The Wooden Nickel is a collection of roughly a handful of recent topics that have caught our attention. Here, you’ll find current, open-ended thoughts. We wish to use this piece as a way to think out loud in public rather than make formal proclamations or projections.

1. A Narrative Is Not a Thesis

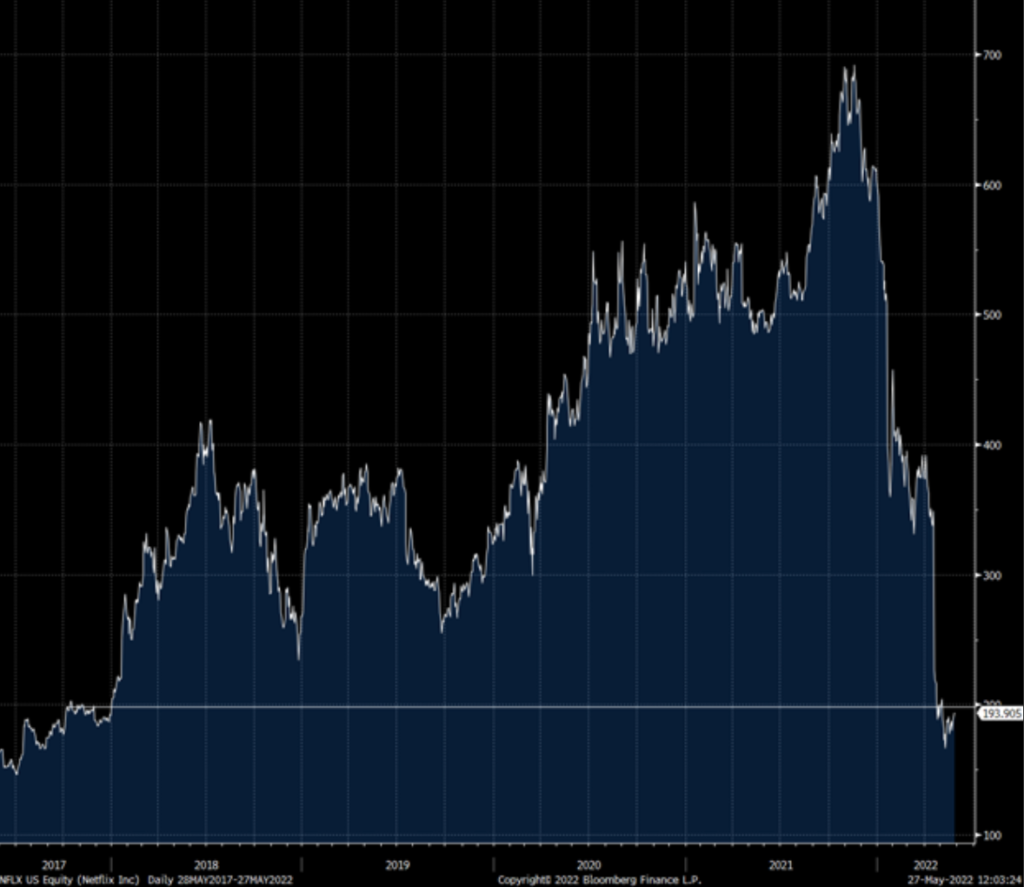

The majority of Q1 earnings have come and gone, some of them with a bang. Target’s stock plummeted 25% on bloated inventories, cost pressures and supply chain troubles. Walmart had its worst two-day sell-off since the Crash of 1987 noting a trade down in the consumer. The name that kick-started this volatile earnings season was Netflix, falling 35% after it reported earnings. The company saw shares fall 25% the prior quarter as well.

Netflix has now given up 5 years of gains in the span of just a few months.

Netflix’s earnings show the extreme dangers of investing at any price. Growth is not sufficient to justify an investment. “Disruption” isn’t enough to warrant an investment. The price you pay always matters. The gains shareholders experienced over the past five years have been wiped out. A narrative works until it doesn’t. They are far flimsier and more ephemeral than realized.

