Bob Farrell’s 10 Market Rules for Investing is a timeless list of wisdom which immortalized the strategist. After studying under Benjamin Graham and David Dodd at Columbia, Farrell worked at Merrill Lynch for 45 years and eventually became their Chief Market Strategist in the 1970s. Institutional Investor recognized him as a member of their Hall of Fame due to the strength of his track record. While initially a fundamental analyst, Farrell evolved to incorporate technical analysis in his market calls.

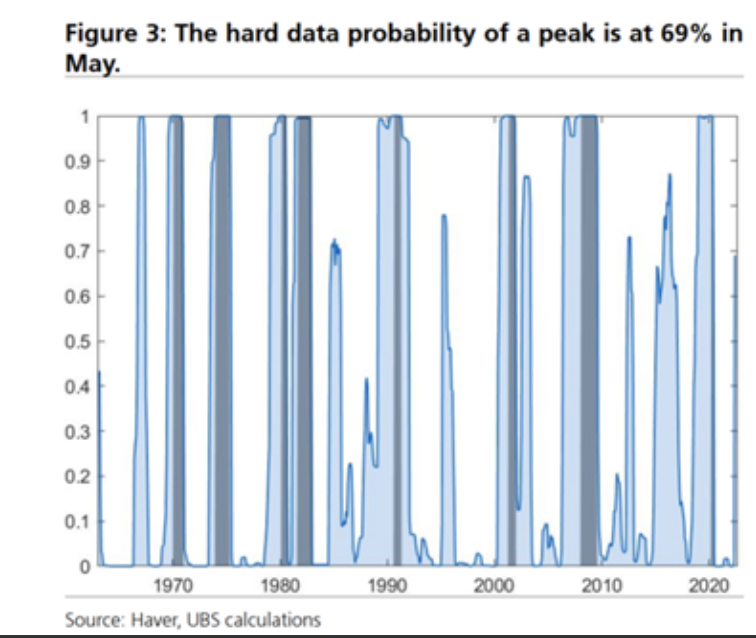

Farrell’s rules always make for a good read and his second rule seems especially relevant as the major indices have posted one of the worst first halves of the year in their history: “Excesses in one direction will lead to an opposite excess in the other direction.”In speaking with other investors across the country, reading financial commentary, and Wall Street analysis there is currently a strange dichotomy. First, there is an obsession about if/when a recession will grip the U.S. economy. The commentary is endless. Take UBS’ hard data model, updated yesterday, which gives the probability of a recession within the next 4-20 months at 69%.

Figure 1: Hard Data Model Puts Probability of Recession at 69%, Source: UBS

Second, within the investment community, there is a constant asking of “Is it priced in yet?” “Have we reached the bottom?” These latter questions certainly suggest that the despair, grief, and hopelessness frequently seen at market bottoms is not there yet. It may exist in certain pockets of financial markets (crypto, unprofitable and unproven technology, SPACs, etc.) but the market as a whole seems to be gleaning optimism and hope.

It also flies in the face of Farrell’s second rule, even with the pain seen in markets already. Despite the S&P reaching bear market status the index currently trades at 17x projected earnings for 2022.

Figure 2: The 500 Now Stands at 17x Estimated 2022 EPS

17x is certainly more in line with what some consider a fair multiple to pay for a quality basket of companies. But markets built up on excess don’t end at “fair” value. They see excesses on the other side. And that’s before we even address the ‘E’ in the market’s P/E ratio.

