We’ve demonstrated that companies that generate high ROIC are time and again the most valuable businesses and stocks to own. In addition, the persistent presence of excess returns points to a moat, a unique business model, inimitable set of characteristics or assets, or other source of competitive advantage that allows for them to generate stronger returns compared to peers. As a result, these companies deserve valuation ratios that cursory levels of analysis frequently deem excessive or expensive. In short, not all businesses are equal and should be subject to a blunt, one-size-fits-all method of valuation. But going further, the corollary that flows from our last examination into high ROIC businesses is that they themselves are not all created equal.

Specifically, a business with abnormally high economics can only continue outperforming a basket of stocks if it is able to reinvest its earnings/cash flow back into the business at incremental returns that capture high returns. If a businesses with excellent levels of returns is out of reinvestment opportunities, the stock will essentially be an average performer. Said a different way, ROIC generated today reflects investments and strategy employed in the past. Investing, however, is an exercise in capturing the future and compounding value into the future requires both high levels of returns and incremental opportunities for reinvestment/value capture. The uncertainty of sustainability and predictability of future cash flows, reinvestments and return levels is what makes the investing game inherently difficult.

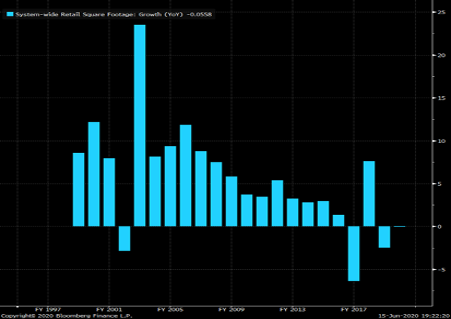

Take Walmart as an example. By the time the store had 50 locations it was generating astounding pre-tax returns of over 50% in the early 1970s. Its scale economics gave it a cost advantage over mom-and-pop retailers that it passed on to customers, attracting greater levels of foot traffic. More customers meant greater leverage on its costs and gave the company greater purchasing power from merchants. Greater purchasing power meant cheaper goods, starting the cycle over again. The model and customer value proposition was clear. Opening up additional stores would only compound its already sizeable advantage over competitors year after year. Eventually, however, its stores reached the point of saturation (i.e. the runway for reinvestment had largely dried up) and the rate at which new stores were cannibalizing sales from old stores was growing. The number of new stores and total square footage both stagnated in the early 2000s and slowed considerably after the Financial Crisis.

Figure 1: Walmart New Store Growth and Total Square Footage

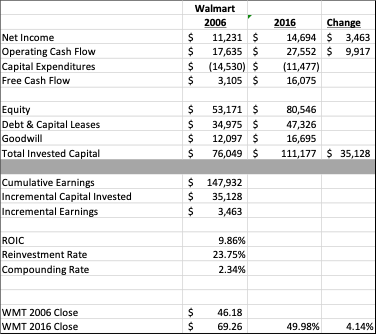

The financials bear this out. Between 2006 and 2016 Walmart grew its Net Income by almost $3.5 billion. The total amount of tangible capital invested in the business increased by roughly $35 billion for a return of roughly 10%, a very mediocre amount and generally in line with the average stock in the market (Figure 2). The fact that Walmart compounded its intrinsic value at a mediocre 2% for 10 years explains the vast majority of its underperformance in the stock market during the time period.

Figure 2: Walmart’s Return on Invested Capital and Stock Returns (without Dividends)

Similarly, both the returns and amount of capital invested are crucially important to compounding intrinsic value. For instance, imagine a firm that can invest $100,000 at 50% returns vs one that can invest $10,000,000 at 20% returns. The former is able to add $50,000 of value to the enterprise, but the latter, despite the “inferior” return profile of its investments, adds $2,000,000 of value to the corporation. It’s this reason why a company like Procter & Gamble has essentially been an average stock for the last ~15 years despite core economics that are quite favorable. Unlike Walmart, its incremental returns are strong; it generated an additional $590M in Net Income in 2018 on additional capital of about $3.5B (an ROIC of ~17%). But on an Enterprise Value of over $200B such returns don’t move the needle. Combined with the competitive headwinds facing many brands the market is pricing in (as we detailed here), it looks set to continue its mediocre performance despite some core value still in place in the business. Expecting outperformance from a stock because it’s possible to calculate a favorable level of ROIC isn’t enough. To capitalize on its favorable traits, it has to be able to exploit and expand its value proposition.

A counterexample, over the same time period that Walmart was discussed, would be Chipotle. Per Saber Capital Management, a single restaurant generates net cash returns of over 25%. By expanding its footprint, it was able to multiply its prior strengths and increase its intrinsic value per year by 20%.

Figure 3: Chipotle Return on Invested Capital (Source: John Huber, Saber Capital Management)

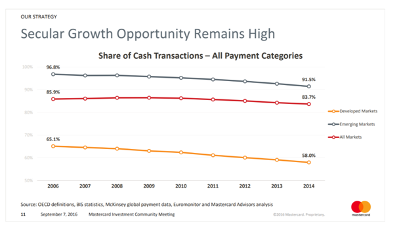

A further example is the two most powerful payment networks in the world: Visa and Mastercard. For decades these companies invested billions after billions to interconnect every permutation of bank and customer, regardless of geographic border. As consumer activity on a global basis continues to make up a greater portion of GDP, odds are more and more payments flow through their networks of merchants and card issuers. Most importantly, the runway to capture this volume was enormous. Cash as a proportion of global purchasing transactions exceeded 60% around the time of the financial crisis and still makes up around 40% of global volume today (Figure 4).

Figure 4: (The Runway of Digital Payments)

The networks’ share performance since then is exactly reflective of both their tremendous ROIC (it costs a fortune to process one transaction…but hardly anything to process the marginal one) and their runway to capture the opportunity.

Figure 5: Mastercard and Visa vs the S&P 500

In our last series of comments regarding ROIC we said the merits of value investing are meaningless without an examination of a business’ returns. The corollary would state that the merits of investing in a company posting high levels of ROIC only exist if growth is available. Taking advantage of true, long-term compounding requires careful consideration of the true drivers of a firm’s ROIC, whether those forces are sustainable or not (Chipotle vs Walmart) and whether there is adequate runway to capture prior deposits of value creation (P&G vs Mastercard/Visa).