But this isn’t a Netflix- or streaming-driven phenomenon. EV stocks have been crushed. Battery makers have been crushed. Edge networking stocks decimated. SPACs. Gaming stocks. Fintech. The list goes on and on and they all have in common wild valuations that are based on nothing but dreams and rhetoric.

If the best case you can make for a stock is that “it will grow” or “will take share” then you don’t have much of a thesis at all.

2. Tapering Started Long Ago

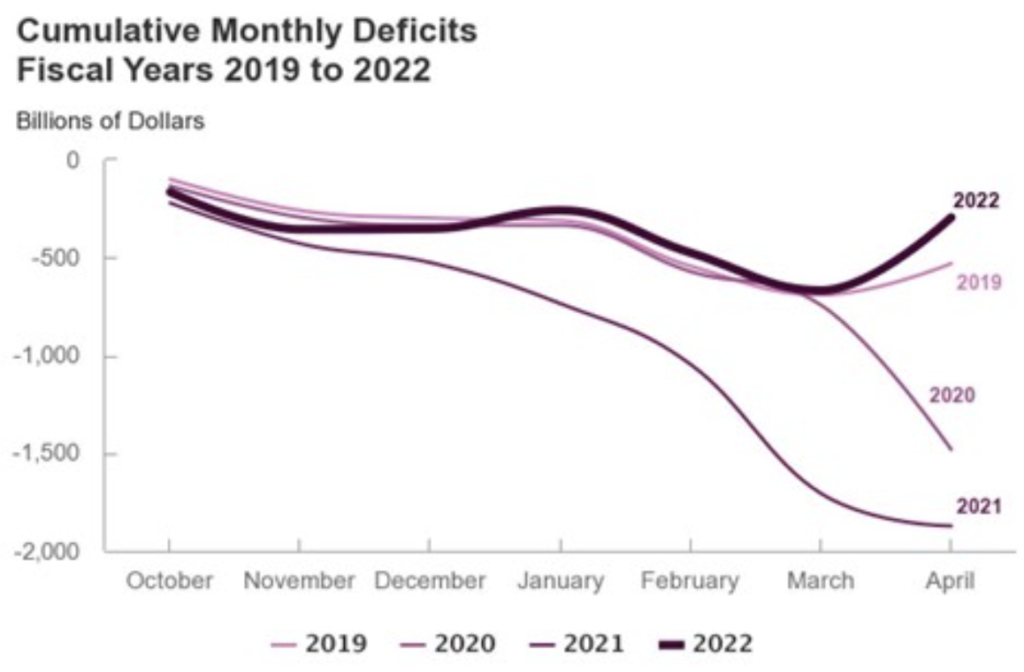

In the first seven months of fiscal 2022, the Federal Budget deficit has declined over 86% from the same period in 2021.

This is a massive belt tightening. For anyone familiar with the Kalecki-Levy identity, the consequences between a tighter federal purse and financial markets are clear and align nicely with the activity in asset prices so far this year.

3. Housing and Demographics

Financial markets can move much faster than official policy. Financial conditions are one such example of this phenomenon. High Yield spreads rose much higher and faster than official policy rates did in 2022. 30-year mortgage rates function in the same manner.

Figure 1: High Yield Spreads (Blue) and Mortgages (Orange)

Rate sensitive sectors, like housing, can give us a glimpse into the sort of macroeconomic environment in the near-term future. So far, a material slowing is apparent. Bill McBride writes:

“We are seeing a significant change in inventory, but no surge in new listings. This means the increase in inventory is due to a decrease in demand, likely because of higher mortgage rates.”

