This week, we will be continuing our series on emerging economies with some comments on Africa.

Like many of the regions we have explored in this commentary series on emerging economies, the situation facing Africa presents a two-sided conundrum. On the one hand, Africa is well-positioned to thrive in the economy of the Day After, boasting a young population and abundant natural resources. On the other hand, Africa is home to some of the poorest regions in the world, and a long history of colonialism, exploitation, and corruption reverberates all too powerfully through the area today. In order to achieve its destiny as a fully-fledged member of the global economy, the nations of Africa must walk a fine line between dueling hemispheres, preserving their natural abundance against exploitation while fully engaging in the global supply chain.

Plenty and Poverty

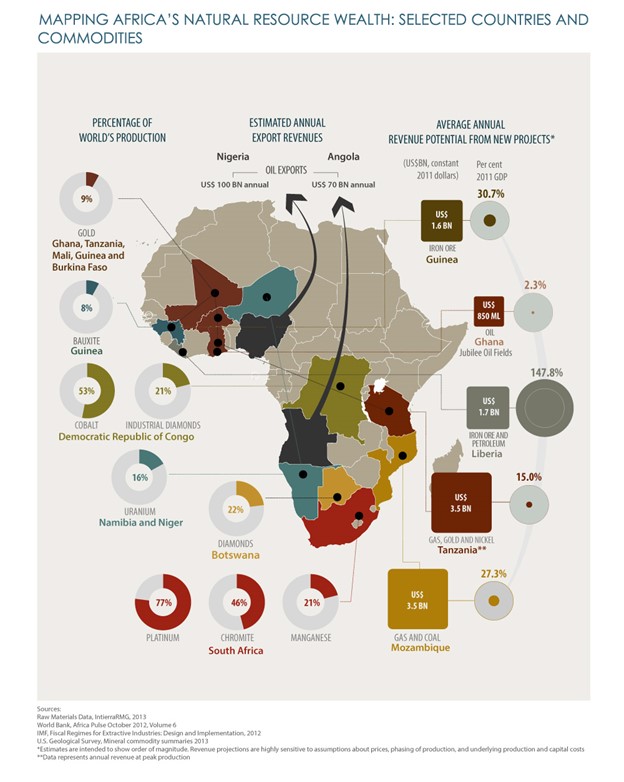

The African continent contains some of the greatest mineral wealth in the world, with the United Nations (UN) reporting that Africa contains about 30% of the world’s overall mineral reserves. In addition, it contains 40% of the world’s gold and 90% of its chromium and platinum, along with the world’s largest deposits of cobalt, diamonds, and uranium.

