The inverse correlation between the US dollar and emerging markets currencies is a well-known fact. That inverse correlation has been affirmed again over the last few months as the greenback gains ground against emerging markets currencies, in lieu of higher interest rates in the US.

The graph below shows that since late January of this year the dollar has been making significant gains against emerging markets currencies.

Source: Financial Times

Of course, the greenback’s gains are not just only against emerging markets currencies but also against the Euro (among others). We would not be surprised if those gains continue for the short term given three main developments that are happening: First, higher interest rates in the US, naturally strengthen the greenback. Second, growth deceleration outside the US in association with higher US rates reverses the flow of funds in favor of the US. Third, geopolitical uncertainty strengthens the greenback as it is seen as a safe haven (we still believe that the #1 concern is a war in the Middle East involving Iran).

Our focus in this commentary is to draw some basic conclusions about Turkey, Italy, Venezuela, and Argentina (TIVA), given the turmoil in those countries. Let’s start with Turkey.

Turkey was a darling for hedge fund managers 15 years ago. It was reforming, making significant progress, opening up, and had very good prospects. Unfortunately, a major reversal has taken place and the autocratic government has been undermining not just the economy but also whatever democratic institutions had existed. The lira has been shrinking in the last 12 months and who knows where the bottom may be, as shown below.

Turkey’s current account deficit is one of the largest in the world, which simply tells us that there is too much reliance on foreign capital. We do not expect foreign capital to show up because there is capital destruction, and when that happens capital flies out. The heavy Turkish borrowing in foreign currency could signify repayment problems down the road, let alone a recession. Inflation is a major problem, and all these are ingredients of a crisis. There is no Kemal Dervis around (as in the early 2000s) to implement sound policies. On the contrary, the central bank is being bullied around in favor of economic populism (and we all know the mess that created in Argentina during the days of the Kirchners). If a crisis erupts, will Turkey be able to absorb it (especially if global savings are in retreat) or will it create a geopolitical event in the Aegean?

Bottom line: Shortening Turkey might pay off.

Let’s now review the latest developments regarding Italy. Until Sunday evening, the then-emerging populist government with an anti-EU spirit had been creating jitters regarding Italy’s future and consequently EU’s future. (On Sunday evening the news broke that the President of the Republic had rejected the proposed minister of finance – who was disliked by Brussels – and hence political turmoil returned to the scene). Italy is the fourth-largest EU economy and a founding member of the EU. However, over the last several years four things have deteriorated Italy’s future:

First, a segmented banking sector (which advances political interests) is suffering from too many non-performing loans (NPLs). Growth requires a healthy banking sector and that does not exist in Italy. Second, the debt level in Italy (close to 130% of GDP) is unstainable given the NPLs and the absence of significant growth. Third, productivity growth has been taking a nap for a long time now. As a result, competitiveness is suffering and market confidence has been declining. Shaky market confidence at a time when the country could be governed by populist coalition could shake up the EU foundations in general, and that of the eurozone in particular. If things deteriorate, a crisis could emerge that will dwarf the 2011-12 crisis. Fourth, the fiscal projection in Italy based on the populist coalition plans could require an extra €100 billion (between minimum guaranteed income, flat tax, and the abolition of a VAT hike). When we also take into account the existing unfunded liabilities, we could say that Italy might be in for a fiscal shock.

Bottom line: A constitutional crisis may be brewing in Italy. If new elections are called, the populist parties may win in a landslide. Limited upside for the euro, more downward is possible.

We turn now our attention to the failed state of Venezuela. Venezuela is endowed with huge oil resources. It has failed – like so many other countries that are endowed with natural resources – to save, invest, and diversify its competitive advantages, and has ended up ruled by kleptocrats who robbed the people of their future. Its people lack the necessities of life, inflation runs at 14,000%, debt has skyrocketed, the GDP has been reduced by at least 40% since 2013, the poverty rate exceeds 75%, and the country is collapsing. The squandering of its resources has transformed a beautiful country and abundance of capital into what the Wall Street Journal reported last weekend as “zombie movie sets”.

There is no need to show graphs about the failures produced by tyrannical regimes.

When institutional checks and balances collapse, then nations – whether ancient Athens or Rome, or the European democracies of the 20th century – are susceptible to tyrants who will rule by fear, destroying wealth, opportunities, and the country’s potential.

Bottom Line: When politics loses its soul, amoral failed policies will produce failed states.

Let’s close in a more optimistic tone by taking a look at Argentina. In the early part of the 20th century, whether a European immigrant would board a boat to New York City or to Buenos Aires was determined by the flip of a coin. That shows potential and promise. Of course, the picture at the beginning of the 21st century was completely different. In the early 2000s, Argentina defaulted on its $82 billion debt. Markets froze. Poverty and unemployment skyrocketed. The corralito became a reality (frozen bank accounts). The lunacy of boneheaded populism had reached its highest point.

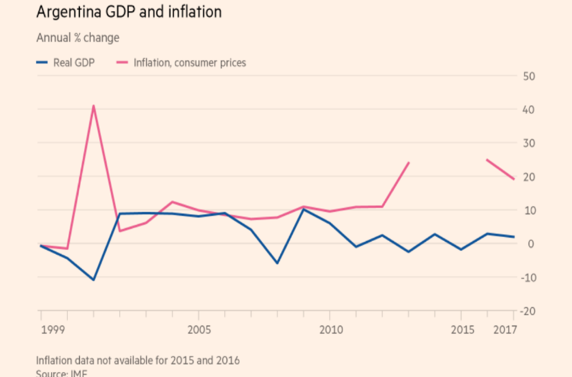

Argentina suffers from unsustainable inflation (inflationary expectations rose from 15% to 21% this year), high debt, high deficits (which feed up the debt), undeveloped capital markets, and unbelievably high interest rates. Given the above, the peso was overvalued at 17 to the greenback (even if it had lost almost 50% of its value since the reformer new president Macri took office in 2015). Over the course of a few days in early May, the peso lost another 20% of its value and negotiations with the IMF are underway for a credit facility.

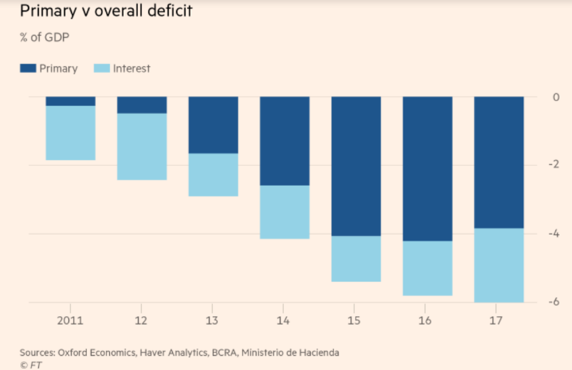

The reforms implemented by Macri, while cautious, carry good prospects and the current turmoil may turn out to be a blessing in disguise, if lawmakers do not undermine the additional reforms needed. The following graphs speak for themselves regarding the Argentinian ills which undermine growth potential (high current account deficit, high primary deficits, and high inflation).

Bottom line: Assuming that reforms continue, and the populists are marginalized, Argentina’s future may be brighter than is currently portrayed.

In conclusion, we could say that these are not ordinary times. We are midway between the tragic and the sentimental, the pathetic and the domestic and like in Handel’s oratorio “Saul” the mental troubles of Handel’s tragic figure are reflected in the policies of some of our “leaders” nowadays.