The Wooden Nickel is a collection of roughly a handful of recent topics that have caught our attention. Here you’ll find current, open-ended thoughts. We wish to use this piece as a way to think out loud in public or bring attention to facts and findings that we find interesting rather than always making formal proclamations or projections.

1. Overlooking Oil Demand

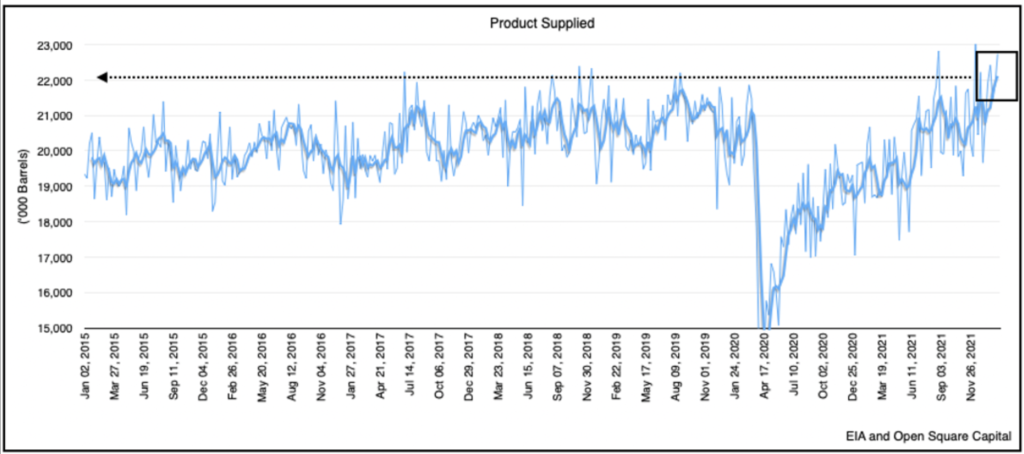

Despite being the middle of winter, a seasonally weak period, oil demand in the U.S. has reached levels we’ve never seen before and is now roughly 1 million barrels per day higher than 2019. That’s despite multiple drivers of reopening activity nowhere close to 2019 levels, namely air travel. TSA check-in data is still 10% below 2019 levels and the rest of the world is much further behind the U.S. in opening up and resuming pre-pandemic activities.

