The Wooden Nickel

The Wooden Nickel

-

Author : The BlackSummit Team

Date : May 7, 2024

The Wooden Nickel is a collection of roughly a handful of recent topics that have caught our attention. Here you’ll find current, open-ended thoughts. We wish to use this piece as a way to think out loud in public rather than formal proclamations or projections.

1. Changing Lanes

There’s a great episode of the show House M.D. where 4 prospective employees are competing for 3 spots on the most prestigious clinical diagnostic team in the country led by an acerbic medical and scientific genius. Throughout the trial run whereby the 4 candidates are trying to earn the respect and impress the mind of Dr. House, one candidate exceedingly stands out. He finishes Dr. House’s sentences, effortlessly refutes competing theories with an encyclopedic knowledge of infectious diseases, and generally sees connections and relationships among symptoms and details that the other three do not, prompting Dr. House to most frequently pursue his theories over the other 3.

When the time comes for the final cut to get down to the requisite 3-member team, “shocked” does not begin to describe the reaction of the viewer and the applicants when Dr. House decides to cut the very applicant with whom he agreed the most and thought the most like. When one of the (winning) applicants in a perplexed manner asks Dr. House why he made his decision, the very candidate who was cut interrupts and says “Because you don’t need someone telling you something you already know.” To put it in investment terms, his theories, synthesis of facts, and knowledge were “priced in.”

For anyone who’s been stuck in a traffic jam on a multi-lane highway, then I’m sure you’ve watched as one lane of cars smoothly progresses while you stare at the license plate of the car in front of you. Your jealousy grows second by second, and after 15 seconds goes by, your jealousy boils over and you start to maneuver your car over into the lane. You move maybe a handful of spots up before you are back in bumper-to-bumper traffic. To add insult to injury, the lane you had just departed starts progressing forward faster than the one that everyone else flocked to with you in your growing impatience.

For the last 18 months, the dominant narrative in the US economy and what has actually been happening resemble the lane hopping scenario I highlighted. Consider the following:

- In the fall of 2022, the dominant narrative was that a recession was on the way. Confirmation bias was easy to attain in the face of the fastest hiking cycle this generation had ever seen and was even further affirmed by a stock market that had lost 40% of its value and excesses in bubbly areas like crypto and SPACs popped. 100% of economists polled by Bloomberg forecast the onset of a recession within the next 12 months. But what actually happened was an economy that slowed from excessively high rates as (some) high-velocity stimulus wore off, but one that still managed to grow slightly above 2% on a real basis. The continued macro expansion caught everyone offside.

Figure 1: Everyone Priced in a Recession

- By the time people started to come to grips with the steady expansion, the economy again moved away from their narratives. As we highlighted, instead of muddling right along, the economy accelerated led by the consumer, government investment, and trade. Inflation came down and yet real GDP growth accelerated to over 5% in the latter part of 2023. Again, people were in denial that the economic expansion was real, let alone accelerating.

- By the time people were digesting the reality of the economic acceleration, again the macro narrative was shifting beneath their feet. The acceleration part had become “priced in” by the time they had hopped aboard that narrative train. What was next was higher rates for longer and an end to the downward path of CPI that the latter half of 2023 saw. Indeed, in January, Fed Fund futures were penciling in between 6 and 7 rate cuts with the soft landing being crystallized in 2024.

- From where we sit today, the hopes for that sort of glide path down on interest rates can be kissed goodbye. The data has not allowed the Fed to embark on the cutting cycle they’ve hoped for, although they do clearly still hold out hope that it may be sparked later this year. In fact, looking out to 2027, futures markets are only pricing in a total of 3 cuts between now and then. In essence, people are betting that the economy we have today is the economy we will have for the next 30 months. Considering the multiple environments we’ve seen over the last 18 months, I’m not sure where some people get this kind of confidence or if the futures market is one giant shrug of the shoulders saying, “I don’t know.”

Throughout these past 18 months, settling on the dominant macro narrative has been the greatest of opportunity costs. You do not get paid for something that everyone else already believes and has paid up for. If you were positioned for a recession in late 2022, you saw the market race ahead of you. If you were positioned for steady economic growth in 2023, you saw the market race ahead of you. If you positioned yourself for economic acceleration in 2024, then you might be wondering why cyclical areas like Small Caps are down for the year and defensive areas of the market like Consumer Staples are up 5% year-to-date versus the more economically sensible Discretionary sector which is up only 1%.

This is the folly of basing your portfolio construction on macro or other top-down investment styles which are simplistic and easily imitated. Unless you’re one of the first to change lanes, you’re unlikely to make much progress before being stuck again; they get priced in very quickly.

2. Capital Intensity and Quality

Andrew Rangely has a good and thought-provoking piece on his website about a massive bid in stocks that have durable economic models, generate strong returns on their invested capital, and have probably been bid up to the point where any long-term return potential looks exceedingly low and speculative. Names like Costco and Wingstop have seen their equity pushed up to prices and multiples that border the obscene. As much as I personally love Costco as a consumer and admire it as an investor, I don’t think anyone buying at these levels will make money for 10 years.