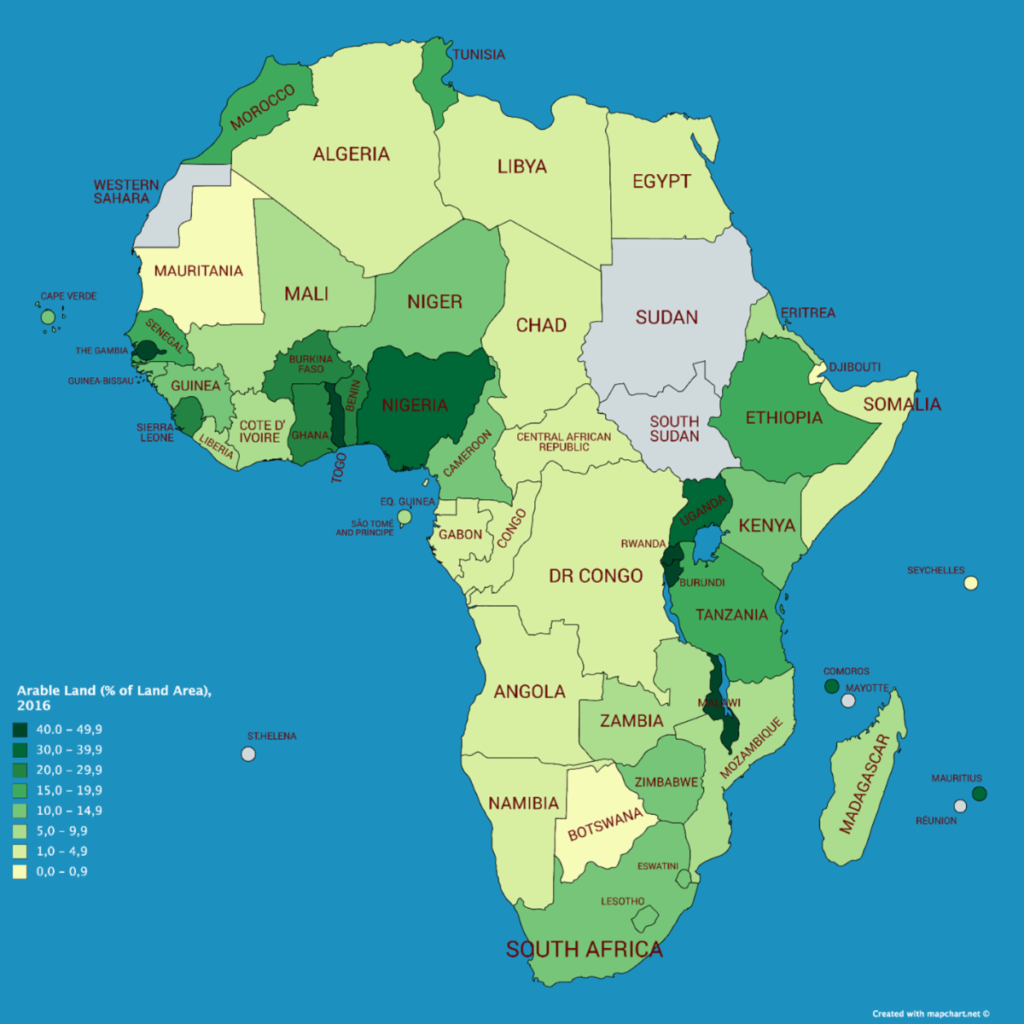

Critically, the continent contains 65% of the world’s arable land, a resource essential to combatting the coming challenge of food scarcity.

Africa’s Arable Land (Source: MapChart)

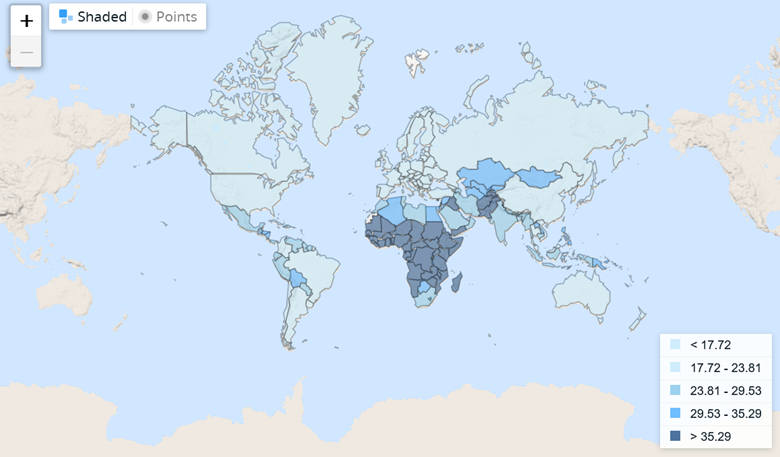

In addition, more than 40% of the population of Sub-Saharan Africa is younger than 14 years old, representing a forthcoming population boom in the working-age category as the rest of the world becomes increasingly aged.

Percentage of Population Less Than 14 yrs. (Source: World Bank)

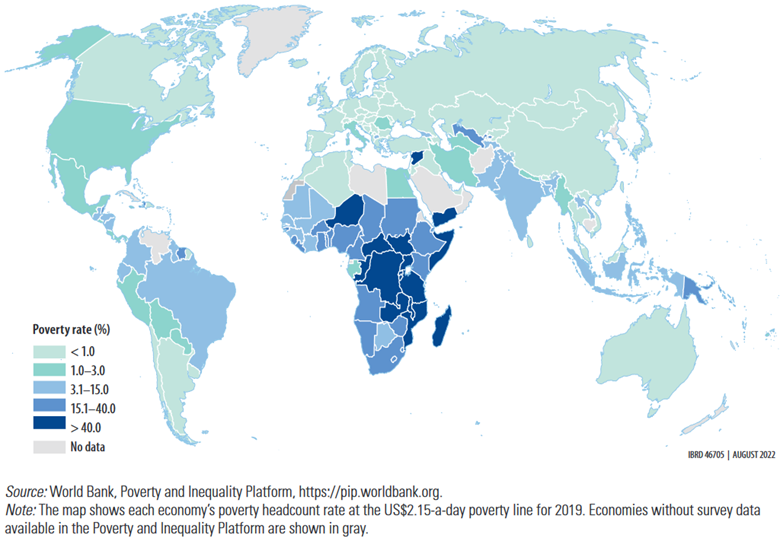

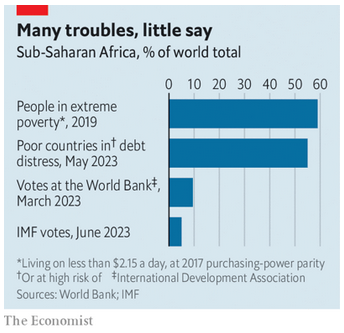

Despite this tremendous wealth of resources, land, and people, it remains the poorest region on Earth, with nearly 60% of the world’s extremely poor population residing on the continent. Many African nations are recipients of large quantities of foreign aid, and their lack of economic power – as well as weak democratic governance – has limited their access to global institutions.