Figure 1: Oil Demand at Record Highs, Open Square Capital

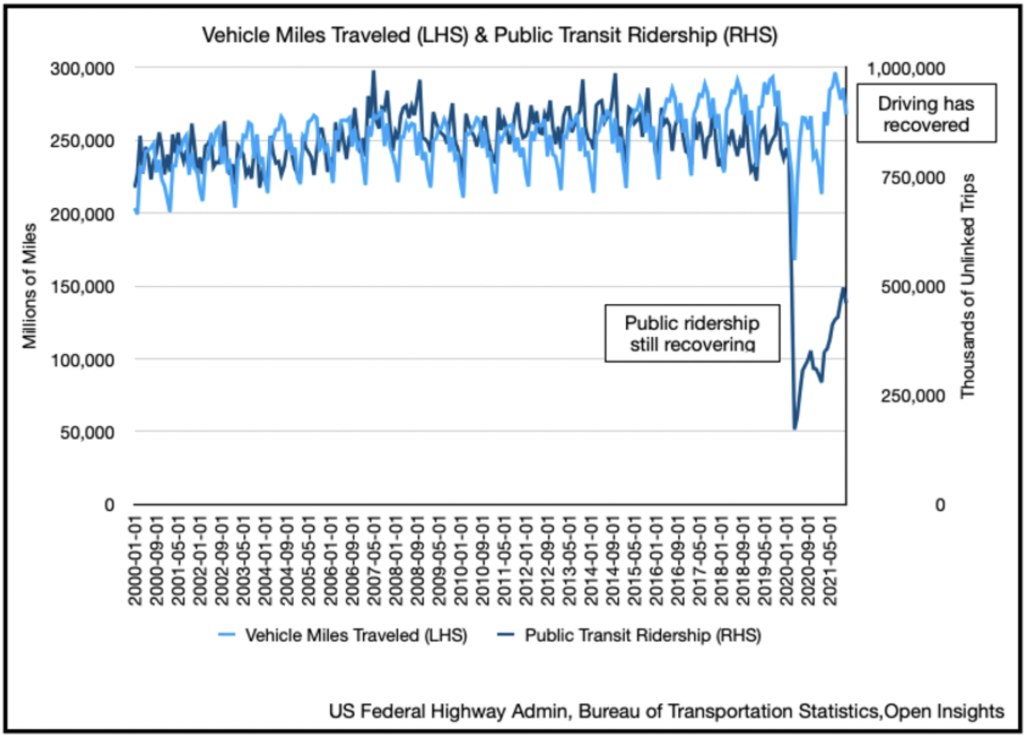

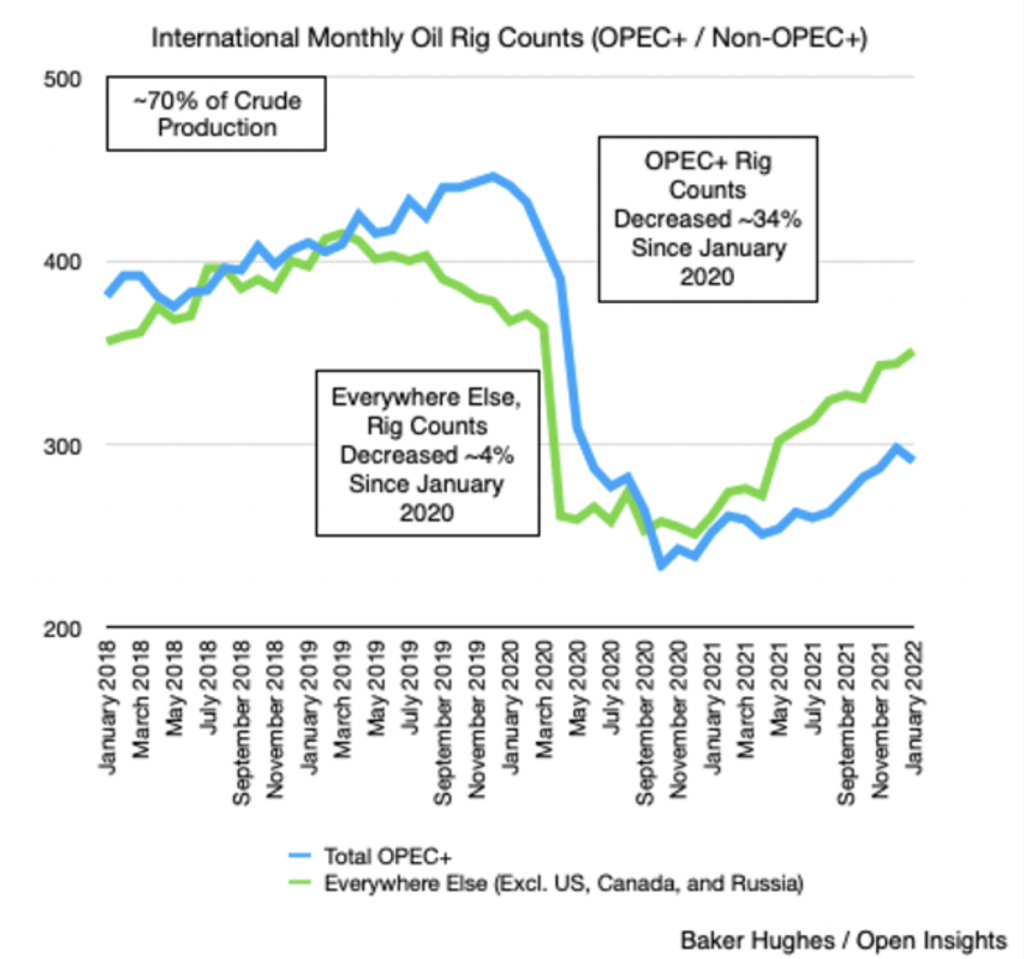

A renewed interest in driving over public transport, the resumption of air travel, and a more engaged manufacturing base globally to meet the surge in demand seen the last two years, all spell higher oil demand/prices ahead. And relief is not coming from the shale patch and is invisible from the OPEC rig count.

