Taxes, Royalties, and Idea Generation

Taxes, Royalties, and Idea Generation

-

Author : The BlackSummit Team

Date : January 12, 2021

“The best business is a royalty on the growth of others, requiring little capital itself.” – Warren Buffett

“Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.” – Leonardo da Vinci

Leverage does wonders to a business, both on the way up and the way down. We see it reflected at both the operational level as well as the pricing of risk assets. Take the selloff during the depths of the Coronavirus last spring as an example. The most devastated businesses were those with considerable operating leverage, assets and costs that could only marginally be cut with any discretion.

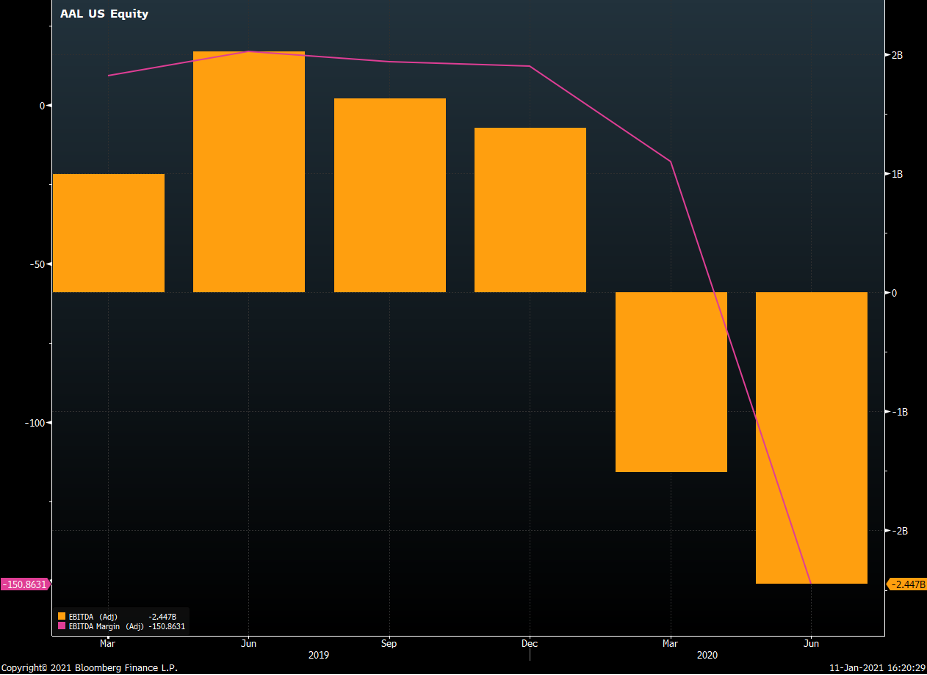

Take airlines for instance. With a high percentage of costs fixed, incremental swings in revenue have amplified effects on the profitability and cash generation of the business. American Airlines, for example, generated roughly $1 billion and $2 billion of EBITDA respectively in the first two quarters of 2019 (with margins about 9% and 17%). But with travel suspended last year there were no sales to support its cost base. The company cut what it could but those efforts could only go so far. As a result, in the first two quarters of 2020 American generated about -$1.5 billion and -$2.5 billion of EBITDA (with margins reaching -150% in Q2) (Figure 1). This is a massive swing from one year to the next, no doubt due to unique circumstances, but similar patterns are apparent throughout its history, and those businesses with a high degree of operating leverage. Financial leverage, of course, has similar effects. Firms with higher amounts of debt and interest expense have tougher times relative to other businesses, ceteris paribus.

Figure 1: American Airlines As an Example of High Operating Leverage

But for a small proportion of businesses there is a way to enjoy the benefits of debt without having to bear the vast majority of expense and risks directly and that is to ride the coattails of another company’s investments. Another way to put is to be in the business of selling blades and letting other companies worry about selling razors.

It’s a trend that is apparent throughout history, particularly with the standardization of new technologies. IBM birthed the modern computing industry decades ago. In the process of it expanding the distribution of PCs to more and more people with its global salesforce Microsoft was able to ride in right behind IBM and capture incremental profits in a cheap manner. Consider that in 1986, according to John Huber (who deserves credit for motivating this post), Microsoft earned $39 million in profit on $50 million of invested capital. Over the ensuing 13 years the company invested an additional $250 million and generated $2.2 billion in profits. That’s a return of over 800% for Microsoft’s investments. The company didn’t need to spend much to achieve that growth because it was following the investments laid out for it made by someone else. Basically, for every PC sold Microsoft made a royalty. And given that the marginal cost of a piece of software is practically zero, each additional royalty could fall straight to the bottom line.