Global Poverty Rates (Source: World Bank)

As a result, Africa has increasingly pivoted away from Western-led institutions and into the arms of the West’s geopolitical foes: China and Russia.

A Battleground for Geopolitical Conflict

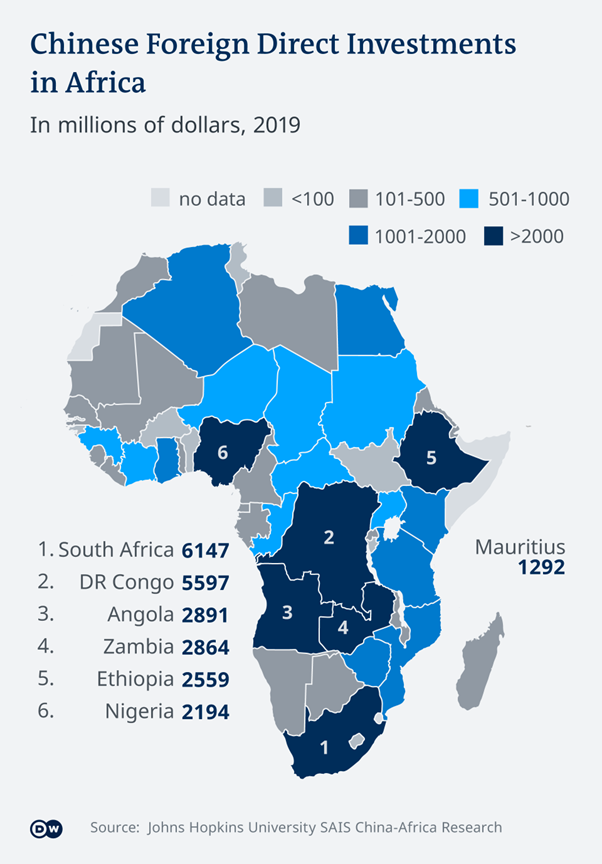

With approximately $43 billion in direct investment, China has significant interest in Africa. Chinese lending constitutes a fifth of all lending to Africa, accounting for $282 billion in commerce with the continent in 2022. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), for instance, China owns about 70% of the mining operations. This investment does not come without cost – Chinese loans are criticized for being opaque, and many blame recent debt crises partially on China’s refusal to cooperate with international lending institutions to restructure debt in the region.

Russia is active largely in the Sahel region, where the country has leveraged the Wagner private military corporation (PMC) to fill in security gaps which were previously filled by the French in countries such as Mali, Central African Republic (CAR), Burkina Faso, and possibly Chad. While Russian gains are not widespread, they could present a problem for the West in relations with these countries. Importantly, as more nations rely on Russian PMCs for security, Russia gains prominence in international institutions and on the world stage.

Russia’s Presence in Africa (Source: Rusi)

On the other hand, the West’s approach largely vacillates between withdrawal and increased interaction, and many believe it has already lost the race. Western firms cannot keep up with the level of money China is willing to send to Africa through private corporations. Even with high-level attempts to win allies in the continent, African nations have repeatedly expressed displeasure with their representation in Western-dominated global institutions.

All of this paints a picture of an African community thoroughly disenchanted by centuries of exploitation by global powers. Despite its potential wealth, the continent is severely hampered by its large population of people in extreme poverty. This, combined with a sense of having been abandoned by global institutions, has driven many African nations to align with China and Russia directly and indirectly. Yet neither of these nations has exhibited a humanitarian or altruistic motivation for aiding Africa – indeed, their involvement mimics the pattern of exploitation established in history. In order to break the cycle, Africa must navigate the incredibly treacherous waters before it, challenging the immensity of the issue posed by poverty without resorting to “easy” money from (and to) corrupt officials. At the same time, total alignment with a West which has at times participated in its exploitation and demonstrated a deaf ear to Africa’s plight presents the risk of again falling into obscurity on the global stage. Rather, the nations of Africa must draw on their combined strength to band together and set their own course, weaving between East and West towards the dawn of the Day After.