on the debit card market in the U.S., came the Durbin Amendment in 2011. The act put a price cap on how much the major networks could charge on a debit card transaction to 5bps plus a $0.21 fixed fee per transaction. The cap represented a cut of 45% to debit card rates. The belief by Senator Durbin, and others, was that by cutting debit card rates retailers would drive down the price of goods and services in a race for market share, lowering prices for consumers. Rates indeed came down, and yet the regulation overall is widely regarded as a massive failure and a regressive one at that.

Figure 3: Debit Rates Post Durbin Amendment, Source: American Bankers Assocation

While transaction rates fell, an analysis by the Federal Reserve found that only 1% of merchants lowered prices, 77% kept prices flat and the rest raised prices despite the lower processing fees. Acquiring banks did not pass along fee reductions, pocketing the lower processing fees as pure margin. On the banking side, an analysis from the University of Pennsylvania found that banks made up for the lost revenue by imposing account minimums, lowering interest rates on deposits, and implementing other fees that were borne by the poor more than other economic classes.

The card networks saw no impact to their volumes despite the legislation. In fact, their market share grew as a result of the price cap as it drove out more inefficient alternatives and because at their core both Visa and Mastercard have become extremely efficient in running their networks.

On the whole, efforts to siphon profitability out of the payment ecosystem have been like a game of whack-a-mole: knocking down one issue makes another one pop up somewhere else.

4. Appreciating Moats and Alternative Payment Methods

There are currently only 3 countries in the world that do not regulate credit card rates in some form: Russia, Japan, and the United States. Every single other country caps rates one way or another and for varying reasons: to combat fears of market power concentration (as is the case in the EU which has failed spectacularly) to encourage digital payments and get rid of cash in developing economies so as to cut down on fraud and black market activities. In many cases, payment schemes have become nationalized, open to all and free to use. And in every single market the story remains the same: the two dominant card networks grow share of payments volume. Some may call that a moat.

But analysts, journalists, and investors frequently misplace the exact source of the moat, often wanting to place it on a singular element. Most place it on the sheer number of nodes connected into the network: Visa has close to 4 billion credentials alone on their network. And while duplicating this effort would be enormously laborious and time consuming (especially when your reward is less than 20 cents), it is not impossible or prohibitive from a pure technological perspective. But to even get to that point there is the chicken and egg problem: how do you get thousands upon thousands of banks to open up their connections if you do not have consumers to offer as customers? How do you get consumers if you do not have banking connections or merchants signed up on your platform? What incentive is there for them to join when what they have works so well, providing instant access to hundreds of millions of merchants regardless of where they bank across the globe? And even if you start to accumulate customers and merchants and banks what are the odds your underwriting of fraud will be better than two networks who have been at it for 50+ years and update their risk models with billions of transactions each year? What is the probability you can simultaneously develop a set of APIs after all this to accommodate all the use cases that continue to flow out of digitized payments: from “push” payments, to tokenization, to cloud processing, to virtual cards, and so forth?

The moat for the card networks and the reason they have been incredible investments that people continue to misunderstand is a shared economic model for investment. Participating in the networks run by Visa and Mastercard obligate all parties to a clear set of rules, standards, processes and procedures and everyone knows where they stand and what is expected of them. Identity verification, trust, risk, ownership of fraud, and means of recourse are all embedded into the DNA of the current payment rails and their participants. But what the shared model also offers is a clear outline of what each party stands to gain by participating and investing in the model.

It is this latter piece that is missing from Europe’s long delayed open banking initiative, PSD2, and why uptake has been incredibly weak with bleak prospects despite compliance. But it’s not the only initiative that keeps running into the wall. Huge attention has been given to whether real-time payment schemes, Account 2 Account payments, or crypto projects could decimate or disrupt the business model of the major card networks, but analysis and energy dedicated to these alternative means don’t overcome the most basic hurdles posed throughout this piece:

- By in large, there is no problem consumers have in paying for goods and services with electronic forms of payment. 90% of electronic payments occur in the top 10 markets, countries where financial and legal infrastructure are readily established. None of us visit a merchant and fail to leave with our goods due to failure of payment. Thus, the hurdle for a new payment scheme is quite high.

- Real time payments do not provide any incentive or benefit to consumers. It makes no difference to me when checking out at a store what the settlement process is behind the scenes. I swipe my card and in a fraction of a second my payment is approved. If there is real-time infrastructure behind the scenes my experience doesn’t change in the slightest. If my experience doesn’t change, then there is no reason for anyone to invest behind this method for consumer payments (business to business payments are a different story entirely).

- Further, real-time payments offer no protection against fraud (see here). What incentive do customers have to use Zelle, or other real-time products, if there is even the slightest change of fraud and there is no recourse for recovery?

- The networks are remarkably efficient: operating at between 3 and 8bps in markets where real-time infrastructure is available. Why replace something that works so well and at such a low cost? In these markets, they have never lost share given the trust financial institutions, merchants, and consumers have in the system. Volumes processed over the card networks grows as access to any electronic form of transaction grows; moving more and more people into the banking system, regardless of initial instrument, is a rising tide that lifts all boats

- National payment schemes, like those in Brazil or in India, lack scale, unable to communicate with services hosted beyond their borders. While enormously successful in helping to minimize the number of unbanked there are limitations to adoption and use cases.

- Leaving the very long list of instances of fraud and deceit, crypto as a means of payment suffers many of the same chicken and egg type problems. There is no inherent consumer incentive to use crypto tokens to pay for groceries or their heating bill. Transaction costs can vary widely from one day to the next, the core technology behind Bitcoin does not scale efficiently by design, and there is no mechanism for reversing transactions due to fraud or other valid reasons.

- Imagine using Schwab’s Debit Card for every day payments, but instead of debiting cash from your checking account it sells a fraction of a share of Apple stock to pay for a meal at a restaurant. That’s a parallel to using crypto as a consumer payments alternative and yet no one asks for such a product despite the technology being available. Why? Because it does nothing to make the purchase experience better, more convenient, faster, more secure, etc.

- Crypto development is better off focusing on use cases where the technology is creating value in new ways rather than trying to duplicate a system that is cheaper, faster, secure and more scalable and ubiquitous.

- The growth of payments services like online gateways, payment facilitators, peer to peer transactions, mobile wallets, virtual cards, and others demonstrate the stickiness of the core networks. All these innovations were made possible by plugging into the existing network and infrastructure provided by Visa and Mastercard and building on top. Much like the core cloud providers abstracted away key infrastructure demands that enabled the cloud computing and SaaS explosion, the core payments rails, by virtue of their low cost and easy accessibility, enable innovation, new services and business models by functioning as the lowest common service for everyone to build on. Rather than compete with Visa and Mastercard, these services found it far easier and more lucrative to partner into an existing, functional ecosystem. A competing system would have to duplicate and supersede this functionality.

What looks like a simple swipe at the grocery store by no means is an easy transaction. We hope this edition cleared up some misconceptions, provided clarity on some present issues and headlines, and explained why the digital payments space has been a source of tremendous value for all parties involved.

A special thank you to Tom Noyes and David Kim for their writings and analysis on the space that has helped educate us for a number of years.