Figure 2: US Pending Home Sales Have Slowed Quickly, Axios

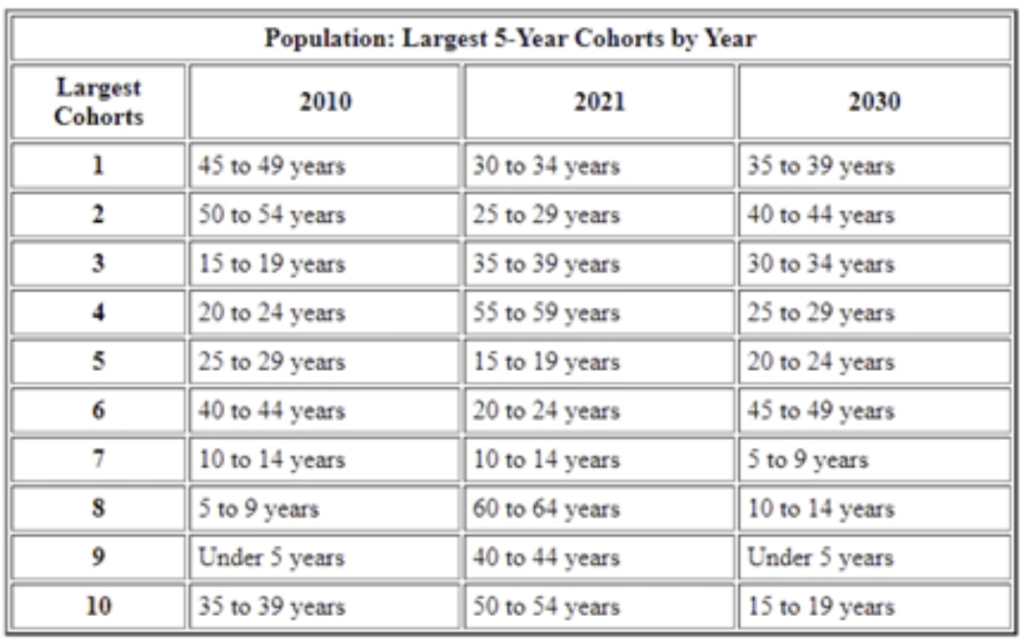

Whether or not mortgage rates resume higher or maintain these levels, the most powerful force in the housing market over long periods of time is demographics. Household formation follows population demographics and the tailwind for housing is not going away any time soon. The three most populous age cohorts as of 2021 are all in or very near prime home buying years.

Figure 3: Largest 5-Year Age Cohorts, US Census Bureau

Prime home buying years (the age 30-39 cohort) is not due to peak until several years from now.

