Reflecting over the last three years leaves us with a puzzling enigma: Is this a different world and a different market than the one we were facing in 2019? Unequivocally, the answer is yes, given the pandemic, along with the fiscal and monetary responses to it, the war in Ukraine, the tensions with China and the subsequent restraints related to globalization, the push for reducing carbon emissions and the products that come along with it, the new energy plays and the push for electricity, the inflationary pressures, and the higher level of interest rates, all of which unravel presuppositions, expectations, and plans. Nowadays, western countries openly adopt industrial policies (where, to some extent, the government picks the winning industries) while allowing monstrous debts to accumulate.

At the same time, both the US and Europe have experienced explosive political situations that have threatened their stability at a time when dreams of a democratic renaissance in other large countries are failing with a vengeance. Furthermore, looking into the future and at the dozens of millions of migrants who are expected to reach European shores in the next 10-20 years, we see a totally different picture from the one we are facing today.

How do we then invest in a market whose fundamentals are shifting? What do we buy now and forget for the next 3-6 years as the energy marketplace is changing? Which country is destined to benefit the most once the Ukraine war is over? And if these two simple questions help us to focus for the next 3-6 years, what do we do now?

Going back to the Roman times, we find two archenemies with totally different visions for their country who kept demonizing each other: Caesar who dreamed of an empire wielding its power for the people. Cato, on the other hand, wanted to protect the people from all-powerful empire builders that suffocated the freedom of the people. Their quarrel is not just an intellectual exercise. It led to the outbreak of a devastating civil war in 49BCE. That war set the foundations for the end of the republican government in Rome and ushered in the age of the emperors’ rule (finalized in Philippi in 42 BCE and in Actium in 31 BCE).

By the time the two giants (Caesar and Cato) had emerged on the Roman scenery, Rome had already started failing to produce great leaders. The historian Sallust writes that by the time of Caesar and Cato, it was evident that checks and balances were eroding, and that greater wealth had corrupted the Republic, its politicians, and its citizens. It was an age when virtually everyone in public life was determined to capture the Republic for himself and very few men of excellence were still around, Caesar, Cato, and Cicero among them.

Today’s changing geopolitical landscape may resemble the changes underwent in the years of Cato and Caesar. In this changing landscape, investment decisions should not be made carelessly by looking at the surface, but should be made by digging deep and assessing the medium and long term plays that will make a difference (like asking the questions of what will be standing in the energy sector and who the winners will be after Putin’s madness ends).

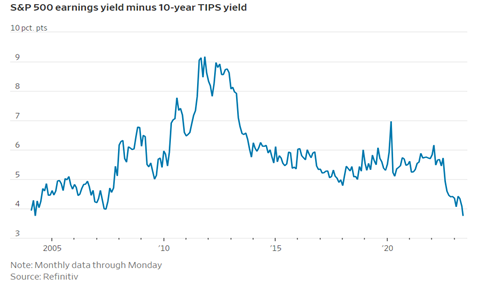

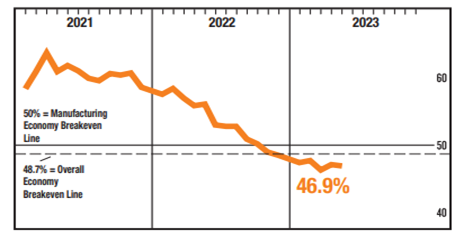

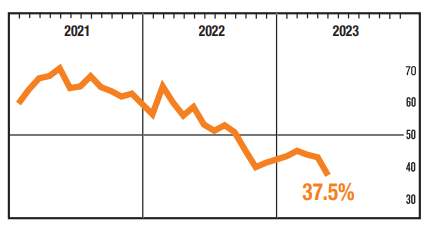

When we take a look at the graphs shown below, what kind of conclusions should we reach?

Are the graphs telling us that given the returns on fixed income, the potential returns from equities may not be worth the risks associated with stocks? Do the PMI and the Backlog of Orders (last two graphs) graphs foretell of a shrinking manufacturing/producers’ base that calls for caution?

We cannot deny that there are signs and indicators (GDP growth, housing activity, consumer sentiment, spending, employment, AI excitement) that the economy is getting better, and that recession may be avoided. However, we still have some serious reservations: The debt level is a serious threat especially in an environment of high interest rates and given the refinancing needs; commercial real estate is in trouble; the effects of high interest rates are not yet showing in the economy given the level of spending/dissaving that is taking place; lending is declining, and credit standards are tightening.

Caesar will end up crossing the Rubicon and conquering his own country with military force. Pompey will fight him to his death. Caesar will be assassinated by Brutus and Cassius who, in turn, will commit suicide at Philippi after losing the battle to Octavian and Anthony. Octavian will defeat Anthony and Cleopatra at the battle of Actium and will enter Rome as Caesar Augustus to honor his great uncle (Julius Caesar) and officially start the age of the Roman Empire.

So, what happened to Cato? Horace proclaimed, “all the world subdued, except for Cato’s defiant soul.” Cato became synonymous with virtue. Historians blame Rome’s civil war on the clash between Julius Caesar on one hand, and Cato along with Pompey on the other. Some were fighting for Caesar, others for Pompey. Cato was fighting for the Republic.