SPACs: Sponsor Revolution or PIPE Dream

SPACs: Sponsor Revolution or PIPE Dream

-

Author : The BlackSummit Team

Date : December 8, 2020

“Corporations get the shareholders they deserve.”

– Warren Buffett

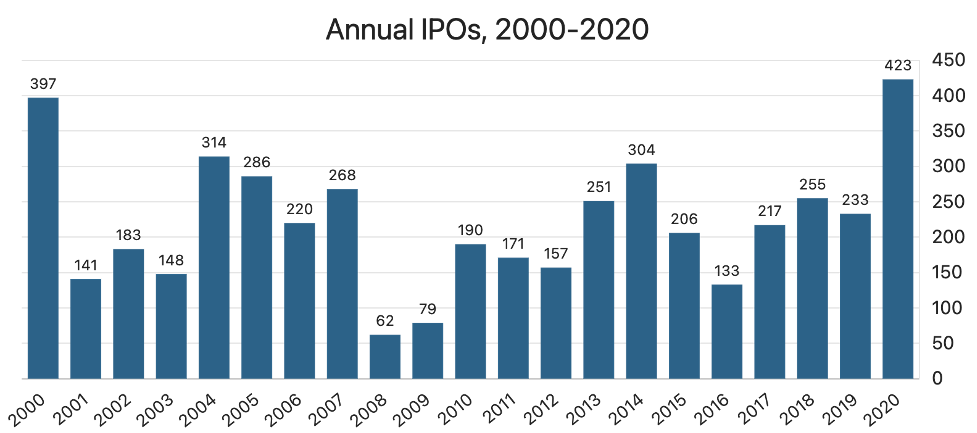

With valuations at cycle highs there is no shortage of analogies to compare the market today to its past peaks. The virality of young tech stocks, a surge of retail investors joining the market for the first time, and the number of IPOs are all frequently used anecdotes to denote the state of the market as exuberant (Figure 1). Innovative financing vehicles is another such marker frequently associated with topics and if 2020 can be synonymous with anything in the world of finance it would be the SPAC.

Figure 1: The Number of IPOs in 2020 Surpasses All Prior Years

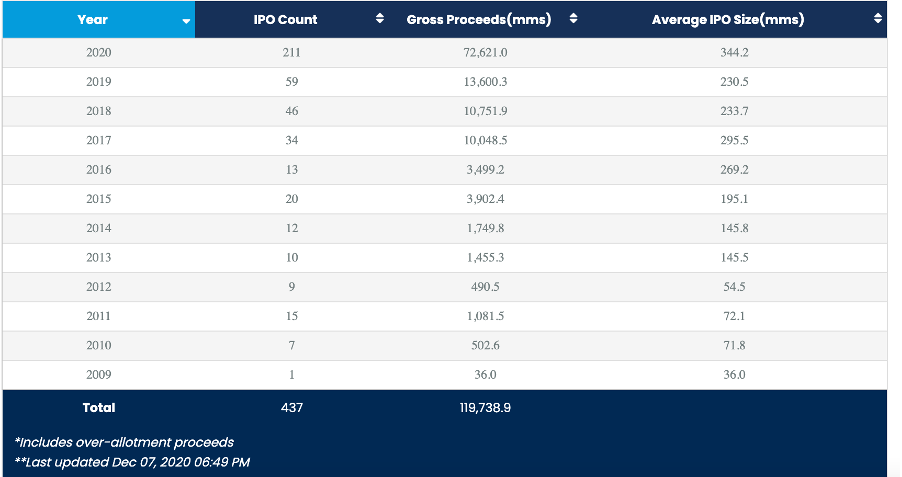

SPACs, short for Special Purpose Acquisition Vehicles, are not exactly a brand new entity in public markets but their presence this year dwarfs anything we’ve seen in recent market history. SPAC IPOs account for 50% of new offerings in the market. As for capital raised, whereas the pre-Financial Crisis high for SPAC proceeds was approximately $10 billion in 2007, 2020 has seen over $70 billion already raised, greater than the cumulative amounts raised from 2009-2019 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: 2020 SPAC Proceeds Have Blown Away Prior Years, SPAC Insider

So, what is the reason behind such a phenomenon this year? I can think of a few, comprising of both macro and micro reasons.