Figure 4: Age Projections

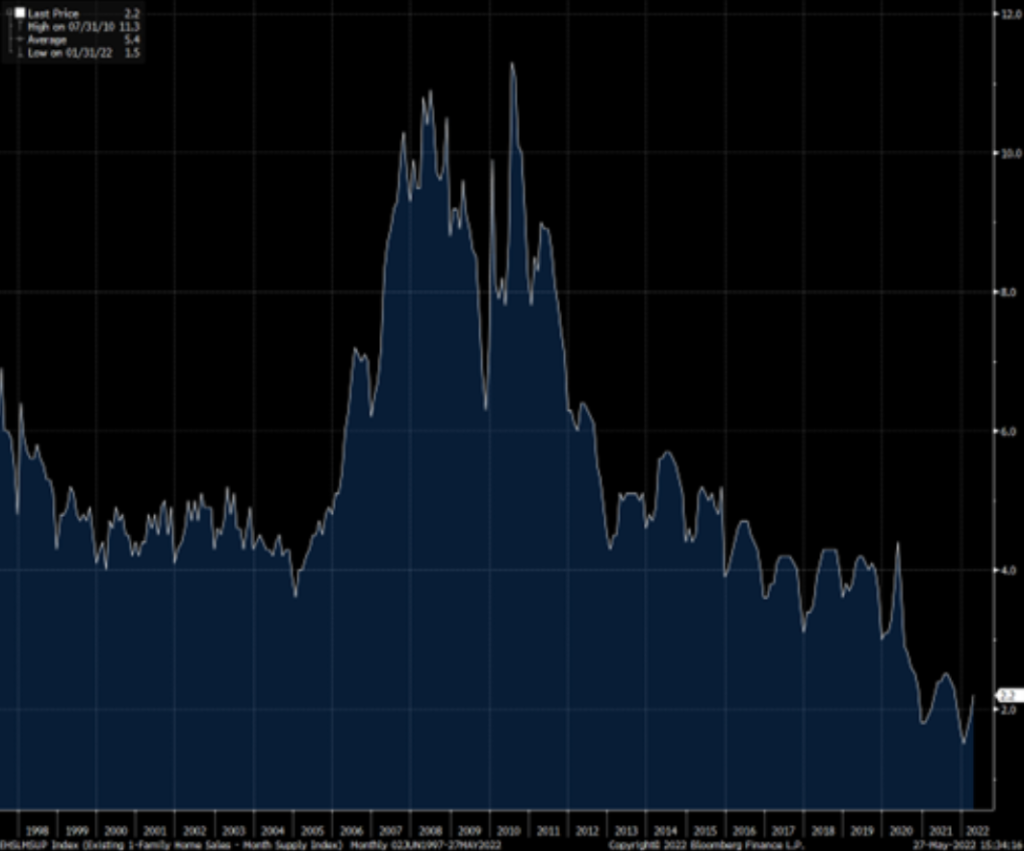

Covid-induced demand certainly pulled forward purchases. One new paper from economists at the San Francisco Fed believe remote work accounts for at least 50% of the increase in home prices we’ve seen since 2020. But as long as household formation continues then the current decline in activity should be seen as a pause and digestion rather than a reversal. After all, the US economy is still laughably short housing stock.

Figure 5: US Months Supply of Housing Inventory Just Off All Time Lows, National Association of Realtors

4. Hopes for a Soft Landing

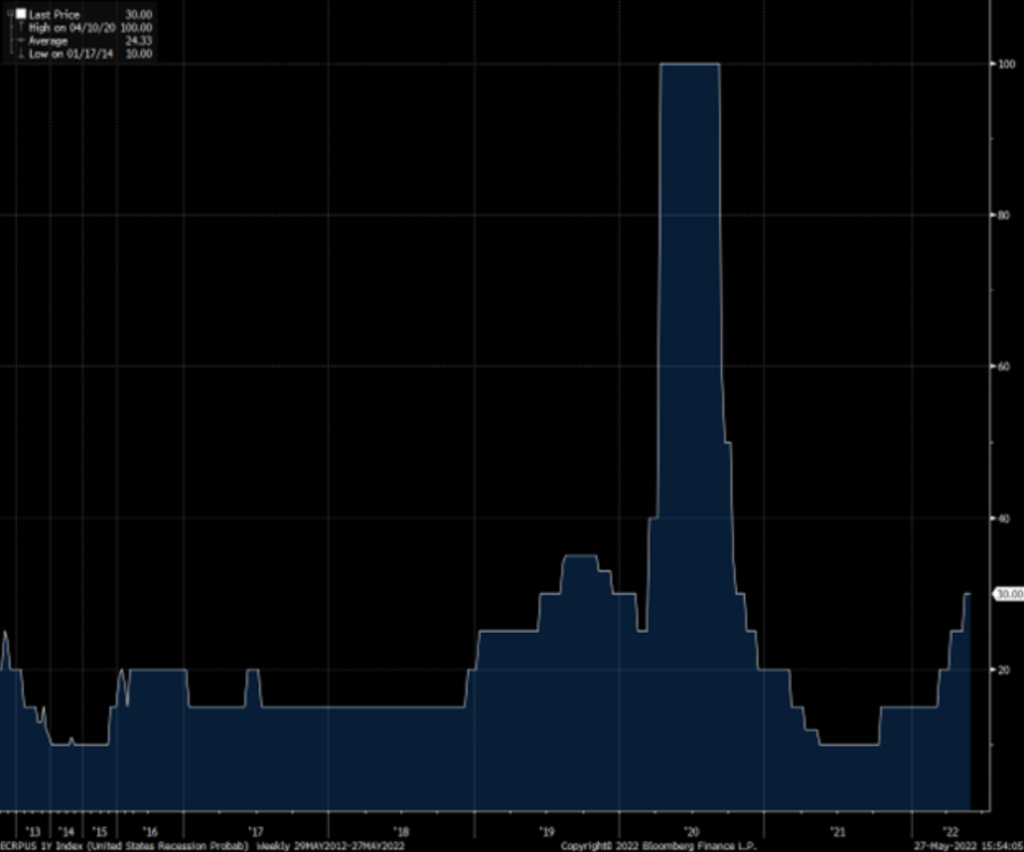

Forecasts and the risks of a recession are elevated according to a wide array of sources. Bloomberg’s compilation of recession forecasts concludes current probabilities of a recession at 30%, one of the higher levels in the post-GFC era.

