The Wooden Nickel

The Wooden Nickel

-

Author : The BlackSummit Team

Date : August 23, 2022

The Wooden Nickel is a collection of roughly a handful of recent topics that have caught our attention. Here you’ll find current, open-ended thoughts. We wish to use this piece as a way to think out loud in public rather than formal proclamations or projections.

- A Consumer Checkup

The vitality of the consumer has been the subject of a lot of angst so far this calendar year. Higher prices for everything, especially food and energy, in the backdrop of a slowing (but not recessionary) economy have led investors to believe that the consumer would pare back on spending, slowing the economy. These fears, manifested in places like the smartphone market or the financials of Walmart and Target, have pressured the consumer sector as a whole. Year to date, Consumer Discretionary stocks are the second-worst group in the S&P 500 behind only the Communication Services sector, also beset by a weak consumer given the group’s ties to advertising spend.

With retail sales and overall consumption activity still being healthy contributors to GDP growth through the first half of the year, the above-mentioned headwinds have led to some consternation and alarmism on credit card debt levels.

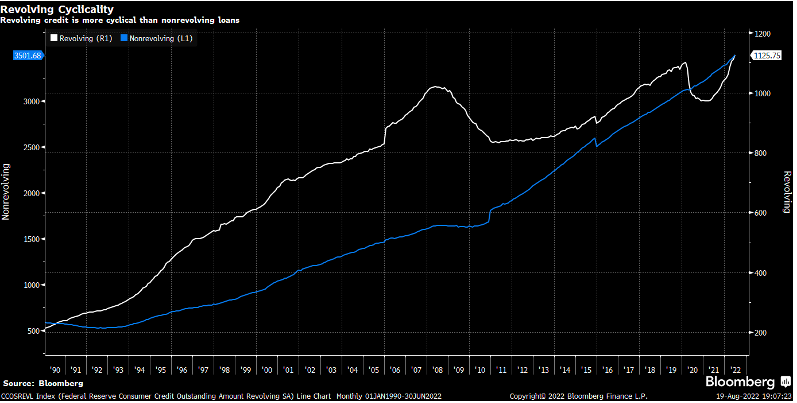

While credit card debt has hit new highs this cycle (Figure 1), gross levels of debt that have been reported severely lack context.

Figure 1: Credit Card Spending Has Accelerated This Cycle

For one, data on general consumer credit fails to delineate between credit that is fixed (like a mortgage or car loan) with that that is more cyclical like credit card debt. A simple breakdown shows that the latter is just now recovering to pre-pandemic levels (Figure 2). Given that the last year or so has been the strongest for labor in decades, the capacity for consumers to carry this debt is far better. Rather, it’s been the strong demand for things like housing in the last two years that has boosted debt balances and the creditworthiness of a typical mortgage borrower is much stronger this cycle than in years past (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Revolving Credit Is Just Now Reaching Pre-Pandemic Levels

Figure 3: Mortgage Originations by Credit Score, Source: Bill McBride

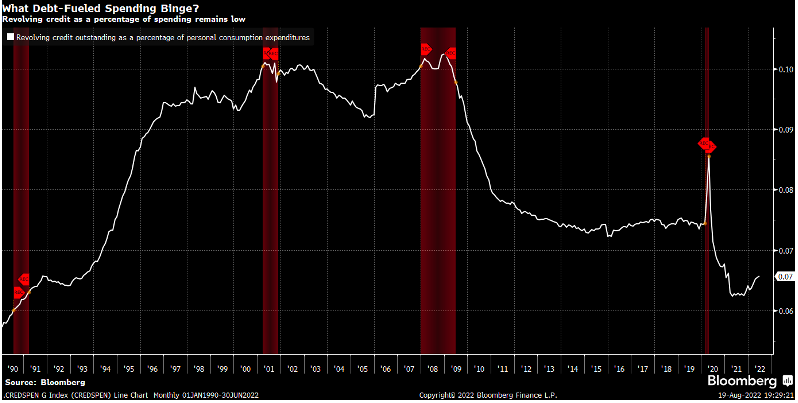

Finally, it should be obvious that with prices at such high levels for two years in a row now inflation would be showing up in credit card balances as well. Thus, if consumers were stressed, whether by inflation or other factors, credit balances would be making a larger proportion of their consumption. That is simply nowhere near the case (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Credit Spending as a Proportion of Total Consumption, Source: Cameron Crise