I think there’s a general misunderstanding and underappreciation for stocks that are absolutely quality companies with durable business models, wide moats, and generate a strong amount of free cash flow while simultaneously being capital intensive. Capital-light versions of business models in areas like restaurants or hotels tend to attract far more attention and admiration from investors than their more capital-heavy peers, even though they operate in the same industry. And while model transitions have helped buoy returns to investors, I wonder if there’s been an unhealthy calcification in thinking that only capital-light companies can be thought of as quality. It has sparked a classic logical propositional fallacy that just because something is capital light, it must mean that it is quality, and I think that makes the bar too low.

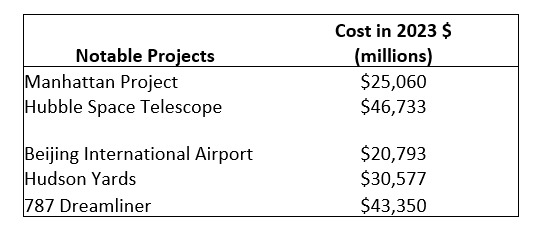

Just look at some of the largest tech companies today. It would be quite hard to argue that they do not meet the criteria to be considered quality, yet people have glossed over just how capital-intensive they have become. Microsoft alone will be spending north of $40B in CapEx this year and that number is only going up. For some perspective, some of the biggest projects in world history fall short of what Microsoft will spend this year. Then consider that Google, Meta, and others are also piling in with their own visions.

Figure 2: A.I. Cap Ex is of Historic Proportions

Or look more narrowly within software. It would be easy to look across the spectrum of software names and conclude that based on the selected list in Figure 3, CoStar’s business is of inferior quality and competitive strength. But that’s very much a superficial read of things. Its core business is extremely labor intensive but that’s actually the moat. Whereas there is very little friction in building a software business on top of Amazon’s or Microsoft’s infrastructure, there is an enormous amount of legwork in building up a real estate software business that pulls pricing data, lease data, occupancy information, loan details, and much more in a manual manner that wards off competitors. If a unique process that deters competitors and imitators doesn’t meet the threshold for quality, then I’m not sure what does.

Figure 3: Spot the “Low Quality” Name

3. Rates and Inflation

In the peaks and valleys of any market, you’ll start to hear murmurs from “experts” who attempt to explain some pretty ridiculous things. The latest is that the interest rate increases of the past two years are now causing a resurgence in inflation rather than stemming it. The belief is that the elevated level of rates is supporting the economy via elevated interest income and supporting spending levels; people with excess cash now have some real spending power with rates at 5%.

I’m sure there are isolated cases where this is true. Households that own assets and were wise enough to term out debt at lower rates may be seeing an extra boost to their monthly income thanks to payouts from money market funds. But it doesn’t take much math to come to realize that this is A) probably a very small segment of the population, B) the level of assets earning this kind of monthly income has to be pretty high to support monthly consumption in a material manner, and C) the disproportionate income benefit will undoubtedly accrue to the wealthiest households whose money market returns are not a material driver of marginal consumption.

Dario Perkins makes this point more eloquently and thoroughly at TS Lombard’s blog. While pure income effects may seem positive on the surface, it’s an immensely shortsighted view when breaking down the composition of which households are net debtors and which ones are not, and their respective consumption patterns.

4. TIPS Pricing

I find that investors continue to underappreciate the role of TIPS in a portfolio, and my most frequent takeaway is that they don’t take the time to understand how returns are generated. The good news is that it doesn’t take much time to learn; they are simple securities to understand and appreciate.

To start, the principal value of the bond is adjusted based upon an inflation adjustment factor that the Department of Treasury publishes each day. Inflation adjustments are based upon the Consumer Price Index, but the non-seasonally adjusted version of the index. The coupon rate of the bond is fixed but is based upon the updated principal value of the bond. The difference between the yield offered by a TIP and its nominal counterpart is considered the breakeven rate, or the implied inflation rate embedded in the bond’s pricing level.

If inflation is 3% on a TIP that is auctioned with a breakeven assumption of 2% inflation, we will see its principal revised up from $1,000 to $1,030 ($1,000 * 3%), and the coupon payment goes from $20 to $20.60. The investor benefits from the appreciation of the principal (if held to maturity) and higher coupon payments to protect from inflation.

But where I find most investors don’t understand TIPS well enough is that there is a lag to the inflation adjustments of approximately two months. To use an example, an investor last month eyeing the 1-year TIPS maturing in April 2025, would receive the inflation adjustments for February and March. The breakeven rate on this security had an embedded inflation assumption of approximately 2.65%. But with the February and March CPI reports coming in hot, they’d already have 1.2% of that embedded return in just two months. This means that in order for the April 2025 TIPS to be priced appropriately, the CPI for the remaining 10 months until maturity would have to come in at roughly no more than 1.45%; that’s a 2% annualized rate when we haven’t seen that at all so far in 2024. If CPI doesn’t fall quickly or precipitously later, the investor is left with an excess return, or what we call alpha.

Figure 4: TIPS Pricing Example