Turkey has become a critical pole in the future hierarchy of global political and economic influence. The recent turmoil in the Middle East seems to be a prime opportunity for the role it wishes to play in the global politico-economic landscape. Over the past few years it has accumulated credibility and built networks of relationships from South America, to the Arab world, to Central Asia. It has a variety of components and identities with which it can use to relate to a number of parties. In the era of power diffusion, Turkey’s geostrategic significance and versatility as an actor grants her a special form of influence in a turbulent region.

Foreseeing that Turkey would be in such a position in 2011 would have been unimaginable just ten years ago. Dealing with a vast array of economic woes following a collapse, ethnic tensions at home, and a lesser role compared to other regional actors, Turkey didn’t have the prospects that it has today. While still troubled with a number of these factors (Kurdish relations, unemployment at home, a persistent current account deficit, and East/West development divides, among others) Turkey is poised to be a premium example of emerging countries commanding greater portions of the economic and political pie, thanks to its political leadership, economic modernization, and expanded international presence.

Political Influence

Thanks to its geographic location, cultural ties, and flexible identities Turkey has become a global player in world affairs. Last summer, on the eve of new UN sanctions targeting Iran’s nuclear facilities, it was Turkey (along with the other developing rising star Brazil) trying to secure a nuclear swap arrangement so that sanctions would not be needed. Turkey was seen stepping up to the plate of global governance and agendas as opposed to regional configurations and issues. Yet, Turkey’s greatest leverage is still most potent in the regions of Europe and the Middle East, the latter of which Turkey has provided greater attention to in recent years.

When the government in Lebanon collapsed last month, Turkey (along with Qatar) had delegations in Beirut within an instant, attempting to broker a compromise on a new government. The complexity and various sects at work in Lebanon’s political structures demanded resources familiar with working outside traditional boundaries. Turkey was a vital cog in the wheel of NATO’s forward outlook at the Lisbon Summit in November. Turkey also possesses influential roles in Iraq and Afghanistan as both countries trying to get out of disastrous situations. Turkey still performs its song and dance with the EU when discussing membership prospects. And most recently Prime Minister Recep Erdogan warned President Mubarak of Egypt to “step down” and “take steps that will satisfy his people.”

Turkey’s ascendancy is one example of the new age in global politics and international affairs. Global influence is more dispersed than ever before. The era of globalization allowed capital and ideas to reach places in an amount of time that the world has never before seen. To those who were able to grab on, the opportunities presented by the convergence of capital (both physical and human) allowed for an elevation of status and gradual sophistication of schemes, goods, and services. It seems that the connectivity of the world has put a premium on contextual analysis in order to move up the value ladder with maximum efficiency. Little corners of the world could now be a source of global significance. In this day and age, a simple online messaging service (Twitter) could be the source of intelligence unavailable by other means (Iran in 2009) or organize massive, nationwide protests that rock a regime of 30 years (Egypt). Al-Qaeda, an organization of 500-1000 operatives at the time of 9/11, had the effect of changing Washington’s global priorities.

Thus, an added source of leverage and influence in international affairs today is the ability to relate to these contextual narratives that can have global ramifications. Turkey’s flexibility and its ability to fit with various identities provide it with access to a wide range of networks. Like much of the Middle East it is a Muslim country. Yet it combines its religious fervor with secular institutions and democratic traditions. As mentioned earlier, it is a member of NATO, an alliance that affiliates Turkey with the West. Its largest trade partners are Europe and the U.S. It knows what it’s like to depend on IMF credit lines to stay afloat. It has problems with terrorism. And finally it knows what it’s like to deal with poverty.

Economic Influence

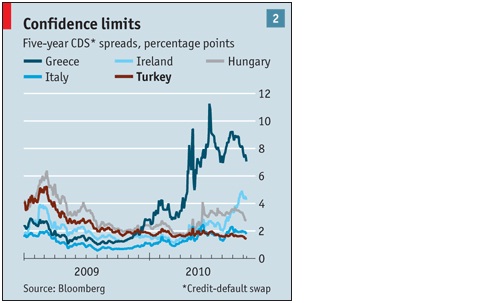

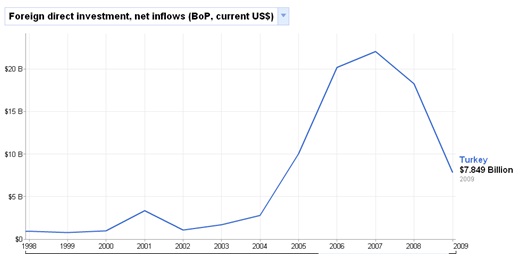

Turkey’s political and diplomatic reach (recently inducted as a member of the Arab League) is but one part of its increased global activity. The past two years alone have seen Turkey record its greatest increase in trade volume over any two year period. As Figure 1 demonstrates, FDI flows into Turkey exploded until the financial crisis, which contracted Turkey’s economy by nearly 5% in 2009 (see Figure 2). Yet despite Europe’s continued troubles (the main source of FDI inflows) Turkey managed to recover her growth in 2010, expanding by over 7% and now claiming the title as the Middle East’s fastest growing economy. While growth in 2011 probably may not hit such a high mark, it is still expected to be robust.

Figure 1: FDI Inflows into Turkey

Source: IMF, World Bank Statistics

Figure2:TurkishGDPGrowth

Source: IMF, World Bank Statistics

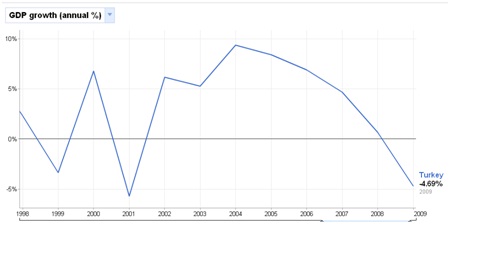

Looking forward, Turkey’s development path only looks brighter. It has expanded the size of its manufacturing sector with great success in industries such as cement. It has a young, educated population that will be able to stream into the expanding service sector and possibly rejuvenate an aging Europe and send back remittances. Turkey is poised to be an energy corridor in the future as Europe looks to diversify from Russian energy sources, bringing further investment and contacts to the country. Turkey has also signed contracts with Russia to construct nuclear reactors, a traditional symbol of political stature. It is also about to get an investment grade sovereign bond rating as markets already trust her more than some members of the EU (see Figure 3). After a financial meltdown in 2001, Turkey has recapitalized her banks and substantially reduced its public debt. Inflation, once at 75%, has come all the way down to under 6%. We wouldn’t be surprised if Turkey’s capital markets continue reporting significant gains.

Figure 3: CDS Spreads