Market bifurcation, as discussed in the previous commentary, is not an exclusive right of markets and geopolitical philosophy/practices. Ten days ago, OpenAI (the parent company of ChatGPT) demanded that right too, after first firing Sam Altman (one of the founders) and then, 24 hours later, contemplating bringing him back, possibly affirming the closing paragraph of that commentary.

The contemporary evolution of post-modernity can possibly be summed up with two words: magnificent ruin. The question is what do we do with that? I prefer to start by borrowing the words Octavius Ceasar used to characterize his main rival Mark Antony as an “abstract” of our faults (for references about market trajectory as a reflection to their rivalry see here and here). The Greek poet Cavafy in his poem “The God Abandons Anthony” will sum it up well too:

“…don’t mourn your luck that’s failing now, work gone wrong,

your plans all proving deceptive -don’t mourn them uselessly …

…say goodbye to her, to the Alexandria you are losing.”

Where does that market bifurcation stand now? The first two figures below tell us a story of soft landing as excess savings (that can continue financing spending) remain relatively healthy. In addition to that, the second figure enhances such perception showing that liquid corporate assets not only remain healthy, but also that the net interest payment by corporations (after inflation is deducted) is pretty low, which, in turn, can finance investment. Could there be any hubris in such a perception?

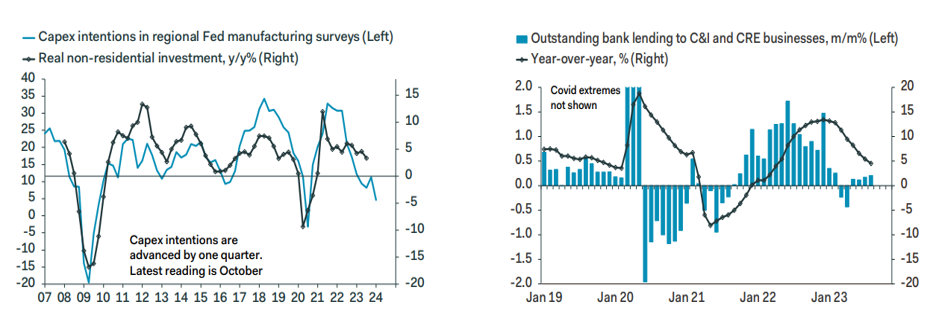

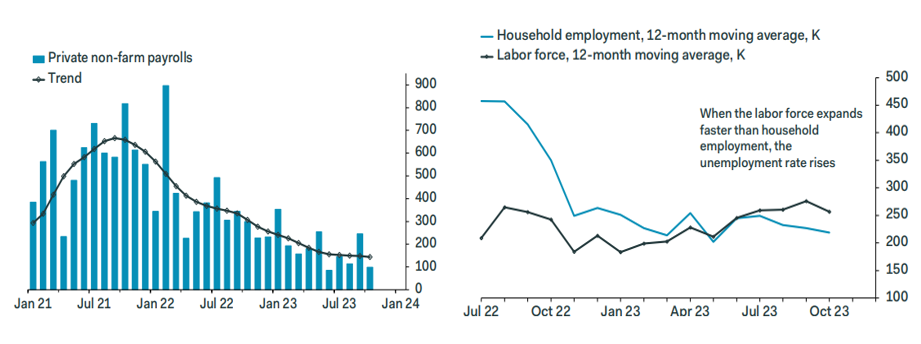

The following two figures point to the possibility of a different projected reality: The first figure tells a story of declining investments which, when combined with the tightening credit standards of the second figure, could narrate a story of a forthcoming recession. If on top of that, we consider the next two of declining payrolls in the midst of a rising labor force, then the signals of a recession become stronger.

The Nietzschean tragedy of the will to power – as described in our previous commentary – was inspired by Nietzsche’s myopia to overturn the Socratic philosophy of virtue and replace it with a Dionysian license of chaos. So then, the question becomes who is that god – as Cavafy described above – who is abandoning Mark Anthony? None other than Bacchus (Dionysus), the beloved god-myth of Nietzsche. Bacchus abandons Mark Anthony given his undisciplined intrigue with Cleopatra.

The Nietzschean tragedy is none other than the consequences of the will to power (from Lenin and Stalin to Hitler and the atrocities committed nowadays by the likes of Putin, as well the innocent victims’ blood in Israel and Gaza) witnessed by world history.

The defeat of Mark Anthony enhanced the notion that the era of the Roman Republic was over and that the era of the Roman Empire was upon the world. That Day After necessarily came as an opaque and bifurcated reality. There is a mystical element in the realm of any empire: In the first phase, noble patriotism along with human agency, objective intervention, and accountability are weakened. In the second phase, it becomes hubris. This is our human story since the Garden of Eden.

It has been the argument of our commentaries for some time now (hence the Day After that we are using) that an uncharted passage from a republic to an empire – which America might be on – implies an identity crisis. Reinhold Niebuhr called that passage “a vast web of history, in which other wills, running in oblique or contrasting directions to our own, inevitably hinder or contradict what we most fervently desire.”