2. Alternative Market Views

It’s one thing for people to pontificate on what they think will happen in asset markets and quite another to put their foot forward with some skin in the game. There’s plenty of value in the former but special attention should be paid when people vote with their wallets, especially when some semblance of conviction can be parsed out from pricing discrepancies across markets, products, or positioning that is inconsistent with price activity.

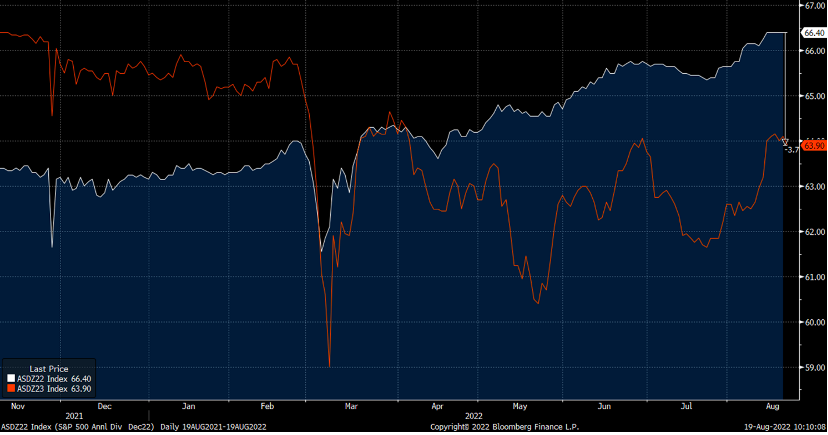

With more and more investors verbally stating they expect a recession over the coming year there is some evidence of this getting priced into equity markets. Dividend futures markets are presently pricing in some form of recession for 2023. Futures contracts for dividends from the S&P 500 to be paid out in 2023 are currently projected to fall around 4% from 2022 (Figure 5). Based on history, investors are expecting a relatively mild recession, one more in line with the fallout from the dot-com bust when payouts fell around 6% than the Global Financial Crisis when they fell by about 25% (Figure 6).

Figure 5: 2023 Dividends (Orange) Projected to Decline ~4% From 2022 (White)

Figure 6: S&P 500 Dividends per Share (Blue, Left Axis) and YoY Growth (Red, Right Axis)

But looking out at what the bond market expects a year from now is quite puzzling. Figure 7 shows a chart of the shape of the yield curve from a few days ago in orange. In blue, you’ll see what futures markets expect the shape of the yield curve to look like by the end of June in 2023. In essence, the fixed income market expects both the level of interest rates and the shape of the curve to be unchanged for any duration beyond a year.

Figure 7: The Yield Curve Has No Idea What to Expect

The more likely explanation is that bond investors just have no clue what will transpire going forward. Who can blame them?

3. The Axiom That Just Won’t Die

We’ve written multiple times about the many ways in which generic classifications of stocks do more harm than good to investors (here, here, and here). The binary debate about “value” vs “growth” does more to obfuscate investment rationales than crystallize them. The labels and adages that flow from the debate frequently contradict themselves or don’t hold up after much critical scrutiny. Yet it will not go away and probably never will, but we still enjoy well-reasoned and thorough deconstructions of that rhetoric.

The most recent volley in the debate comes from Cliff Asness at AQR. We’ll let his words speak for themselves as he makes the case as convincingly as possible.