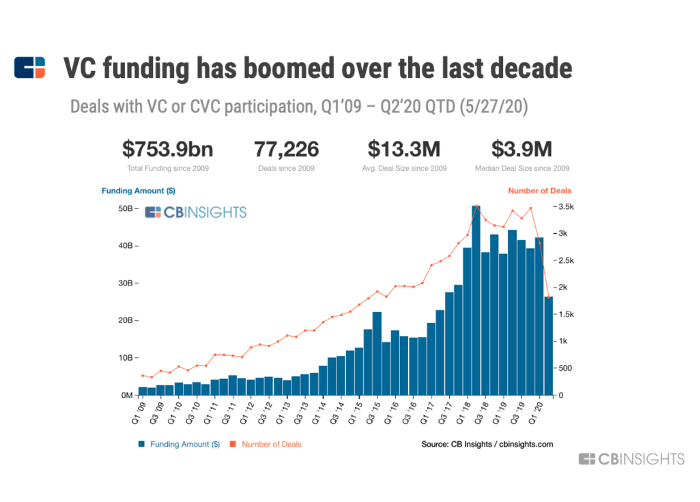

From a macro perspective, the private markets have seen enormous inflows of capital and business formation over the last decade (Figure 3). The ease of opening a new business continues to fall thanks to the development and proliferation of new technologies. In a virtuous cycle, plentiful capital, enabled by a decade of historically low rates, flooded private markets, encouraging new businesses to start, expand, and build up record private market valuations. By early 2016, over 220 companies had reached the vaunted “unicorn” status according to Fortune magazine.

Figure 3: Venture Funding Exploded Over the Last 10 Years

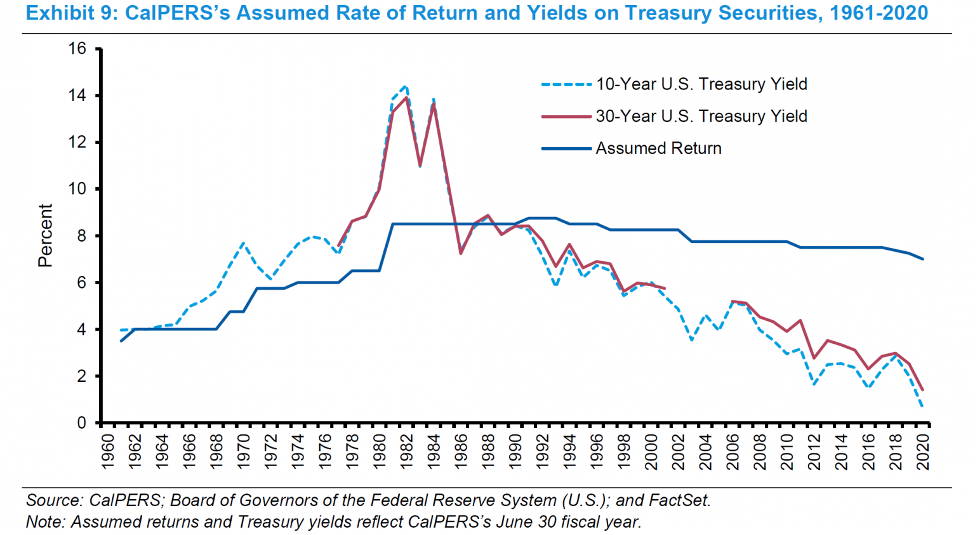

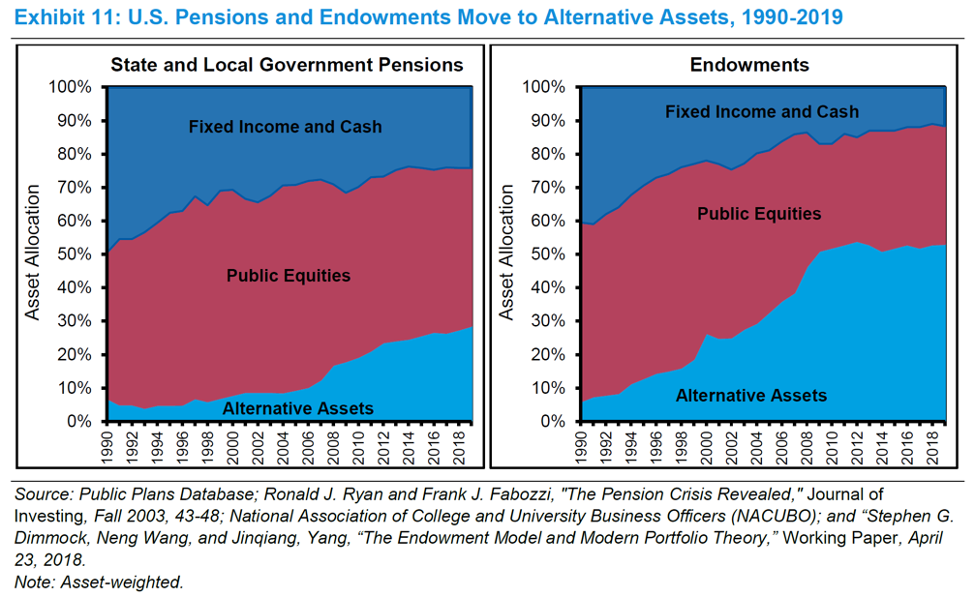

Concurrently, the investing landscape has seen some of the world’s largest investors, pension funds and endowments, broadening out their scope for deploying capital. Both, earning low returns on fixed-income allocations, have continued to reach for return in order to meet their lofty assumed rate of return targets (Figure 4). As a result, allocations to Alternative investments have continued to rise (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Assumed Rates of Return Remain High…Leading to Greater Alternatives Investment

