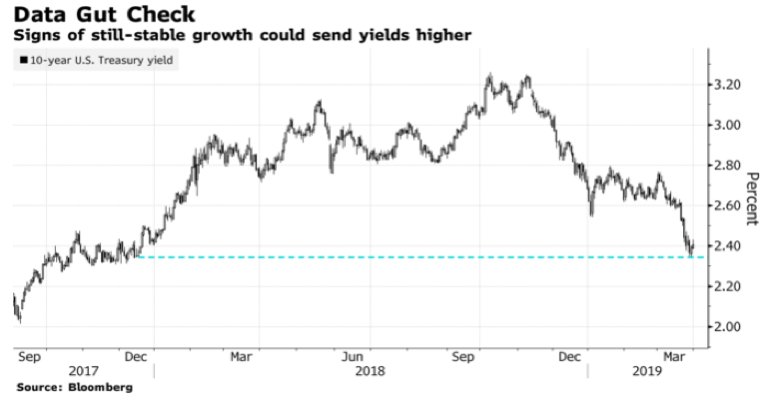

On March 28, the 10-year Treasury’s yield dropped to 2.34% due to exaggerated fears of an imminent recession. The drop in rates in the first quarter of this year (see graph below) and the inversion of the yield curve has created opportunities in both equities and debt/bond markets including Treasuries.

Christine Lagarde, the Managing Director of the IMF, joined the chorus of those who are afraid of “synchronized deceleration” at a time when some encouraging signs were emerging, such as getting closer to a trade deal with China and improved economic statistics in both the US and China.

While the inclusion of Chinese yuan-denominated bonds in the global bond index is a significant event, we would not be surprised if the long-term rates (which are determined by the bond market) reverse their recent drop and start heading north, creating opportunities in inverse bond funds that have experienced significant losses in the first quarter of 2019.

This could happen as – at least for the short term – Chinese slowdown stabilizes at a time of fiscal and monetary stimulus along with capital infusions into that market, and when economic statistics in the US also show signs of stabilization. To this we could add ample liquidity and tight spreads.

If the above scenario starts unfolding, then the emerging narrative of higher rates could break the high correlation among asset classes, which in turn could unnerve investors and their risk appetite at a time of diverging growth patterns even among developed economies. Under that scenario we should also observe higher volatility, which could enhance opportunities for options trading such as selling puts for fairly-valued companies with strong balance sheets and growth prospects.

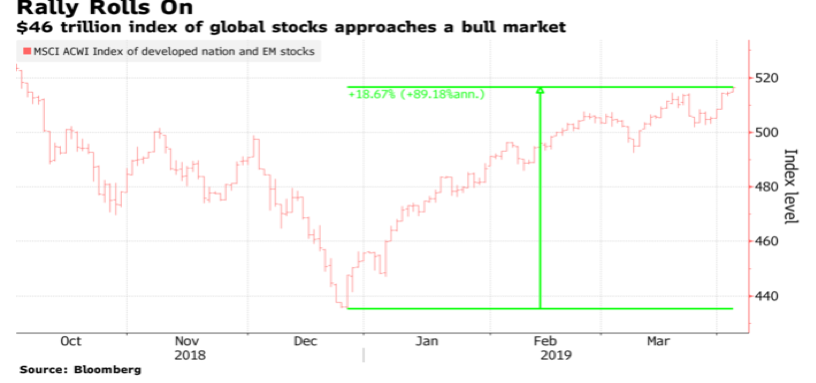

The upbeat tones in economic news (from Chinese recovery, to softer Brexit, and from trade peace to improved sentiment in Europe) have encouraged the risk appetite, as shown below; however, the reversal of rates and the unexpected could again tone down confidence and shake up markets.

The mountain of global debt keeps rising (it stands now at over $240 trillion i.e., more than three times global GDP, excluding the notional liabilities emerging out of derivatives) and has reached pre-crisis levels, while in the US non-financial corporate debt exceeds 72% of GDP. Such trends eventually will restrain capital expenditures and growth and will bring with them downgrades and potential shocks into the debt market.

The mountain of global debt keeps rising (it stands now at over $240 trillion i.e., more than three times global GDP, excluding the notional liabilities emerging out of derivatives) and has reached pre-crisis levels, while in the US non-financial corporate debt exceeds 72% of GDP. Such trends eventually will restrain capital expenditures and growth and will bring with them downgrades and potential shocks into the debt market.

In closing, we should say that the above scenario enhances the proposition that we have expressed from these commentaries recently, calling for a more cautious capital deployment where cash equivalents could play a strategic role.

The Bond Market and Investors’ Assertiveness

Author : John E. Charalambakis

Date : April 4, 2019

On March 28, the 10-year Treasury’s yield dropped to 2.34% due to exaggerated fears of an imminent recession. The drop in rates in the first quarter of this year (see graph below) and the inversion of the yield curve has created opportunities in both equities and debt/bond markets including Treasuries.

Christine Lagarde, the Managing Director of the IMF, joined the chorus of those who are afraid of “synchronized deceleration” at a time when some encouraging signs were emerging, such as getting closer to a trade deal with China and improved economic statistics in both the US and China.

While the inclusion of Chinese yuan-denominated bonds in the global bond index is a significant event, we would not be surprised if the long-term rates (which are determined by the bond market) reverse their recent drop and start heading north, creating opportunities in inverse bond funds that have experienced significant losses in the first quarter of 2019.

This could happen as – at least for the short term – Chinese slowdown stabilizes at a time of fiscal and monetary stimulus along with capital infusions into that market, and when economic statistics in the US also show signs of stabilization. To this we could add ample liquidity and tight spreads.

If the above scenario starts unfolding, then the emerging narrative of higher rates could break the high correlation among asset classes, which in turn could unnerve investors and their risk appetite at a time of diverging growth patterns even among developed economies. Under that scenario we should also observe higher volatility, which could enhance opportunities for options trading such as selling puts for fairly-valued companies with strong balance sheets and growth prospects.

The upbeat tones in economic news (from Chinese recovery, to softer Brexit, and from trade peace to improved sentiment in Europe) have encouraged the risk appetite, as shown below; however, the reversal of rates and the unexpected could again tone down confidence and shake up markets.

In closing, we should say that the above scenario enhances the proposition that we have expressed from these commentaries recently, calling for a more cautious capital deployment where cash equivalents could play a strategic role.