With financial reform just passed by the Senate, we wanted to take the time to express our delights and concerns of the bill while paying special recognition to Mr. Paul Volcker, a mind and figure unlike any other in modern financial history. The unfortunate thing, is that the Chairman is not recognized and appreciated as much as he deserves, especially when we take into account that he stepped in and saved our country from disaster a few times. What I admire in the Chairman, is his “truth to power” mentality that has made him a revered economist, financial expert, the best ever Chairman of the Fed, and the most important man in the U.S., according to Congressional testimonies.

Having worked for the Federal Reserve System for over 50 years, Mr. Volcker’s popularity and esteemed reputation peaked as a result of his competence during the fragile decade of the 1980s. Appointed as Chairman of the Fed by President Carter in 1979, Mr. Volcker was charged with reviving an economy that was both stagnant and inflated at the same time. Yet the enormity of the challenge in front of him didn’t faze the Chairman from making tough decisions. Raising interest rates to over 20%, Mr. Volcker successfully lowered inflation from 14% in 1979 to just over 3% in 1983. However the Chairman’s work was not done in 1983.

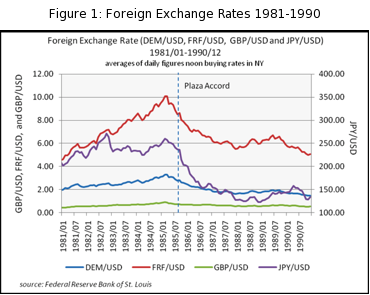

The Fed’s policies on interest rates had drastically raised the value of the dollar relative to other currencies, stifling trade. Faced with volatile currency markets and a rising current account deficit, Mr. Volcker orchestrated international collaboration on restoring stability in global markets by gradually depreciating the dollar through direct intervention with the Plaza Accord of 1985. By the time his tenure as Chairman of the Fed ended in 1987 Mr. Volcker was a titan of financial markets, commanding their movements like a conductor of an orchestra and harnessing their trust. Congressmen of the 1980s describe him as the best politician of the decade, able to persuade and wield the players in D.C. thanks to his towering presence (he stands 6 ft 8 inches) and stern demeanor, just as well as the financial markets and central bankers. It’s the giants of the world that pioneer society and transcend history, and Mr. Volcker is undoubtedly the ultimate giant of the confidence game.

As is the case with giants, Mr. Volcker was not beloved by all. He’s joked that he’ll enter a coffee shop and be greeted by someone with high praise and gratitude because the high returns on Treasury bills helped pay for his child’s college education, whereas upon leaving he would be blamed for making credit more expensive for businesses. More relevant is his history of concern over the rapid deregulation of financial markets that began while he was in the highest of circles in the 1970s, which led to his departure from the Federal Reserve . In fact, Mr. Volcker has stated that one of his largest regrets was not speaking out more forcefully on the shadowy activity of the banking industry over the past 30 years.

Yet with the tragedy and destruction wrought by the financial crisis, Mr. Volcker’s services have been tapped again. As the Chairman of President Obama’s Economic Recovery Advisory Board, Mr. Volcker and his fellow board members are charged with advising the President about the issues at stake, but his greatest contribution has been the implementation of the Volcker Rule. In its initial form it was designed to ban proprietary trading, separating commercial banking from involvement in volatile, opaque, and risky/toxic instruments, such as collateral default swaps. A recent New York Times article quotes Mr. Volcker as being distraught at how deeply entrenched speculative trading had become in the U.S. Financial System. Thanks to a full-court press of lobbying efforts by the giants of Wall St, the reform bill and the Volcker rule have been diluted, but still something is better than nothing.

My reading is that Mr. Volcker would have given the current bill a grade of a B, voicing concern over the long-term prospects of financial regulation as private equity firms, hedge funds, and proprietary trading will not be restrained to the degree the Chairman hoped. Once again, politics got in the way of prudence on Capitol Hill. Most disconcerting to Mr. Volcker seems to be the mentality and philosophy regarding financial regulation, that has not matured in the wake of this crisis. Unbridled financial creativity put the brakes on global economic growth and yet the spirit of institutions like Glass-Steagall, the law that separated commercial and investment banking, is still difficult to resurrect.

But the shortfalls of the financial reform bill should not come as a surprise when examining the timeline of the reform process. Mr. Volcker’s speeches and presentations across the country for over a year, have emphasized the necessity of corralling who can engage in the trading of convoluted assets and to what degree. The Chairman also stood on the side of breaking up the biggest banks and to separate their operations, so as to prevent recklessness of sinking the real economy. His op-ed in the New York Times in January of this year articulates some of his views and priorities, as well as his urging of structural reforms.

Throughout the life of the financial reform debate Mr. Volcker has been pushing for the same points over and over, which means one thing: someone hasn’t listened. Given the background of current administration officials such as Mr. Summers, and Mr. Geithner, it’s no surprise that the structural reforms called upon by Mr. Volcker have been moderated at best and may even be ignored at worst, so as to allow the powers that be to escape the reform process without being put in their place in the stern fashion they deserve.

Mr. Volcker still remains optimistic about the bill, saying that its ultimate success depends upon the urgency and prudence with which it is implemented. But don’t be surprised if within a decade we look back and ask what the bill really accomplished, says the Chairman. It’s too bad we have to leave the bill in the hands of hope as opposed to confidence, especially with a titan of experience and judgment at Washington’s disposal.

With a humble heart, kudos Mr. Chairman for all you have been doing in order to make the US a better place.