Figure 2: Supply Relief is Far Away, Open Square Capital

A fuller explanation of the demand/supply imbalance in the oil complex can be found here. The larger point is that there is a current under-appreciation for just how much demand is the primary culprit for pricing pressure (rather than supply chains or geopolitics), and just how far we still have to go before all potential catalysts play out and get priced in.

2. There Will Always Be Centralization

Conversations about Bitcoin specifically, or crypto securities in general, tend to take on a religious or cultish fervor between the ardent maximalists who believe putting everything on a blockchain solves any problem imaginable, and the cynic who views them as nothing more than regulatory arbitrage to facilitate illegal activity. As usual, the truth lies somewhere in the middle.

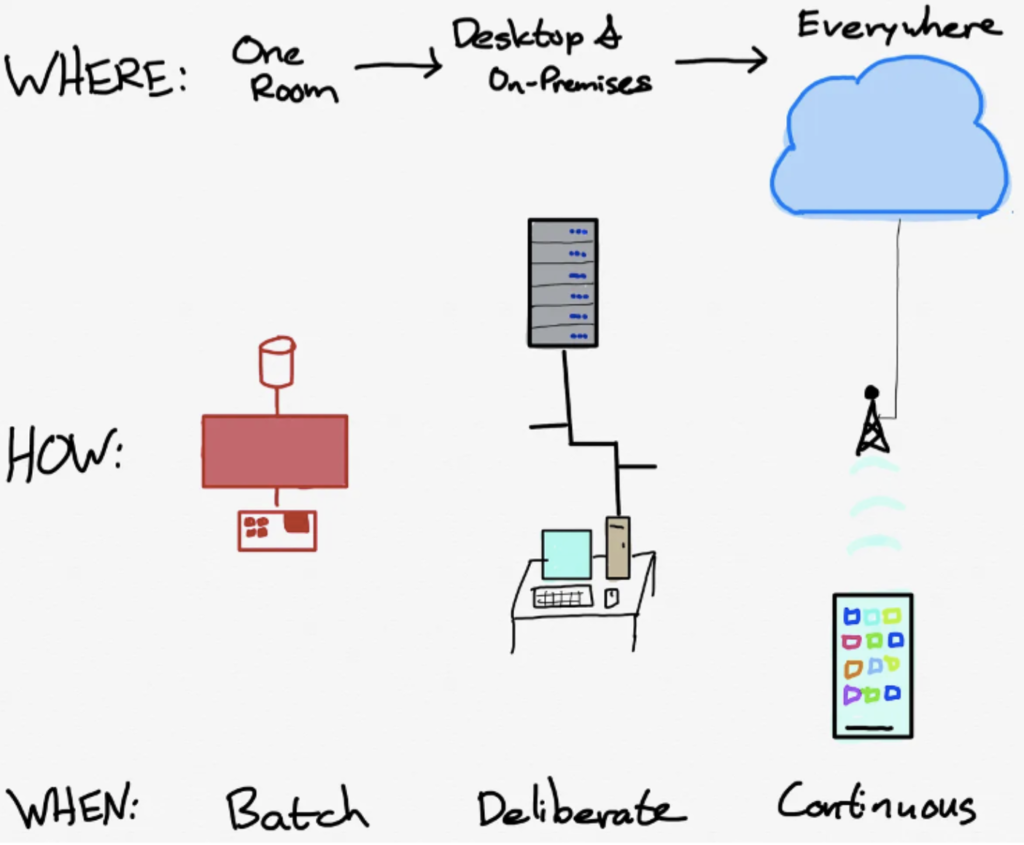

Most discussions between factions largely miss the forest for the trees. In reality, centralization and decentralization are two sides of a coin. Technology history has shown us that extending the benefits of a new innovation to the masses requires a centralized entity standing in between offering some level of abstraction and simplifying complexity for end-users. Good luck trying to use any part of the cloud without some level of centralization. But it’s precisely that centralization of hardware, software, and services that has allowed for the greatest distribution of computing power that we’ve ever seen. It’s far easier to have a select few, competent providers building out the cloud rather than each and every person who wishes to participate set up their own server, middleware, database, and applications and hope that it can all work together. It’s what allows for an accountant to start their own practice, a merchant to accept payments and track inventory, or a farmer to find the best price for their crops. Centralization, at some point in a value chain, leverages an abstraction of complexity so that new markets and use cases can be made available to the masses

