Instead of attempting to cover all areas of emerging markets in one report, we are going to split them over several weeks and cover specific countries. This week we will cover Southeast Asia, focusing specifically on Thailand and Indonesia.

Thailand

Thailand was almost entirely agricultural prior to 1980, but from then until 2014, it has been adding in both manufacturing and service sectors. In that interval between 1980 and 2014, the GDP grew at about 6% per year. The growth rate has cooled since 2014, slowing down to 3.7% y.o.y. growth in 2017.

Where Thailand is going from here depends on who you ask. The World Bank is optimistic and has forecast GDP growth in 2018 to be 4.1%.. A number of factors point in an optimistic direction:

- The government’s implementation of a 20-year national strategy to develop competitiveness, implement tax incentives, and build infrastructure and the digital economy.

- Consumption is approximately 50% of GDP.

- Consumer confidence is high.

- The Bank of Thailand’s leading indicators are positive.

- The Ease of Doing Business index has risen to 26.

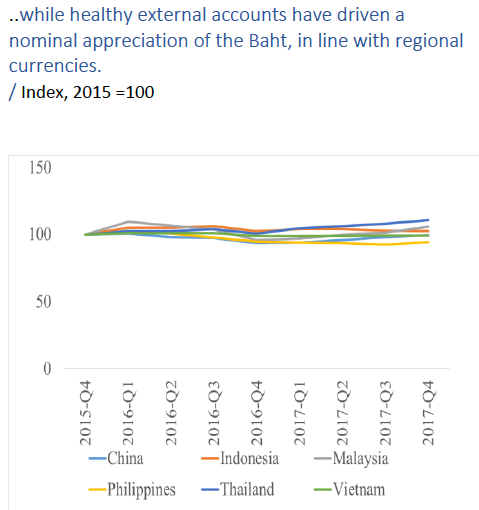

While the World Bank noted that the Thai baht has appreciated over the past year, it is described as a “nominal appreciation” and shown in a graph that seems designed to disguise the fact that it was a 9% increase last year.

Investment banks paint a more nuanced picture of Thailand, noting that imports and tourism are major portions of the GDP, and while the appreciation in the baht has not diminished the amounts of either, both are going to feel the effects soon. The politics of the country are unsettled in the aftermath a military coup in May 2014 that overthrew a popular, but flawed, reformer. The king and military have unchecked power, and though no one describes the environment as repressive, the Freedom House Index for Thailand is Not Free. Elections scheduled for later this year have been postponed until 2019, adding uncertainty.

Investment banks note the following obstacles to Thailand’s growth:

- Wages are generally weak.

- Corporate and household debt burdens are high.

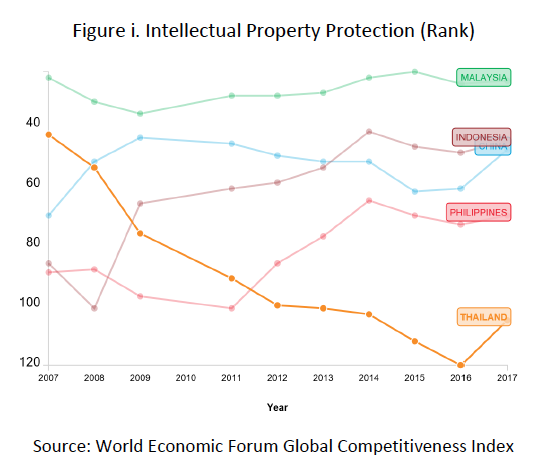

- The protection of intellectual property is weak.

The reality, then, is that Thailand has genuine potential for growth, but has work to do in order to accomplish it. This is well-illustrated in the following graph. (For comparison, the blue line whose label is mostly covered is China.)

Indonesia

Indonesia is generally considered a Big Emerging Market. It is a member of G-20 and is famous for the (mostly) peaceful coexistence of a moderate Muslim majority (87.2%) and a Christian minority (9.9%).

Indonesia’s GDP grew 5.0% in 2016 and 5.1% in 2017. The projections for the next two years, according to the Institute for Economic and Social Research (an Indonesian think tank) are GDP growth of 5.3% in 2018 and 5.5% in 2019. Several factors support the projection for Indonesia’s increased growth of GDP over the next few years:

- There has been a steady increase in disposable income.

- E-commerce is increasing.

- Inflation has been low, despite a major increase in electricity costs.

- Bank Indonesia (the central bank) has cut rates eight times in the past two years but has said that no more rate cuts are planned.

- President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo has put infrastructure construction as a flagship agenda item.

- Manufacturing created 1.5 million new jobs in 2017, mostly absorbing the loss of jobs in the agricultural sector.

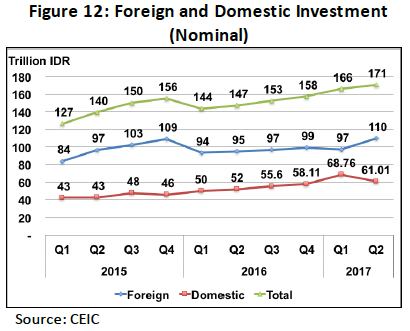

- Foreign direct investment was at a seven-year high in 2017. Recent changes in foreign and domestic investment are shown below.

But, as always, there are factors that are pushing against growth. In this case, a critical element is consumer spending. Household consumption needs to remain steady or grow slowly; otherwise corporate taxes will decline, putting pressure on the government to increase spending. The government deficit, currently at 2.92% of GDP, is just below the mandated limit of 3%. Thus there is little room for extra government help unless other projects, such as the infrastructure construction, are delayed, which turns into a vicious cycle.

Another factor that could slow down growth of Indonesia’s economy is the potential rise in global protectionism. Exports are a large portion of Indonesia’s GDP, and a global trade war would hamper growth seriously both by decreasing exports and by causing a manufacturing slowdown.

The hope, then, is for exports to increase and for foreign direct investment to continue its upward trend. Indonesia can encourage investment by creating incentives for private sources of funding for some of the infrastructure projects and by enforcing contracts more consistently. This would encourage both foreign and domestic investment. In that case, the crunch that might otherwise occur will be avoided.