Removing Friction

Removing Friction

-

Author : Joel Charalambakis

Date : August 24, 2021

“You need a different checklist and different mental models for different companies. I can never make it easy by saying, “Here are three things.” You have to derive it yourself to ingrain it in your head for the rest of your life.”

“Take a simple idea and take it seriously.”

“The more basic knowledge you have, the less knowledge you have to get.”

-Charlie Munger

Charlie Munger gave a speech at Harvard University in 1995 that encapsulated much of what would be published in the fields of behavioral psychology and behavioral finance over the following decades. His distillation of 24 standard causes of misjudgment should be required reading for anyone, regardless of their interest in the world of investing. Especially since his remedy to diminish risk calls for drawing upon an entirety of faculties: from physics, to biology, to psychology, to statistics, and deeply rich in historical parallels. Munger has long preached that by sticking with and applying the most basic tenets of multiple disciplines one can construct mental models of the world and navigate it with prudence.

While far less consequential and virtuous than finding wisdom in a complex world there are templates of business models that transcend industry or sector, stand the test of time, and can help investors concentrate their time and energy on the most worthwhile opportunities.

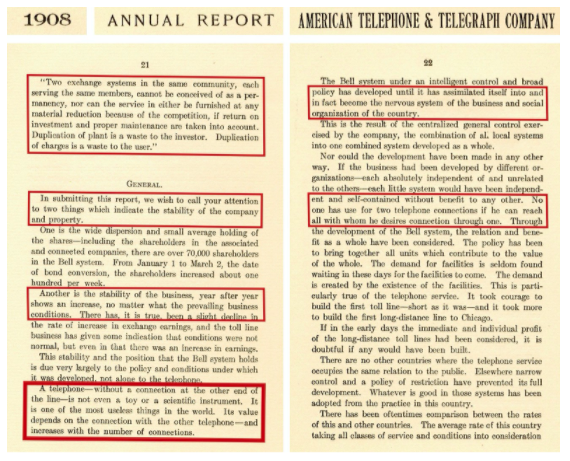

Take, for instance, the presence of network effects in a product or service. These businesses can be identified whereby the product or service offers greater utility to users as more and more people join. After reaching a critical mass these businesses see adoption take off and growth can accelerate even at later points in a company’s life. Companies (industries/services) like Facebook (advertising), Visa (payments), Google (search), eBay (eCommerce), and others all are predicated on operating a successful network. But it’s not just new age industries that rely on such a model. AT&T openly recognized the importance of the whole network in 1908 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Network Effects As A Foundation Are Not New

Many of these mental business models are well known: brand strength, toll roads, low-cost providers, etc. They are frequent foundations for a differentiated business. One such pattern, that seems to get less notice, is companies that abstract away unnecessary tasks or complexities on behalf of their customers. Sometimes they may actually take on extra costs that aren’t absolutely necessary because it allows them to serve their own customers by making the latter’s life easier.

Take Geberit, the European leader in products used for flushing toilets. They differentiate themselves and stand apart from competitors by undertaking their customers’ (plumbers in this case) interests as their own. They lead the industry in R&D by a considerable amount so that they can make sure the products they create and offer are the easiest to install. A product that is easier to install means plumbers can take on more jobs, with less stress, and less risk of failure. The firm even invites plumbers to participate in free training for new products in order to ensure product familiarity. If necessary, Geberit will send members of their own sales force to a job site to help with any issues. Each individual feature of the company’s service level represents an investment in a plumber’s success, trading off additional cost to win loyalty. Each successive conscious choice by Geberit represents a taller hurdle that less capable competitors must climb to win business.

A skeptic would simply say that fulfilling a customer’s need is the base reason of existence for any company. They would be correct, but only to a degree in my opinion. Yes, firms exist to fill a market need. But competing on the basis of minimum viable standards invites price wars or fighting harder just to stay relevant because any action is easily imitated. Rather, differentiation is the key to any value proposition and people will pay, even extra, for true value whether that is something of superior quality or something that makes their life easier. But getting to that point involves an ethos and grander strategy of intentionality that is costly and built upon decision by decision.

Sherwin-Williams is a further example. For any paint job, 80%-90% of the job costs come from labor, not from paint itself. Thus, for a contractor, more time on one project means the next job (and paycheck) is pushed out further into the future. This is where Sherwin-William’s superior distribution network provides value. The company has well over 4,700 stores across the U.S. while rival PPG has just over 1,000. Odds are then that for a contractor his current and next job is closer to a Sherwin-Williams store than any other. Duplicating this extensive distribution footprint for any competitor would be an enormous undertaking in managing a supply chain as well as extremely costly.

Not to mention the investment the company puts inside each store. The company spends more than competitors on R&D in order to launch 20-40 new products each year that comply with evolving trends in building materials, improve reliability, enhance quality, or be applied in an easier fashion. All this means less time on the job and thus the opportunity to do more jobs for a contractor. There’s a reason 23 of the top 25 homebuilders in the U.S. exclusively use Sherwin-Williams products. Not to mention, that all managers must undergo a 4 year training program in order to work for the firm before managing a store. Here they must become experts on everything from their large product catalogue, sales tactics, changes in industry trends and more. The company pays salaries a considerably higher than average salary (reducing turnover), incentivizing better service to contractors. Better service breeds loyalty to the next job. Higher R&D. A larger distribution footprint. Higher salaries. All align with the goal of making the job for contractors easier to do by differentiating from competitors, even if that means added costs for themselves. The payoff for Sherwin-Williams is a business with ROIC 300bps greater than their (worthy) chief competition and superior returns for investors.

Figure 2: Sherwin Williams’

A painter doesn’t want to spend his workday in his vehicle going to pick up supplies; that’s not where his own differentiation or value-add lies. Similarly, an ecommerce store doesn’t want to have worry about building payments infrastructure into their website manually; it’s far outside their area of competence and soaks up resources that could be better spent building a business that stands out from other retailers. And there’s not many industries more complex or antiquated than payments. It’s why Stripe set out to simplify taking payments online, a problem that still befuddles many. A store can simply copy Stripe’s own source code into their own website and within a few minutes they’re set up to take payments online. All the complexity gets abstracted away, hidden in the background for someone else to deal with, saving time and stress.

Similarly, an e-commerce company wants to focus on selling goods and services, not having to worry about building a website, cybersecurity, creating promotional codes, making shipping labels, international shipping rates, currency conversion, and more. All are necessary but ancillary to the core goal or objective of the business. A company that can abstract those “chores” away would be enormously valuable to you, which is why Shopify has been so successful, especially if they let you maintain relationships with your customers and will not compete with you, unlike Amazon.

TSMC, chronicled a bit earlier this year, functions similarly; they work in concert with dozens of companies in the ecosystem to consult on designs years in advance, recommend new methods, and develop IP.

The example of these businesses above all demonstrates the value proposition of reducing frictions. They make their partners more successful and productive, freeing up resources so that they can concentrate on the tasks that actually account for profitability. Their relationships with customers and partners is not exclusively transactional in nature. They have mutually beneficial interests and see each other’s success as paying dividends for themselves at some point, not in an altruistic sense but rather in an attempt to grow together instead of at each other’s expense.

Building up this type of business is beyond complicated and may even be more costly than necessary; but when effective they generate the type of positive-sum outcomes that are durable and keep customers coming back and investors happy.