From a micro perspective, life for a private company has been pretty comfortable for several years, able to leverage the above conditions to extract high amounts of capital at generous terms to chase growth without any demand that these companies show profits or sustainable cash flow. The result was that companies stayed private longer than ever before. Uber, for example, stayed private for 10 years, much longer than other darling private companies like Facebook (8 years), Google (6 years), and Amazon (4 years).

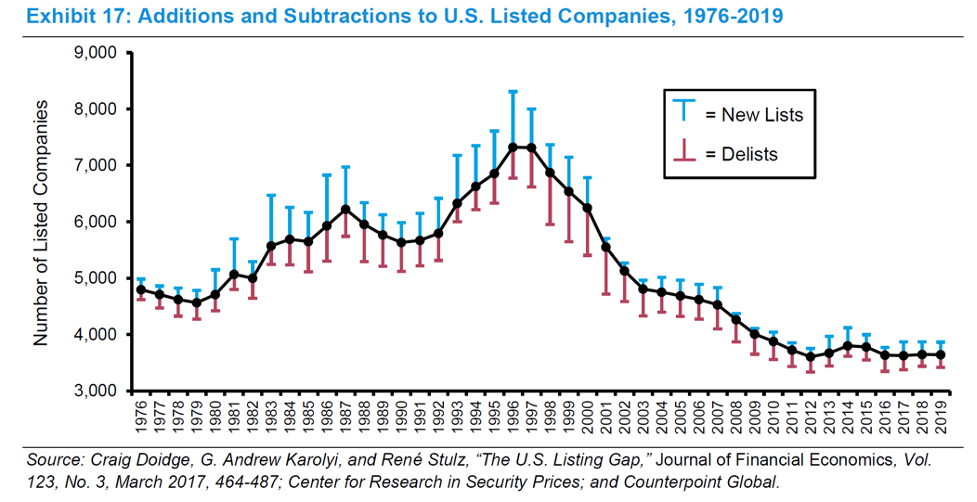

What’s fascinating is that one would think with such massive amounts of capital invested the ability and desire to get out, go public, and bank a return would be high. After all, the public markets still trounce the private ones in size and if more capital is needed the public markets may be the place to get it, especially given the public markets’ dwindling number of investment options over the lats few decades (Figure 5).

Figure 5: A Scarcity of Companies

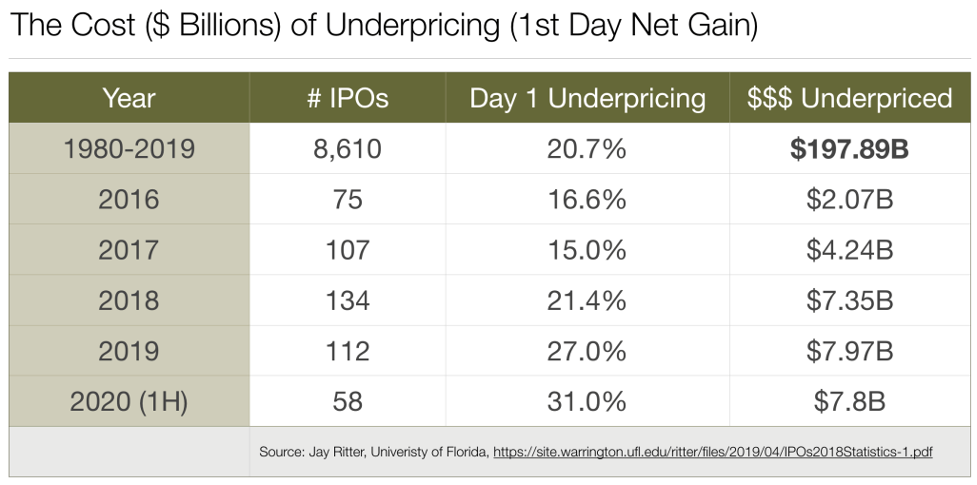

That has not been the case however. For a number of reasons such as, a spike in startup failures in 2016, the Theranos scandal, “dirty” term sheets, and more, capital became, for all intents and purposes, trapped. The most dramatic reason however, has been the massive underpricings, of the IPO market (Figure 6).

