“On Monday, March 10, the rumor started: Bear Stearns was having liquidity problems.” 15 years later to the day, the FDIC would put Silicon Valley Bank in receivership, marking the second largest bank failure in U.S. history and sending financial markets to reexamine the stability of the banking industry once again.

The flashbacks to the GFC are understandable; banks this big don’t go bankrupt every day. Nor do they fail so quickly. While Silicon Valley Bank’s demise has traits that mirror Bear Stearns’ (chronicled in this piece from Vanity Fair) and bank stocks have bled for the past few sessions, the events of the past week are more idiosyncratic than systemic.

1. The Quality of the Assets Was Not the Issue

One of the most important aspects that distinguished the stress in the banking sector this past week was how it started. In 2008, whether with the giant investment banks like Lehman and Bear Stearns or the more commercial-oriented ones like Washington Mutual, it was the dubious quality of the assets that saw investors liquidate exposure as fast as possible. Specifically, paper issued and traded (MBS, CDOs, CDO-squared, and every other rehypothecation of the same cash flows over and over) never deserved the valuation it received from the start; the core economics did not match up with the value of the paper. Once the pricing of securities started to match that underlying value the game was up.

But that is not how issues started at Silicon Valley Bank. This wasn’t a story of questionable loans or securities that didn’t hold their weight. The bank parked the majority (over 95% per its Balance Sheet as of Dec 31, 2022) of its deposits into US Treasuries and Agency bonds that are backed by the federal government.

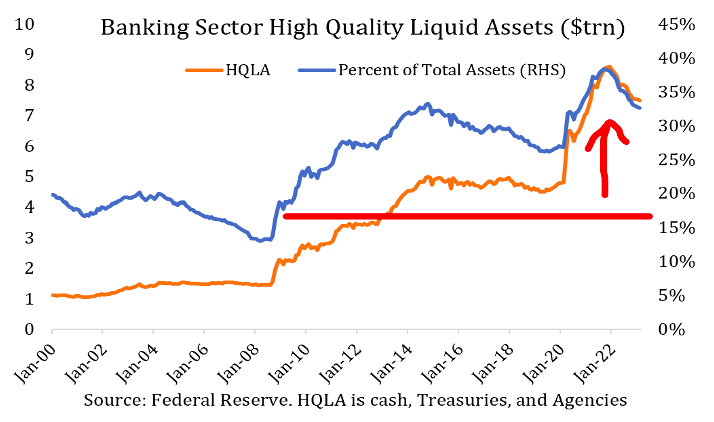

While every investment has some form of risk, credit risk wasn’t the concern here. The banking sector in large isn’t anywhere close to the kind of position it was in 15 years ago. High-quality assets, namely Treasuries and government-backed agency securities are a much greater mix of balance sheets now compared to then (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Asset Quality Is Much Better Than Pre-GFC, Source: Joseph Wang

2. So What Was the Issue?

What plagued Silicon Valley Bank is much closer to the classic bank run one sees while watching It’s A Wonderful Life every Christmas than the sort of credit freeze witnessed during 2007-2009. But first, some context.

Silicon Valley has positioned itself as the preeminent financial institution serving venture capitalists, nascent tech companies, and high-net-worth individuals. It developed a specialty around an industry that 40 years ago when SIVB was founded, was not something a lot of bankers wanted to touch because of unfamiliarity, unique attributes, newness, and other traits. But the competency and relationships SIVB built served them well. The stock compounded over 18%, in line with the Nasdaq, from the Financial Crisis to two Fridays ago, which includes the stock getting cut in half before the events of last week.

As much as tech has become a dominant sector within the public markets, its role in private markets is even greater and no bank stood to benefit more from that trend than Silicon Valley Bank. That is even more so the case in the boom sparked by the Covid recovery. Everything tech-oriented and tech-adjacent saw booming valuations, easy funding rounds, and business plans approved regardless of how cash burning or flimsy the economic case was. Funding poured into the Valley in order to finance and bring forward a digital transformation years ahead of schedule. The cash poured into venture and tech companies who deposited it at SIVB; since 2019 deposits at the bank tripled while across the industry they only rose 37% during the same period.

