The Wooden Nickel is a collection of roughly a handful of recent topics that have caught our attention. This week we are focusing specifically on Intel given recent developments. Here you’ll find current, open-ended thoughts. We wish to use this piece as a way to think out loud in public rather than formal proclamations or projections.

1. Where Do We Go From Here?

Intel’s most recent and disastrous quarterly earnings report sparked a lot of attention and commentary, justifiably so. But the hits kept coming long beyond earnings.

- First was the news that one of the few technically adept board members (and a legendary CEO within the tech sector) was resigning. Reading between the lines, the resignation looks like a protest of the company’s strategy, operations, and leadership.

- Next came the news that the company’s manufacturing arm, the business upon which the future of Intel rests, was suffering serious setbacks with customers.

- Then came reports that Intel was meeting with bankers and considering drastic actions to save the company from selling off fledgling businesses to spinning out its manufacturing business.

The latter was the most concerning to a lot of people. It had the smell of a move that was “breaking glass in case of emergency.” For context, people have certainly speculated that Intel’s joint chip design and manufacturing model had an expiration date. But this was more of a 2030 story in some people’s mind: Not 2024. To consider that, even remotely, signaled that something dire must really be going on. As one sell-side analyst put it, if it wasn’t for the Chips Act we’d be talking about going-concern questions here.

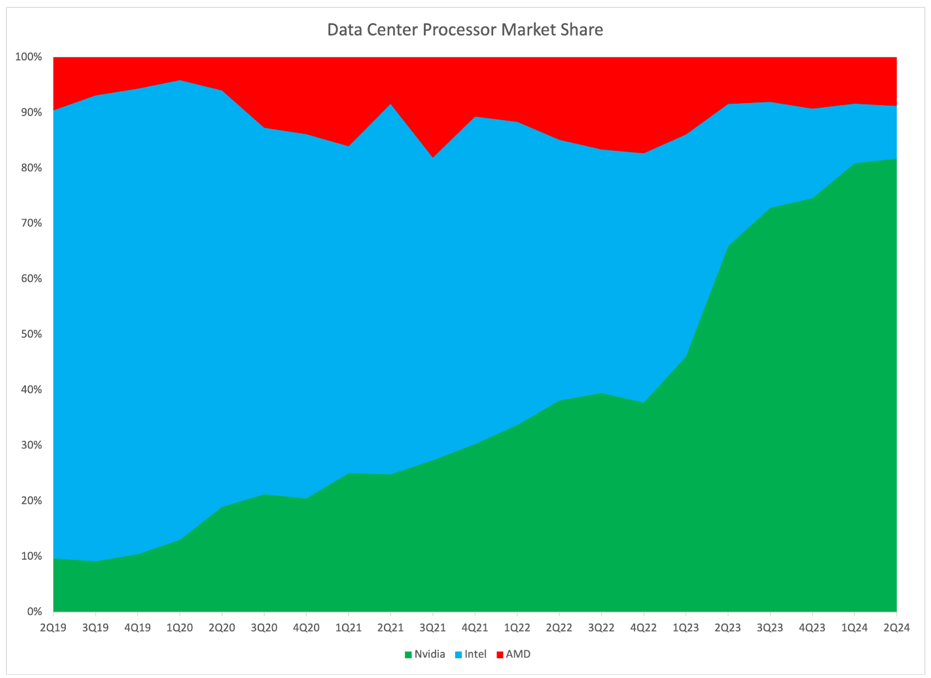

Others have written plenty on the weak state of things revealed by the most recent set of financials, so we won’t spend much time here rehashing those things. We would point out, however, that quarters like the most recent one are not necessarily the product of actions in the past 3 months or even the past year. In the case of Intel and in the world of semiconductors, the outcomes we’re seeing now were prepped many, many years ago. For instance, Figure 1 lays out one estimate of the shift in market share for data center chips in the last five years. Notice that even before AI and ChatGPT made Nvidia GPUs the most desired technology on the planet, things were unwinding for Intel and doing so quickly.

Figure 1: Intel’s Lost Market Share in Data Center, Source: Jay Goldberg

For people who were watching closely the chance that periods like the last couple of months would come, this was acknowledged as a real possibility although seeing it play out in reality still has some shock value. After all, this isn’t just any tech company but one that possessed one of the most dominant technological and economic stretches in corporate history, which was essentially the face of a new era and is interwoven with national success in many dimensions. This is tech’s GE, though importantly without financial fraud.

Things started unraveling for Intel long before this most recent quarter and long before large language models as well. The chip landscape specifically, and technology in general, is undergoing tectonic shifts in where value structures ever since Moore’s Law started dying. It’s made Intel’s errors all the more painful some of which include:

- Passing on supplying chips for Apple’s iPhone and declining to manufacture those chips.