Figure 6: IPO Underpricings

Over the last couple of decades the classic “IPO pop” has morphed into a pretty enormous wealth transfer from private companies to the most privileged of investors, those with the largest paychecks and balances who are good for driving the largest commissions to investment banks. These customers are essentially gifted underpriced stock via investment banks and get to turn around and sell it the following morning for a profit of ~31% this year. A better explanation can be found here thanks to Bill Gurley. But to me, with the amount of dollars invested at stake, it doesn’t surprise me that a mounting problem of IPO underpricing and distorted incentives drives both private companies and their earliest backers into another vehicle.

Enter the SPAC.

In a SPAC, rather than the private company itself raising equity a group of investors/sponsors come to the equity market raising funds with the stated intent of buying a private company later on, usually within two years. Cash raised from investors is deposited into an escrow account, earning interest, while the sponsors seek out a target. If no acquisition is made, funds are returned to investors along with a pro-rata portion of interest or a vote takes place to extend the life of the SPAC. When an agreement with a target company is reached, the largest institutional investors provide remaining financing to get the deal closed. Investors who don’t like the deal, can turn in their shares and get their principal back.

The advantages over IPOs are the SPACs cheaper cost of capital (by avoiding the underpricing in an IPO), a faster route to market (two months compared to six on average) and the ability to negotiate terms directly with the SPAC’s sponsor, maintain some control of the process of becoming public. Further, unlike a Direct Listing (used by firms such as Slack and Spotify) capital can be raised in a SPAC for investment purposes.

What attempts to be a win-win-win for all parties (investors, sponsors and the target) is a bit more complicated however underneath the surface. For one, Sponsors, often some of the most famed and privileged investors, get entitled to a “promote,” representing 20% of the acquired company’s common stock for a total fee of just $25,000. Thus, for example, on a position instantly worth $40 million once an agreement is reached, even a 50% decline in share value once the deal is consummated leaves Sponsors with a return of roughly 800x. This creates egregious conflicts of interests between sponsors of the SPAC and investors along for the ride. What is allegedly equal classes of stock in actuality behaves as anything but. Sponsors are thus incentivized to get a deal done regardless of the quality of the underlying company because of the asymmetry inherent in getting a deal done. In fact, due to the fixed nature of the promote, Sponsors have an incentive to overpay. The higher price tag for the acquisition increases their returns. Further, Sponsors frequently use closely held companies to serve as “advisers” throughout the merger process, charging fees to the SPAC. It’s no wonder we end up with situations like Nikola, an “electric truck” company with a grand total of $36,000 not from selling trucks or technology, but for installing solar panels in the home of its executive chairman. Unfortunately, Nikola is far from the only SPAC target of dubious quality.

Second, institutional investors, who provide the balance of the financing to complete the deal after a SPAC is raised but before a merger is completed via a PIPE (Private Investment in Public Equity) frequently do so on terms advantageous to them. Whether it’s winning a concession of preferred stock, warrants on the new company or some other preferential treatment, institutional investors eventually embed themselves as a class of stock with rights better than the common shareholder.

And for that common shareholder, not only do they not see any sort of excess returns like the sponsor or institutional class, they end up with a share class that gets diluted if they’re not careful via the PIPE.

The average SPAC since 2015 has a loss of 18% (and a median loss of 36%). And yet, despite the results and the conflicts of interest I suspect SPACs are here to stay. For one, thankfully, over the last few months SPAC sponsors have started to compete with each other, offering terms better for companies as well as investors. One SPAC, Bill Ackman’s Pershing Square Tontine, even reduced the promote to zero and locked in their capital for a minimum of 3 years, putting more skin in the game than anyone else has so far. And with so many SPACs available, companies can pick and choose the right partner. Second, the phenomenon of trapped capital in Silicon Valley and the failings of the IPO are all too real and costly. Third, the dynamics of high return assumptions and rising allocations to Alternatives will only accelerate in the future. Finally, we are still so early in this new game, despite the flood of capital that has entered, that competition between SPACs and repetition will create standard practices that are more transparent. Things like audited historical financials will be made public sooner, lower rates of promote will become the norm, and in the meantime innovation for fund structure will remain.

The ultimate lesson is that incentives and stewardship matter. That’s the whole points behind my many commentaries on Return on Invested Capital: why it matters, where it comes from and how to identify its sustainability. And that’s ultimately the point behind the Buffett quote that leads off this piece. Companies that manage for the short-term or obfuscate their business dynamics or play accounting games give shareholders every reason to sell their shares for non-fundamental reasons. When it comes to SPACs however, the set-up is such that it is common investors entrusting privileged ones, but the lesson remains. Partner with the wrong one and you could be on the painful end.