Figure 2: Deposits Have Tripled at SIVB Since 2019, Source: Joseph Politano

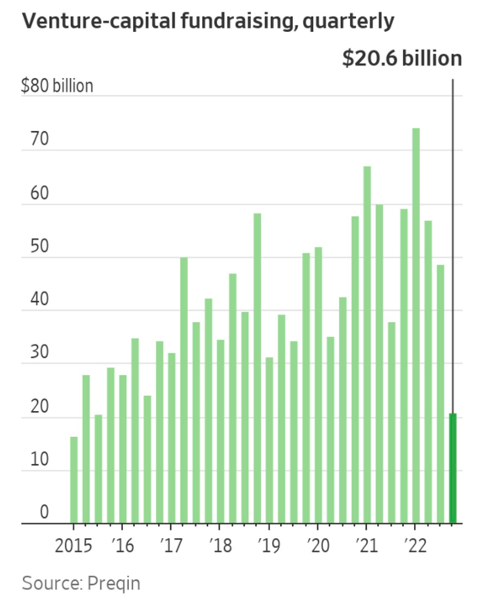

But after the Covid boom came the Covid bust where the biggest losers have unquestionably been the most speculative and economically dubious companies. Goldman’s Unprofitable Tech Index tells the story well (Figure 3). It’s no surprise then that VC fundraising across the market fell off a cliff (Figure 4).

Figure 3: The Unprofitable Tech Burst, Source: Goldman Sachs

Figure 4: VC Funding Last Q Was Lowest in Almost a Decade, Source: WSJ

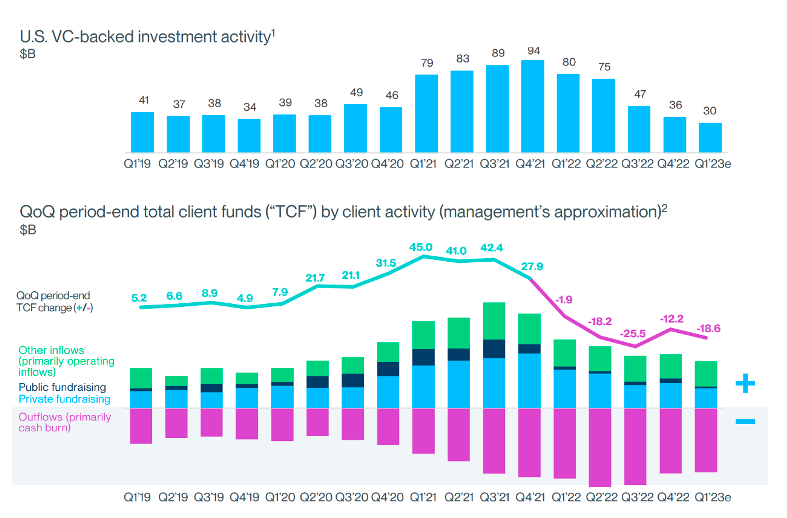

A slowdown in VC fundraising meant fresh deposits weren’t coming in to replenish SIVB. And cash burn remained extremely elevated. Per an investor presentation from management last week cash burn from SIVB’s clients was still twice as high as pre-2021 levels and VC funding was due to fall an additional 15-20% from last quarter (i.e. from already depressed levels).

Figure 5: Companies Continued to Burn Cash While New Funds Weren’t Coming in Fast Enough, Source: SIVB

SIVB wasn’t the only institution to see deposits moving out the door, however. Essentially every financial institution has seen its deposit base contract as interest rates have moved up while rates on deposits have trailed substantially. The national average yield on a savings account is just 33 basis points. Meanwhile, 3-month T bills offer over 4.5% annualized. The draw for deposits is obvious: move money out of bank accounts yielding barely anything and into Treasury securities.

SIVB management determined the imbalance between inflows and outflows of funds required some sort of action. The bank announced that it would sell $21B of securities off its books (marked as Available for Sale (AFS) on its Balance Sheet) but would do so at a loss of $1.8B. All of the bonds it had purchased with the surge of deposits had fallen in market value due to rising rates all across the bond market; a sale of common and preferred shares would occur as well in order to shore up its capital position following the loss.

The mere announcement of the sale of its AFS book and share price surprised investors, analysts, and customers despite the fact that with the move to sell the securities and raise equity SIVB was in a stronger financial position. But emotions took over, with VCs recommending their companies to withdraw cash because “there was no downside to removing their money from the bank.” The next day $42B was taken out of SIVB as fear spread from one firm and one VC to the next, without ever giving a second thought to the self-fulfilling stampede they were causing. Hysteria took over. Everyone went for the door at the same time and by mid-day Friday, the FDIC had closed the bank and put it in receivership.

