We’ve mentioned on several occasions in previous newsletters and commentaries our positive growth outlook for numerous emerging economies in the near future and the growing interconnectedness among them. This isn’t the first time that developing players command an increasing proportion of global economic and political activity: the Silk Road connecting China to the Middle East and Europe is the most conventionally known title for interconnectedness.

Part of the year-end analysis that we perform is to identify hotspots around the globe and examine how developments there could influence growth in the region and potentially create tremors in interconnected markets. In a series of commentaries we inaugurate now, we will be visiting those hotspots and their implications for the global markets. Given the developing Silk Road it seems fitting that we begin our series of examining the current and future crosshairs of global politics and economics in Central Asia. We will start with the events circulating Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan typically don’t make the headlines with positive news; both are in the middle of a region wrought with terrorism and violent sectarian clashes. While posting high growth in the mid-2000s, the structure of Kyrgyzstan’s growth is nothing to get excited about; however, the currents of globalization’s tide and the rise of new poles of power gather momentum for paying attention to the roles of new actors and issues. Central Asia is such a region as nearby giants such as China and India diversify their sources of inputs, feed their growth machines, and project their influence further out so as to protect their interests. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan will not have the dynamic roles in the region that say Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan will, but they still serve as examples of a fast-approaching era where new powers are sitting closer to the head of the table when it comes to framing global structures.

As was briefly mentioned, analyzing Kyrgyzstan’s economy in and of itself doesn’t offer much of a significance. The country depends heavily on the economic opportunities in surrounding countries, particularly Russia, as remittances account for 40% of GDP. The Kumtor gold mine, Kyrgyzstan’s most significant economic asset, alone accounts for 25% of industrial output and over 30% of the country’s exports. Such dependence is never a good model for economic growth. Agriculture still takes up a large portion of the labor sector, a common proxy for underdevelopment. Unlike some of its neighbors, Kyrgyzstan isn’t endowed with the gas and oil assets of Turkmenistan or Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan’s ethnic rival, whom it relies upon for importing energy with frequent episodes of tension and cost frictions.

More distressing than Kyrgyzstan’s current economic makeup is its political hurdles. Corruption, incompetence and malfeasance are systemic; bribes and political favor make the economy, and the country as a whole, run. Blackouts, high energy prices, unemployment, security shortfalls and narcotics have plagued Kyrgyzstan for quite some time and 2010 demonstrated the potential instability these elements can bring.

Compounded upon each other, these factors propelled opposition movements to oust President Bakiyev in April 2010. It didn’t hurt that the opposition movements, having lost faith in the 2005 Tulip Revolution, were supplemented with the extensive reach of Russia’s control of Kyrgyzstan’s media. The transition for Kyrgyzstan however was plagued with ethnic rivalry and violence, something found frequently in Central Asia. The southern part of the country saw mounting violence and casualties between minority Uzbeks and Kyrgyz, forcing the interim government into declaring a state of emergency. By the time the dust had settled in Kyrgyzstan the world could see that the country lacked the institutional and structural framework to keep its economic engine humming for an extended period of time.

Still, in spite of its dilapidated institutions and fragile foundations, Kyrgyzstan will only receive further attention and greater opportunities to break through in the coming future. For one, Kyrgyzstan offers geographic value thanks to the Fergana Valley. Thus, basing rights and security relationships (which also put Kyrgyzstan in the news in the recent past) will continue to be a featured focus going forward especially given America’s presence in Afghanistan, Russia’s geopolitical complex and an expansive China. Second, Kyrgyzstan should also see increased attention and capital flows due to greater awareness of the supply of rare earth elements (REE). Fears of dependence and shortages have prompted countries like South Korea and Japan to pursue exploratory mining contracts within Kyrgyzstan for the batch of elements. Should initial prospecting turn promising, additional deals and actors could enter the picture.