The Persians by Aeschylus is the oldest drama in the Western tradition. It was drafted around 472 BC and is about the Second Persian War led by the incompetent Xerxes. Aeschylus, who fought at the battle of Marathon, doesn’t simply present history as a drama-play. He is sending a forewarning to his fellow Greeks and to all the empires that follow about hubris and the will to power. But let’s do a quick historical review:

The Persian Empire was established by Cyrus the Great around 550 BC by defeating the Median Empire and then absorbing Lydia and Greek cities in Asia Minor. Simultaneously, it expanded eastward to the borders of India. Cyrus was succeeded by Cambyses and Darius, both of whom strengthened the image of an invincible empire. The hard reality of non-invincibility dawned on Darius at the defeat his forces experienced in the battle of Marathon in 490 BC. Four years later and upon his death in 486 BC, he was succeeded by his incompetent son Xerxes when he demonstrated hubris on his journey called “the will to power.”

Xerxes never comprehended that it was already the Day After when he started planning for the second invasion of Greece. Father and son were obsessed with conquering Greece. Almost 2,500 years later, another son will try to imitate his father and invade Iraq. The rest of that tragedy is well-known to our generation as we still pay the price.

Aeschylus depicts Darius as a successful leader succeeded by his incompetent and hothead son Xerxes who, in 480 BC, invaded Greece only to be humiliated in Salamis. Aeschylus will write of that humiliation where the pile of corpses kept rising along the shores of Salamis, “till every living man was butchered.”

As we stated earlier, Aeschylus’s drama-play was not just about the Persians. As any good tragedian, he was sending a forewarning to the Greeks and other future empires about their will to power ambitions. The Sicilian expedition ended up costing the Greeks dearly. Not only were they humiliated, but the expedition ended up weakening them to the point of losing to Sparta in the Peloponnesian War. That expedition started with a small dispatch of about 20 ships which grew to over 100 triremes accompanied by 40,000 Athenian troops. Someone may draw parallels between President Kennedy’s expedition to Vietnam which also started as a small dispatch of advisors and limited operations, and later, under President Johnson, grew to over 500,000 soldiers. Somewhere behind the curtains, there is an accountant who keeps records of that “pruning shear of arrogance” as Aeschylus stated. The Frank Church Committee will write history in the mid-1970s, and he will be called the Last Honest Man in the book by the same title authored by James Risen and published a few months ago.

Coriolanus is one of the last two tragedies authored by Shakespeare, the other one being Anthony and Cleopatra, which also fits the message of this commentary. It’s based on the story of a decorated General who is feared by both friends and enemies, but who has no limitations on his own journey, also named the will to power. In the midst of Coriolanus’s hubris, the plebeians object to him becoming a Roman Consul. Coriolanus is enraged and loses his capacity to reason to the point of aligning with Rome’s enemies and leading an insurrection and an invasion against his own capital Rome! Hubris was at its glorious point, when reason and a bifurcated state of mind leans towards lunacy, only for catharsis to come when the enemies of Rome ended up killing Coriolanus after he brokered a peace agreement between them and the Romans. Obviously, that great General (Caius Marcius Coriolanus) had forgotten Aeschylus’ warnings.

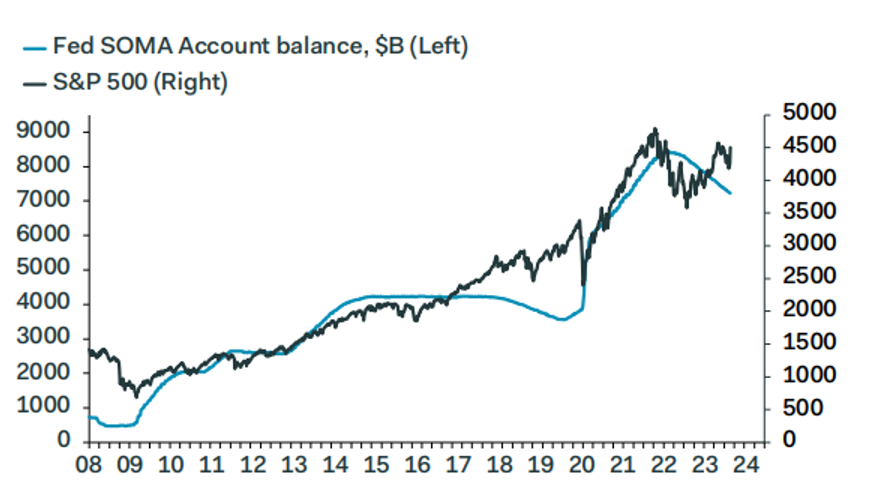

So what does all of this tell us about the equity market trajectory? The figure below may point to a break in the relationship between the Fed’s balance sheet and the trajectory of the equity market, as it shows an upward trend for the S&P 500 at a time when the balance sheet of the Fed shrinks. Is such a break sustainable?

Before we close, we need a few more words about that Aeschylean accountant, mentioned above, who keeps records of that “pruning shear of arrogance.” But then I thought, what better way to close this commentary than to describe that accountant with an echo from the island of Patmos in Johnny Cash’s song titled “The Man Comes Around”?

“And I heard a voice in the midst of the four beasts

And I looked and behold a pale horse

And his name that sat on him was death, and hell followed with him.”