3. What Could Have Been Done?

First, and perhaps most importantly, there’s been a surprising and disappointing amount of discourse stating that where SIVB erred was in borrowing short and lending long. This, we would point out, is the very definition of a bank; it is the nature of the business model. To point to this as an issue is to point a finger at all banks. Further, not a single bank is set up or could be set up to survive a full-fledged spontaneous bank run. Human emotion and psychology cannot be hedged away.

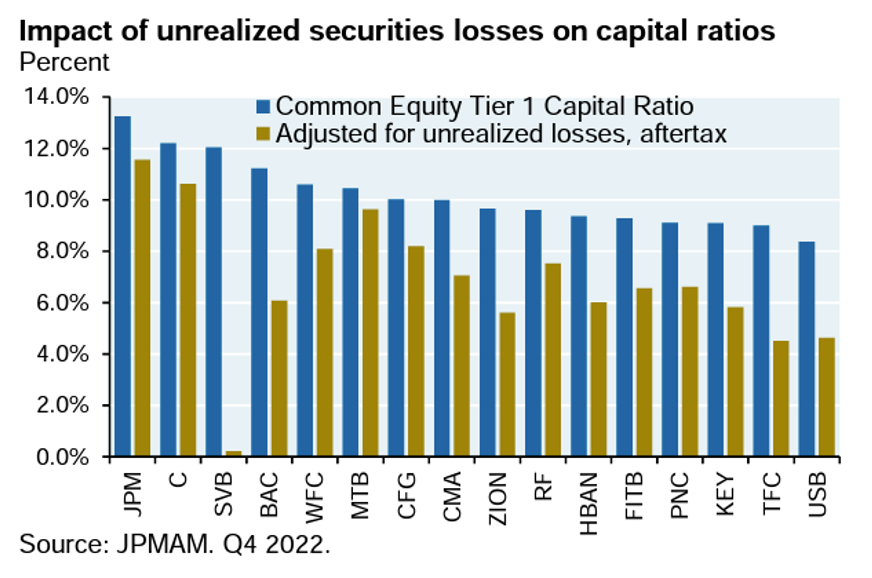

In the aftermath of SIVB’s demise, much has been made about the banking industry sitting on huge amounts of unrealized losses on its bond portfolios. Advocates for a bailout of SIVB pointed to these unrealized losses as a way to acquit management from the position of being responsible for the bank’s failure or to prevent the run on Silicon Valley from spreading to other banks. But the further anyone digs into SIVB over the last couple of years, the more apparent that the distinguishing characteristics of the bank were ones of mismanagement, particularly with regard to risk.

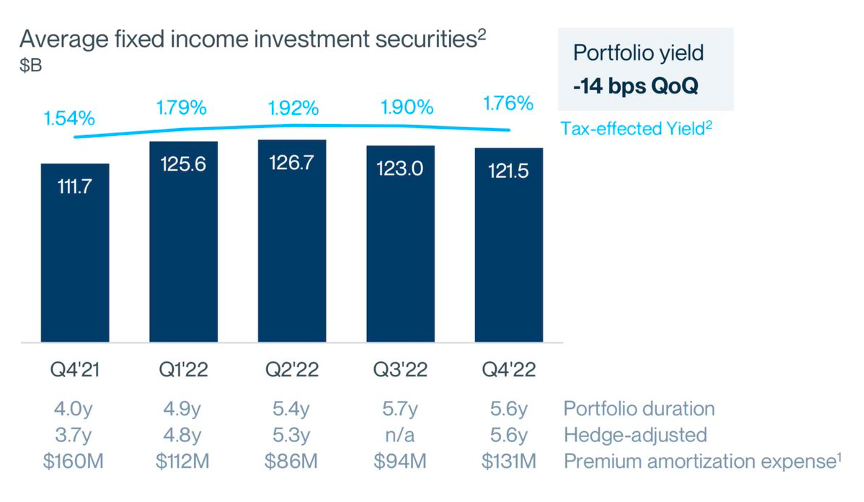

Banking 101 is about matching up assets and liabilities so that your duration exposure on either side of the balance sheet is not imbalanced from the other. But with VC funding being the dominant vertical served, SIVB had to know the deposits sitting in its accounts weren’t destined to be long-term liabilities. Yet most of its assets were put in longer-duration Treasuries and MBS. While these instruments bore little credit risk as discussed above, they did possess substantial duration risk if rates rose. Some duration is ok, but too much could be a death sentence with a deposit base that is expected to be withdrawn so that venture companies can cover things like payroll and operating expenses. Further, virtually none of the portfolio was hedged from interest rate risk; the duration of the portfolio and account for hedges is essentially the same as of December 31 (Figure 6).

