The Wooden Nickel is a collection of roughly a handful of recent topics that have caught our attention. Here you’ll find current, open-ended thoughts. We wish to use this piece as a way to think out loud in public rather than formal proclamations or projections.

1. Dutch Disease – Micro Edition

In 1959, underneath the city of Groningen in the Netherlands, geologists discovered 2.8T cubic meters of natural gas. The discovery marked the largest field of natural gas in Europe. But what was supposed to be a blessing turned out to be a curse. 18 years later, The Economist coined the phrase “Dutch Disease” to mark the quandary of why this supposed gift of wealth undermined the country’s competitiveness. Rather than riches, the Netherlands saw rising unemployment, deindustrialization, currency volatility, and a lack of capital for other parts of the economy. While there have been some clarifications and additional study surrounding the inaugural case, it wouldn’t take anyone very long to think of additional instances in which commodity-endowed economies suffer from similar symptoms (and some far worse, such as public corruption).

I’ve come to believe that some Portfolio Managers are afflicted with a type of Dutch Disease when building portfolios. Similarly, it reflects underdeveloped thinking. Thought processes and the theses they develop are, by-in-large commodified; unfortunately, they fail to realize it. How to get involved with AI? Buy power companies! Electric Vehicles set to take share? Buy silver and copper! Data is the new oil? Buy manufacturers of silicone wafers; you literally cannot have semiconductors without them! It’s an oligopoly after all. Here’s how that would have worked out for you the last few years (white) against some high-flyers, but also against the general Semiconductor index (green). When even Intel outperforms such a thesis…

Figure 1: Lowest Common Denominator Investing is Dangerous

This exemplifies the difference and danger in failing to distinguish between a simple thesis and a simplistic one. Whether out of ignorance, sloppiness, or some other factor, a simplistic thesis usually emanates from a failure to appreciate nuance, namely that there exists a hierarchy of value. In some economic transactions, some parties win more than others. While all people are created equal, businesses are not, and investors should recognize that fact.

2. Base Rates and Quality

“People who have information about an individual case rarely feel the need to know the statistics of the class to which the case belongs.” — Daniel Kahneman

People often fail to see proper analogies between present conditions and past circumstances. It doesn’t happen just in investing but in other professions and contexts as well. It’s why “this time is different” has pejorative connotations; we often place far more weight on our own problems rather than stepping back and looking to see what happened to others in similar circumstances in the past. History may not repeat, but it does rhyme. The same can be said of our current investing paradigm, despite innovations in things like Artificial Intelligence and GLP-1s. The Nifty-Fifty Era and Dot-Com era share plenty of similarities.

While the default case of projecting future financials involves extrapolating from the recent past based on bottoms-up, technical knowledge, investors would be better off if they also incorporated historical case studies to find out what has happened to companies in the past during similar circumstances. How long does success run? What is the probability that EPS can grow 10% per year for 10 years? If you’re signing up to participate in the market, why not know all the probabilities ahead of time before rolling the dice?

Morgan Stanley’s Michael Maubossin has long touted the wisdom in examining current cases as another sample in a historic set, and his work quantifies these very probabilities. If nothing else, they ground the investor into asking “what has to be true” to avoid being run over by the probabilities.

Let’s take a basic example. Costco is a beloved company by consumers and investors alike. 25 years ago, it had a $17B market cap and had less than 300 stores. Today, the market value of Costco’s shares approach $400B on a store count that has tripled. In the meantime, its story and value proposition are well known. Its simple (but not simplistic) business model exemplifies many virtues commonly sought after, from delighting shoppers to prudent capital allocation, humble management, and a durable competitive advantage. While the model is simple, it delivers, historically, to the tune of 11% Earnings per Share growth in the last 25 years. But today it trades at over 54x earnings for the next 12 months. Just how much success is priced in?

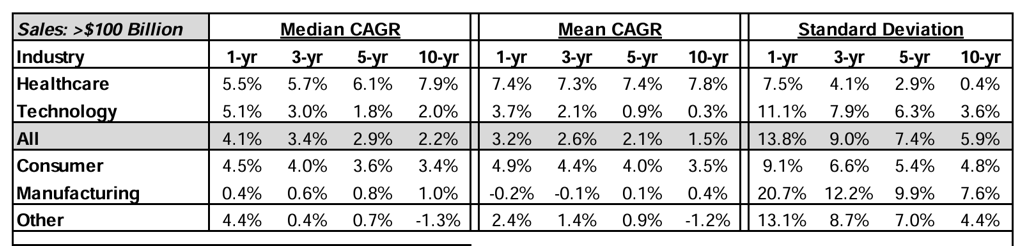

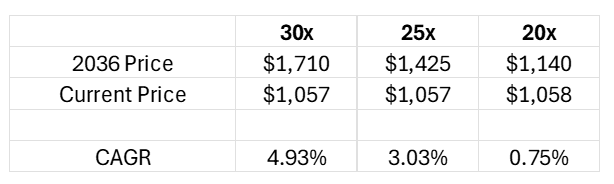

Figure 2: Base Rates, Source: Michael Maubossin

As demonstrated in Figure 2, just maintaining the historical rate of growth is anything but easy. Less than 1% of all observations historically (337 out of 37,305 cases) grow faster than 10% for more than 10 years, but for the sake of the exercise let’s assume that it is part of the ½ of 1% and that it continues to deliver the 11% EPS growth for the next 10 years. And then let’s be generous and give it a multiple on its earnings from that point on of 30x. Not for one year…but for perpetuity. The result? You’re probably better off in the bond market.

Even the best of businesses get priced for perfection sometimes.

3. Recommended Reads and Listens