The examples are plentiful. Apple has benefited tremendously from the capex of ATT and others but didn’t have to take up tremendous levels of debt like the telecom providers did. They benefitted from the debt of others. Facebook and Google are similar in that they rode behind investments of ubiquitous communication. Hotels, like Wyndham, and restaurant chains who rely on a franchise system employ a similar model. They use some amount of capital to start up but incremental transactions do not rely upon deploying capital. Instead, they collect coupons on the work and effort of their franchisees. Something similar could be said for the payment networks, Visa and Mastercard, two of the best businesses I’ve come across. The growth of commerce, offline but especially online, has been booming for several years with a long runway ahead. Whether it’s retailers like Amazon or other players in the ecosystem (like Shopify, PayPal, Fiserv, and many others) as ecommerce proliferates the majority of payments flow through the networks these two set up decades ago. In essence, the networks get to tax global consumption with each marginal transaction essentially being pure profit.

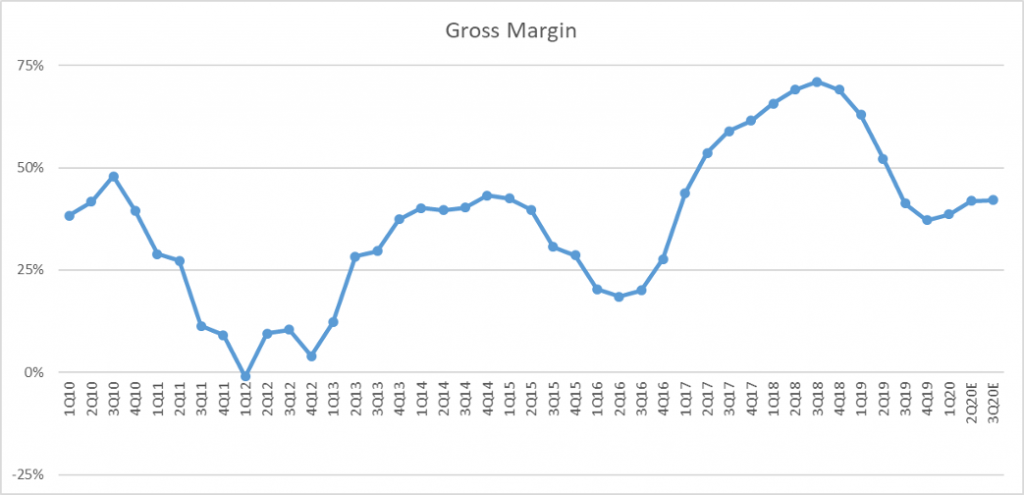

While a simple framework, simple does not equal easy. Far too often investors are quick to overlook some of the prerequisites for what makes investing in these types of businesses valuable, instead opting for anything that will grow because of an invention or new technology. For one, the presence of a moat is either ignored or brushed aside too quickly. For example, with data intensity growing by leaps and bounds many investors have been drawn to the memory industry as a way to get exposure. Increased data means a greater demand for memory for computing but the commodity like nature of memory means Gross Margins are extremely volatile (Figure 2). The lack of moat puts these firms at the very tip of a bullwhip, at the mercy of momentum gone before it.