Figure 6: SIVB Essentially Didn’t Hedge Interest Rate Risk, Source: Brandon Carl

A counterpoint to the hedging argument is that by entering into an IR swap, SIVB would essentially be foregoing any return. To that I would say if the goal is to make money on the direction of bond prices they should be a hedge fund; some level of hedging to line up with the deposit base would be prudent.

Further, inflation has been the biggest macroeconomic story of the past year or so and anyone with a Bloomberg terminal could have told you the direction monetary policy was headed with the way inflation data was coming in. And yet, as shown in Figure 6, the bank continued to increase its duration quarter after quarter.

Second, other banks saw this risk and made cautious and calculated decisions to watch their duration exposure. Instead of reaching for yield by moving further out in time or buying riskier debt, M&T Bank made the astute observation that if they were wrong, an equity raise would squash any extra yield picked up. Instead of reaching for yield, they parked more funds at the Fed. M&T’s wisdom is clearly evident in Figure 7 and in stark contrast to SIVB. While Figure 7 clearly shows there would be a notable impact on the capital position of the banking sector if unrealized losses were considered, SIVB clearly stands out unique in the management of its portfolio.

Figure 7: One of These Is Not Like the Other, Source: JP Morgan

It’s also reasonable to infer that SIVB management was having liquidity issues last year and was taking notable steps to secure cash. Over $55B of its securities had been pledged for cash as of year-end last year. That includes $15B in borrowing – roughly equal to their equity capital – from the San Francisco Federal Home Loan Bank, the lender of next-to-last resort. If it knew of cash flow and mismatch issues two quarters ago, then there was ample time to secure an equity raise long before deposit outflows got even worse. But there’s no guarantee that would have gone smoothly either. After all, Silicon Valley also completely bungled the attempted equity raise last week (which failed to go through due to price pressure). Normally when a company issues secondary shares, they wait to make the announcement of the share sale until after financing is secured with their bankers. That’s not what happened in this case. The bank hadn’t done the necessary paperwork to get confidential commitments from investors and did not have pricing secured.

4. Did it Need a Bailout?

Sunday night, a joint statement from the Treasury, Federal Reserve, and the FDIC announced that depositors would have access to all of their funds the next day, even those above the previous FDIC-insured limit of up to $250,000. Any shortfall from the FDIC’s Deposit Insurance Fund would be recovered by levies on banks as opposed to taxpayer funds. So, depositors have been made whole at SIVB (as well as at Signature Bank of NY which went into receivership on Sunday) while equity and debt holders have been wiped out. A new credit facility by the Fed was created, and backstopped by the Treasury, to extend credit to regional banks against collateral at full par value. The actions constitute a bailout but not exactly in the same terms as what we saw in 2008. There is no federal ownership of a bank. There is no TARP. Taxpayer funds aren’t being used to support stocks. But it still represents public authorities influencing events to prevent the full pain induced by the private sector. It’s clear based on press reports that the FDIC, Fed, and Treasury all preferred a buyer to step up and purchase the bank while guaranteeing all deposits, but that option didn’t materialize in time.

Did it have to happen this way? That’s all speculation and conjecture but I don’t think the full-fledged fear-mongering scenario projected by some would have played out had this plan not come together. In addition, plenty of commentators and self-proclaimed sophisticated businesspersons have been disingenuous with what the worst-case scenario would have been; there was zero chance all uninsured deposits would have been lost. In fact, there are plenty of credible and plausible scenarios by which 80% more of uninsured deposits would have fully paid out. Maybe not all at once, but enough capital would have been available Monday morning so that business could resume for all stakeholders. There’s been a documented process by which banks go under and that process should have been allowed to play out barring some collection of evidence that suggested the contagion potential was that severe.

Presumably, this was done to prevent a wave of bank runs from ensuing first thing Monday morning across the country. How likely that threat was can’t be known but the hysterics by many over the weekend certainly weren’t helping to calm the situation down. For whatever it’s worth, several major regional bank CEOs said they were not seeing unusual withdrawal activity on Monday. Whether that would have happened without these actions is a counterfactual no one can prove.