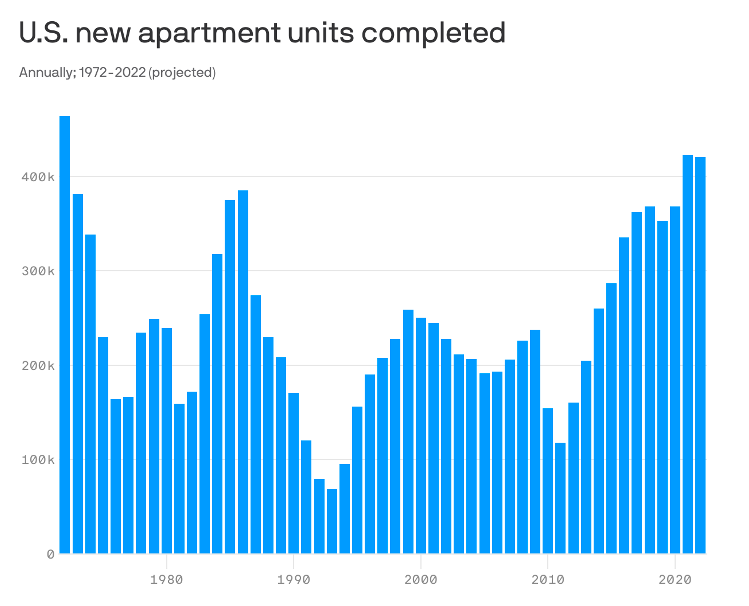

4. Shelter Relief

2021 was a historic year for multi-family housing. Over 400,000 units were completed in 2021 – the first time that mark had been breached in approximately 50 years. 2022 looks like it will be just as big. Considering that shelter-related costs make up approximately one-third of the Consumer Price Index, major development in this market can have repercussions on the general price level down the road.

Figure 8: Multifamily Construction is at Historic Levels, Source: Axios

But there is a bit of a chicken and egg problem when it comes to housing and the CPI. As Matthew Klein writes, housing tends to follow worker incomes. So will an increase in supply put downward pressure on rents, slowing the labor market’s demand and bargaining power for future wage increases? Or does labor have its own drivers that will push up rent demand regardless?

Figure 9: Housing Costs Move with Income Levels, Source: Matthew Klein

5. Prisoner’s Dilemma and Monetary Policy

A thought exercise for this final portion of the Wooden Nickel.

There’s this idea prevalent in the investment community that the Fed won’t continue with rate hikes if inflation remains elevated should the economy weaken even further. The argument rests on the FOMC not having the stomach to willfully enter a recession if that’s what it takes to kill off excess demand. After all, the taper tantrum roughly 10 years ago and the Repo-induced tightening in 2018 were examples of financial market volatility that turned Fed commentary more dovish, before any additional economic damage was done. If the Fed couldn’t do it then then why would we think they can do it now?

To that, two questions must be raised. First, how many Fed Chairmen have dealt with a recession? Second, how many have confronted serious inflation? The answer to the first question is every single one. The answer to the second question is two: one failed and one succeeded. The one who failed, Arthur Burns, may as well be a curse word in the annals of monetary policy history. The other is revered as the greatest leader the institution has seen.

So, if you were in the position which would you fear more: being the Burns of your generation or being another Fed Chair in the long list who oversaw a recession? Which one is more damaging to your legacy and the institution’s credibility? I’d argue the former. And I’d argue that it’s not particularly close.

People may like to armchair quarterback the head of the Federal Reserve, and there are plenty of legitimate reasons for doing so. But if someone makes the argument that rates can’t rise further based off of some sort of institutional behavioral history (and that argument is certainly being made), then I would retort to those people that they are basing that supposition on a sample size of exactly zero because there are no examples of a dovish pivot in the face of high inflation for more than 40 years. That’s not the pile of evidence I would want to rest my argument on.

There may be a dovish pivot in the future that puts rate hikes on pause. Maybe the inflation target gets raised from 2% to 3%. Maybe the Fed explicitly starts targeting Core inflation rather than headline. Maybe something else. But being right for the wrong reasons is the same as being wrong.