Tajikistan

If the situation gripping Kyrgyzstan seems bleak and sour it should take comfort in one thing: it isn’t Tajikistan. Tajikistan, for quite some time, has been the only Central Asian republic poorer than Kyrgyzstan. Like its neighbor to the north Tajikistan is heavily dependent on employment opportunities outside of its own borders. Remittances amount to 50% of Tajikistan’s GDP according to the International Organization for Migration. Income inequality hasn’t improved since it gained independence with the fall of the Soviet Union, thanks in part to civil war of the mid-1990s.

Over half the Tajik population lives below the poverty line. Aside from Kazakhstan, the Central Asian republics have struggled to attract FDI. Drugs and other illicit forms of trade are significant sources of income for the Tajik population but often bring with them violent forms of competition for markets and resources. While Tajikistan is a strong exporter of aluminum and cotton, volatile prices make planning and investment difficult.

Politically, Tajikistan’s situation is even more grim. U.S. officials, particularly security officials, fear that Tajikistan will become the preferred haven for terrorist activity in Central Asia in the not too distant future. The Tajik minority in Afghanistan is already an active component of the insurgency against the U.S. Porous borders have allowed for crime and drug networks to expand outside of Tajikistan’s own territory into other parts of the region and allowed clans associated in such systems to garner more power. Corruption is pervasive, serving as the most secure line of employment for many in the country. Political competition is virtually nonexistent; economic competition is also rare due to government interference. Even when foreign direct investment is secured, it’s usually to benefit areas in which government officials have a stake.

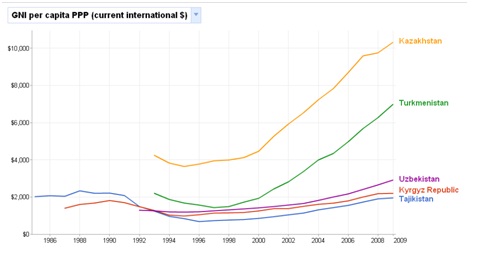

The figures below portray the poor state of both countries relative to their poor neighbors Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan.

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators

To make a case of optimism on behalf of Tajikistan, its recent developments in domestic energy offer some hope. Much like Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan has been dependent, and often hostage, to Uzbekistan for gas supplies and has often been a victim to the latter’s compulsions for power plays. Recently however, Tajikistan has started drilling its Sarikamysh field containing approximately 60 billion cubic meters worth of gas according to Radio Free Europe. At a global level, such amounts are meaningless. For Tajikistan however, such a sum is enough to keep them energy independent for 50 years, saving the impoverished republic significant funds and avoids wrangling with Uzbekistan.

A related benefit from the Sarikamysh field is the development of hydro power capabilities. Prior to the gas find, Tajikistan dedicated itself towards creating industries to wean off its independence from Uzbekistan. With the discovery of gas, some analysts believe this could free up Tajikistan’s hydro power resources to export electricity. Moreover, the State Department notes the potential for Tajikistan’s hydro power sector to be a significant resource in the region’s irrigation schemes.

Looking Ahead

In his highly acclaimed and award-laden book, The Bottom Billion, Paul Collier demonstrated, theoretically and empirically, that economic growth in one country could spill over into a neighboring, landlocked country, increasing the latter’s GDP by 0.2% per year. Given that Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are the poorest countries in Central Asia, developments in the region as a whole will only become a more critical component of these two countries growth prospects.

Given that remittances make up an enormous amount in both countries Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan will be at the mercy of their neighbors: China, India, Russia, as well as Kazakhstan to a lesser degree. Both countries would be wise to dedicate their resources to making their domestic populations employable and competent, securing their own borders and cracking down on drugs and crime so as to attract foreign direct investment. For the foreseeable future, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan will go as far as the major actors around them can carry.

We only hope that this will not be the case with the 54th sovereign African State (South Sudan) whose birth is anticipated soon.

Ode to independent, self-determined, and competent states!