Figure 2: Micron’s Gross Margin

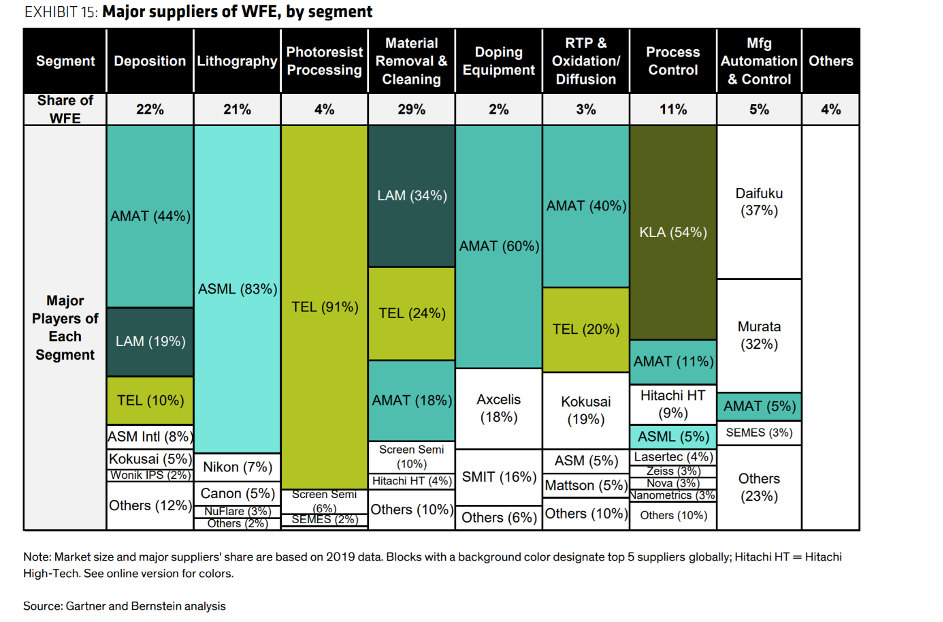

Looking a bit deeper and thinking a little harder would save these investors a lot of stress. Regardless of which firm designs memory chips (or any chip for that matter) they must get manufactured somewhere. And odds are it’ll be made using tools from one of a handful of oligopolists. Further, given the extensive, and rising, complexity of manufacturing these firms have come to dominate specific portions of the process, not encroaching on each other’s domain (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Equipment for Building Semiconductors Comes From An Oligopoly, Bernstein

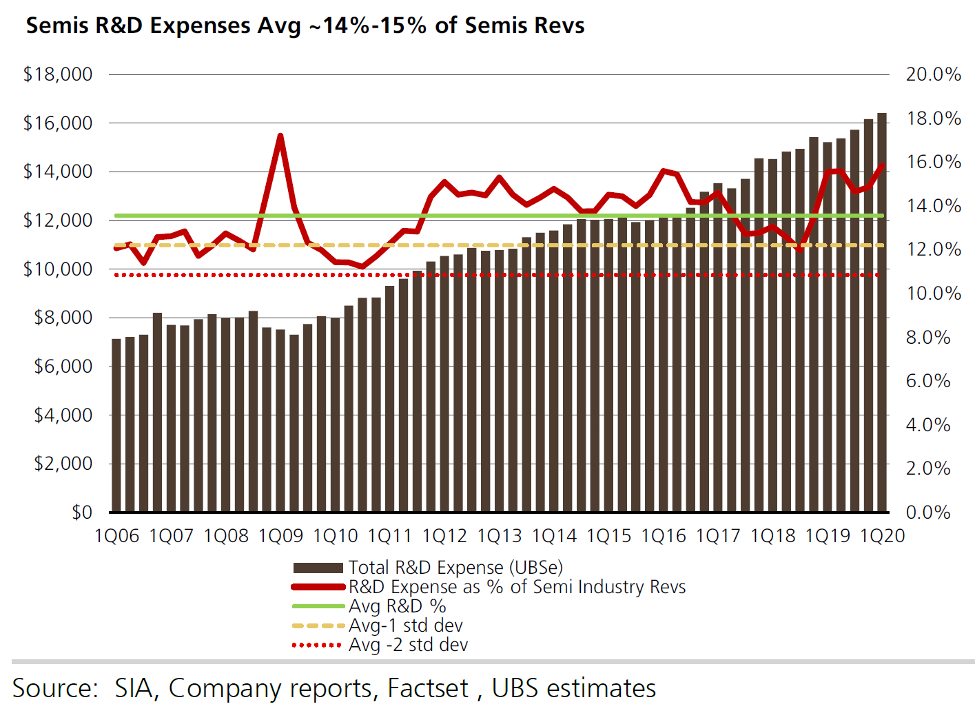

But we can go even further and deeper with this example. Because before a chip gets constructed with one of these tools it is designed years in advance via the R&D budgets of the giant design firms across the globe, like Intel, Nvidia, Samsung, Apple, Qualcomm, and more. And the R&D budgets of these firms are far more stable with consistent growth than the cyclical nature of orders for equipment. While all these aforementioned firms have considerable intellectual property, they would be nowhere without the essential Electronic Design Automation software offered by firms like Cadence Design and Synopsys, the recipient of a substantial portion of those R&D budgets.

Figure 4: The R&D Budgets of Semis Is Extremely Steady, UBS

It’s no wonder then that EDA firms have outperformed equipment firms and Semiconductor stocks over the last decade; they’re the ones collecting the royalty on the propagation of chips and digitization that’s occurred (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Tracking Performance: EDA (Yellow) > Equipment (Orange) > Semiconductors (White & Red)

None of the above should constitute detailed security analysis or a recommendation but it does demonstrate a way to break down a pool of profit, how it’s divided up among players and the associated risks between connected industries.

It also helps serve as a filter for new technologies and innovations. Are they really disruptive or will they be paying royalties on the same providers as so many other companies? As the saying goes, the more things change the more they stay the same.