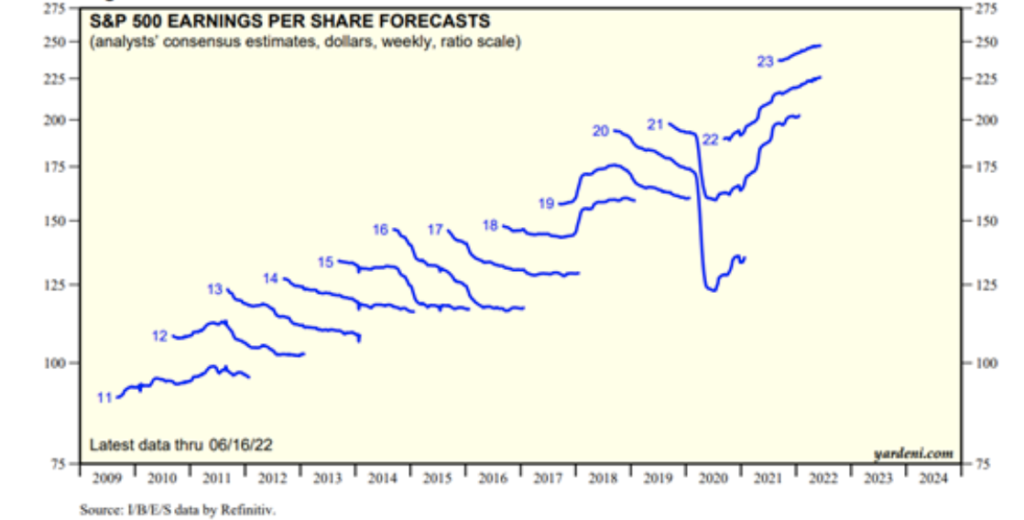

The normal trajectory for Earnings Estimates is to start out high and move down throughout the calendar year (Figure 3). There are exceptions – coming out of a deep recession in 2011, corporate tax cuts in 2018, and the 2020/2021 period thanks to enormous fiscal efforts – but otherwise the trend is quite reliable. And yet earnings estimates have done nothing but go up for 2022. In fact, analysts haven’t been this bullish in their estimates for corporate earnings in the last 20 years. Unless there is some sort of positive exogenous shock around the corner then these numbers need to move down.

Figure 3: EPS Estimates Haven’t Budged, Source: Yardeni

Figure 4: Analysts Haven’t Been This Bullish in 20 Years

The question then is what multiple is the current index really trading at in the event of a recession? Even if earnings come in equivalent to 2021 (i.e., no contraction), that 17x multiple rises to nearly 20x. The historical precedent of buying a basket of stocks at 20x earnings is not very good. And that’s just with flat earnings. In the event of a contraction in GDP earnings will decline year over year (Figure 3).

Figure 5: S&P 500 (White) and Earnings (Orange) During A Recession (Red Bars)

We’ve had contractions in earnings without a contraction in GDP (2015-2016), but the inverse doesn’t happen. It’s pretty easy to see that the cursory look at the S&P 500 seeming optically “fair” in price quickly becomes expensive. And that’s long before we incorporate Farrell’s rule regarding excesses on the downside.

Go back and examine Figure 1. In the prior bear markets in the last 30 years, both containing excesses (technology and credit respectively) the market did not stop going down at fair value. It got downright cheap: ~14x post the tech bubble and below 12x in the aftermath of the GFC. If you combine the possibility of excesses on the downside with moderate earnings declines and it’s not difficult in the slightest to see more than 30% downside in the S&P 500 from current levels.

Does it have to happen? Of course not. And there are some reasonable counterarguments against the above:

- Just because markets haven’t stopped going down at fair value in the past doesn’t mean they can’t in the future (i.e. this time is different). Moreover, the market is much cheaper on a FCF basis than an earnings basis which suggests less downside both on revisions to EPS/FCF and the multiple from here.

- Excesses were sector and industry specific and less market wide. While some earnings may not have been durable the headline valuation metrics in the market didn’t reach bubble territory despite bubbles in things like crypto, EVs, SPACs, etc.

- A recession is not guaranteed. Consumer balance sheets are very strong and if consumers have been priced out of buying a home due to real estate prices or due to mortgage rates then they may redirect savings elsewhere.

- China is showing signs of opening up, alleviating supply and demand pressures. That and there are whispers that the Party at the very least will not be tightening the reins on the corporate sector further in the immediate future

- While lapping the fiscal stimulus is certainly an issue we are closer to the latter half of this headwind.

- As the rest of the world (specifically the ECB) catches up to the Fed’s tightening the dollar’s gains will slow, alleviating both earnings and economic growth.

- Sentiment indicators suggest investor optimism is at the lowest point in the last decade.

These are somewhat reasonable arguments but each one has its holes. Most of all they almost always are expressed from a position of defense and rationalization rather than objective analysis about what is going on, why, and what that means for possibilities. We live in a probabilistic world and if there’s anything market participants should learn and know is that capital markets are capable of surprise, both in direction and degree. Markets are far more resilient and adaptable than forecasters give them credit for, and forecasts tell you more about the forecaster than anything. But the possibility shouldn’t be dismissed at all. And so far, the sentiment seems to indicate that it’s not on anyone’s radar. That’s where the ammunition for further moves down in the market come from.