- Relying on older equipment longer than necessary to save money rather than investing in things like EUV.

- Delaying product roadmaps time and again.

- An unhealthy addiction to milking their core cash cow rather than investing in new product types, Arm-based processors, and GPUs (causing them to miss the AI boom).

- Inadequate internal investment while spending tens of billions in buybacks and dividends.

2. “Culture Eats Strategy for Breakfast”

If there’s one angle to the current chapter of the Intel story that I wish was emphasized a bit more would be the role of culture. Culture is not a topic that a lot of the financial industry writes about, and it’s understandable to a degree. Defining an amorphous variable like culture can be difficult and fungible from one party to the next. Often, evaluating a corporate culture only happens when one of two tail events occurs: things either went really well or really poorly.

Culture might be one of the most difficult things to assess within a business from the outside looking in. For most, it’s not relevant; our holding periods are too short, resources too scarce, or there is lower hanging fruit to catalyze a stock. Further, cultures, like many other things in life, do not exist in a binary vacuum but rather on a spectrum with most somewhere between two extremes, and subjectivity in its assessment is another complicating factor.

But if there’s one thing that the current Intel debacle reminds us of is that culture transcends management teams, board members, and even technological eras. Hence the difficulties in rooting out a poor one. The strategic mistakes listed earlier occurred across multiple CEOs and long before things like Large Language Models were in our regular discourse. Companies can survive strategic missteps in one way or another. The fact that the seeds of Intel’s current predicament occurred over such a prolonged period and with such changes in the technological landscape makes things all the more depressing and frustrating because each of those potential pivot points offered a chance to make things right or get on the right side of the competitive landscape. The fact that mistakes compounded instead of sparking a new course is all the more evidence that something bigger than just a poor management team is at the helm or that the board lacks technical expertise. It’s the evidence that a broken culture existed.

When Gelsinger announced Intel’s new strategic direction about three years ago, he put Intel’s future squarely in the service industry. Chip-making is a lot more collaborative of an endeavor than most realize. The sheer engineering challenges in pushing beyond Moore’s Law demand that the various parts of the semi-value chain coalesce around standards and realize the interconnected nature of success and value creation. There can’t be the Intel way anymore with its own set of proprietary tools, software, modifications to equipment, and other insular techniques; it had to realize it was part of a larger ecosystem. Going down the road of trying to win, by merit, the manufacturing step from peer designers, including competitors, was the best indication to date that the firm understood some sort of reset was needed.

None of this may ultimately matter for Intel; it is unlikely to recapture a semblance of its former glory. The strategic and financial setbacks may overwhelm them. But I bring up the Intel example because many a “value” investor has tried and failed to get into Intel thinking the worst was behind them. Yes, there were moments to buy and sell here but the fact of the matter is that in the time between it first made chips to go into Apple laptops (2006) and ChatGPT (2022), revenues essentially doubled but operating profits between then and now have declined over 80% (from around $6B to $1B if we’re being generous with 2024). Buffett has often remarked that when a skilled manager links up with a lousy business it’s the latter that wins. I think the same can be said for a lousy culture.

3. Chips Act: Days Late and Dollars Short?

Intel has been the biggest winner of funds from the Chips Act that Congress passed during the peak of the chip shortage. So what do its recent stumbles mean for that allocation of money?

To be honest, we don’t know and no one really does. Cash has not been sent out the door, a fact that the Commerce Department finds itself needing to constantly remind people of. While awards have been decided, the actual outflow of cash is dependent upon multiple stages of criteria being met. So, in all likelihood, it has no real bearing on the awards as they’re gated by manufacturing progress anyway.

The Chips Act had multiple goals embedded in it, such as narrowing the cost gap with manufacturing chips in the US versus East Asia, building up an ecosystem and full supply chain instead of just manufacturing, and making sure that the US has access to leading-edge chip supply for defense needs if nothing else. While these are in some ways interrelated, we do worry that trying to accomplish a number of different goals through one vehicle could present some difficulty.

For one, consider that while $50B is being allocated for manufacturing investments between now and 2030, TSMC will spend $30B-$40B per year. Capital investments in chip making aren’t just about capacity additions but are also in many ways R&D expenditures. The $10-$15B that Intel could get may be plugging a leaky bucket. Are we sure the current budgeted amount is enough? Is there appetite or willpower for more? My guess is no and if not, then what is the goal of the initiative? Is national security at stake or not? If so, we may need to consider that down the line more funds are going to be needed and probably some other structural reforms as well. If not, is this just a commercial initiative (we remain skeptical)? If Intel fails (however you define failure), what’s Plan B?

The answers to those and other pertinent questions will be years in the making, much like Intel’s turnaround.

4. Recommended Reads and Listens