The world is littered with examples of the above. The advancements in artificial intelligence for modeling weather, speech, fraud detection, etc. wouldn’t be possible without Nvidia’s work to create a centralized pivot point whereby developers and engineers can program chips for accelerated computing. Visa was created so that back-office functions could be automated and free up working capital; instead of manually checking and authorizing payments the software did it for you. Microsoft’s operating system abstracted away the complexity of writing lower level machine code so that engineers could dedicate their time and resources to building front-facing user applications. The point is that regardless of whether a specific piece of infrastructure is built on a centralized or decentralized network misses the point; the long march of computing history is a spectrum pointing to a more and more continuous computing experience. Whether centralization or decentralization is better is only relevant towards that end goal. Computing has moved from a back room to our desks to our pockets in the last 70 years. But where it happens is irrelevant. The point was always for it to be closer and closer to the end-user.

Figure 3: Computing Has Become More Continuous With Each Manifestation, Ben Thompson

Blockchain services are emerging for similar reasons as their counterparts in previous generations of the internet. The core technology at the heart of the blockchain is slow, clunky, difficult to work with, doesn’t scale well and is erratic in terms of cost structure. It’s no surprise then that, if there is value to be built with it, some entities come along serving as a centralized gateway (Coinbase, FTX, Open Sea, etc.) to the blockchain to provide better functionality, scale, and user experience.

Whether or not it’s better to own these front-facing services or the underlying tokens themselves (assuming either one is worth it) is too soon to be known. The major blockchain networks may resemble the major computing platforms in the market today (AWS, Azure, Google Cloud) and collect royalties as more and more infrastructure gets built on top of them, increasing the underlying token’s value. The funny thing about this analogy though is that every cloud computing platform (along with dozens of other crucial infrastructure software) all sits on top of the Linux open-source operating system. The world as we know it would literally not exist without this open standard, decentralized piece of software. Yet, value for investors and for society as a whole didn’t exist until the core technology got coopted by major players. To use an analogy from energy, an investor would have been far better off owning the companies who used the new technology/innovation as an input (a la Exxon Mobile) versus the raw commodity itself (oil). In much the same way, the blockchain may evolve such that the core blockchain tokens like Bitcoin and Ethereum are the crumbs and the real meal comes along with those who co-opt the technology to make it addressable for the masses.

3. The King Stays the King

A historic Financial Crisis. Rising deficits and debt load. Quantitative easing. Demographic challenges. Slow economic growth. New geopolitical challengers. Despite every single one of those supposed death sentences, the US Dollar’s proportion of global assets and influence has only grown in the post-GFC world. And its rise has not been meager either.

Figure 4: The Dollar’s Proportion of Global Corporate Rate Has Increased 50%, Verdad

In a recent post, Verdad Capital shows how the global economy’s dependence on the greenback has only grown in the decade after the Financial Crisis. Despite every possible reason imaginable, the world’s enormous dependence on the dollar is not going anywhere anytime soon. Inertia is a real and powerful force.

As we learned in The Wire, “The King stay the King.”

4. Margin Squeezes

One of the common, and compelling, bearish cases for equity markets is that despite projections for solid economic growth and healthy household balance sheets, large-cap stocks could see operating deleverage, leading to EPS growth that is lower than top-line growth.

Companies in the S&P 500 have expanded their margins for six consecutive quarters. But input costs tend to hit corporate income statements on a lag. Considering that inflation didn’t start to accelerate until the second half of 2021, it’s not hard to envision this streak of margin expansion ending. And that’s before anyone considers the increase in logistics costs or energy costs we’ve seen in the first two months of 2022.

Figure 5: S&P 500 Gross Margins Have Expanded for Six Straight Quarters, Empirical Research

Further, there are plenty of common expenses that corporations have not brought back yet that will only crimp margins further. Much of corporate travel hasn’t returned. Expenses to run an office are far from their pre-pandemic levels as well. Finally, the economy is estimated to still be roughly 3 million jobs short of 2019 levels. Those jobs are being added at higher and higher compensation levels too. Thus, you have a scenario for both gross margins as well as operating margins to both be hit from different forces hitting the income statement in different ways. It wouldn’t be surprising in the least to see a top-line expansion in line with nominal GDP but EPS to be barely positive at all.