Figure 6: Forecasted Probability of a Recession at 30%

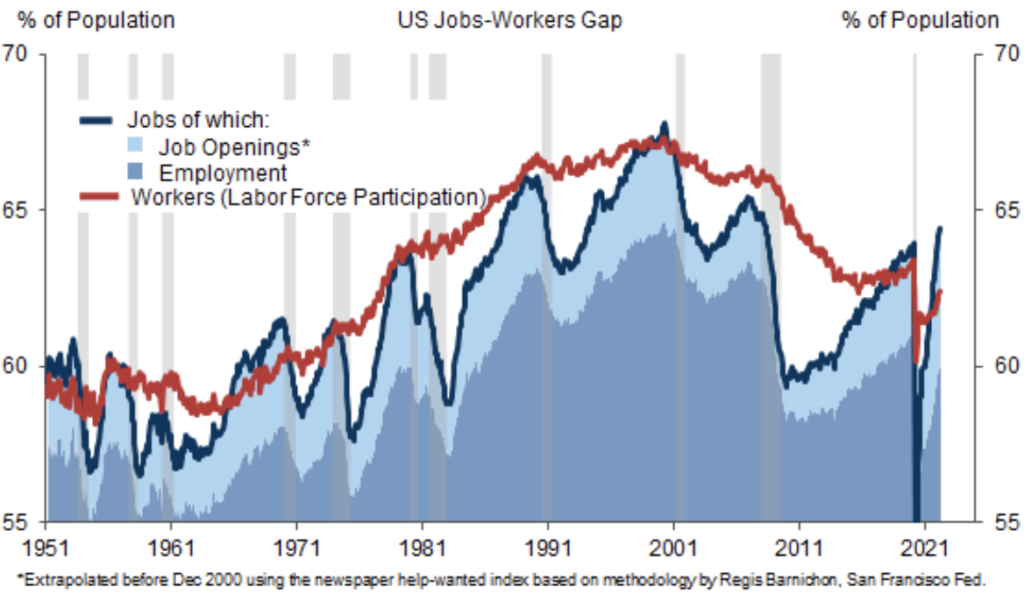

Corporate commentary could not be more opposite to this level of sentiment, blaming weakness instead on weak international demand (largely due to the terrible results of zero-COVID in China), bungled supply chains, and inflation. One thing supply chains cannot fix is a shortage of workers; according to Goldman Sachs the current gap between jobs and workers is the largest since World War II.

Figure 7: Largest Jobs-Workers Gap Since World War II, Goldman Sachs

Their economists go on to estimate that the gap currently stands at just over five million workers. Such a gap explains the acceleration in Average Hourly Earnings, the Employment Cost Index, Unit Labor Costs, and any other measure of wage pressure in the current economy. Of course, these wage pressures feed directly into inflation and the needed tightening cycle the US and other developed economies find themselves in.

Goldman goes on to estimate that shrinking this jobs-workers gap by half to 2.5 million would be enough to slow wages down so that overall pricing pressures in the economy conform to the path targeted by the FOMC.

The problem, as Goldman itself admits, is that shrinking a gap of that magnitude has never happened in history without a recession.

Whether or not a recession is at our doorstep is beyond the scope of this piece, but prognosticators do have a tendency to overprescribe them. The larger issues with Goldman’s analysis stem from an optimism regarding inflation coming from sources such as food and energy. There has been a chronic underinvestment for several years due to capital destruction in some of those spaces and it could put policy makers in between a rock and a hard place.

The one small piece of good news is that balance sheets are in a far better place in this economic cycle than they have been in quite a long time. Households and Businesses both have far more cushion to deal with an economic downturn. It won’t prevent a recession, but it may help prevent the worst traits of a recession take root.

Figure 8: Households and Businesses Are Not Imbalanced Like Cycles Past, Goldman Sachs