It’s the Capital Allocation, Stupid

It’s the Capital Allocation, Stupid

-

Author : Joel Charalambakis

Date : February 3, 2021

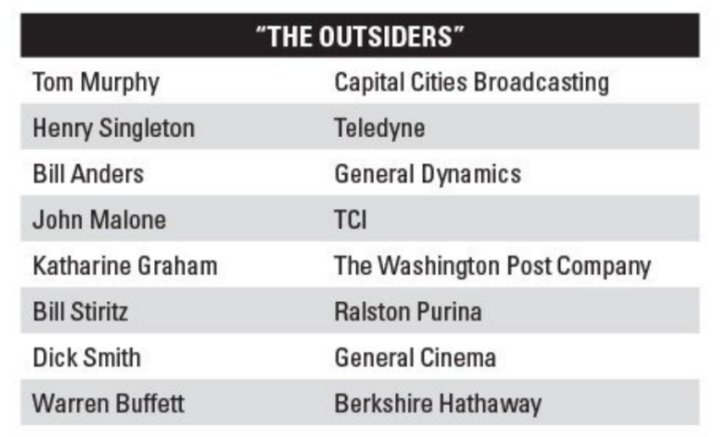

A student asked me for investing book recommendations a couple of weeks ago. There were several that I mentioned but the one I heavily emphasized is a book called The Outsiders by William Thorndike. It’s by no means a hidden gem (Buffett listed it as his #1 book in his 2012 letter) but it’s probably the most important book I’ve read related to my field in the last 5 years, if not longer.

The book examines 8 CEOs who don’t fit conventional molds of business executives, either in appearance, background or decision making. Whether it was their frugality personally and professionally, their shunning of public spotlight, or educational qualifications (only 2 had MBAs) the cast examined doesn’t fit the stereotype many of us have for corporate leaders.

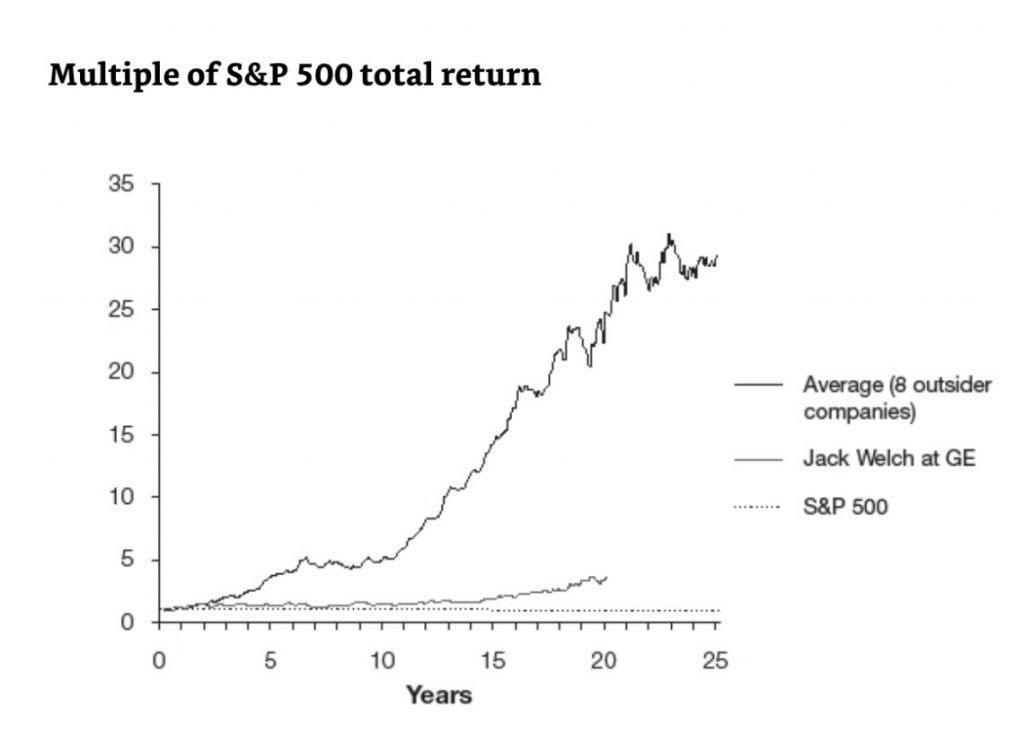

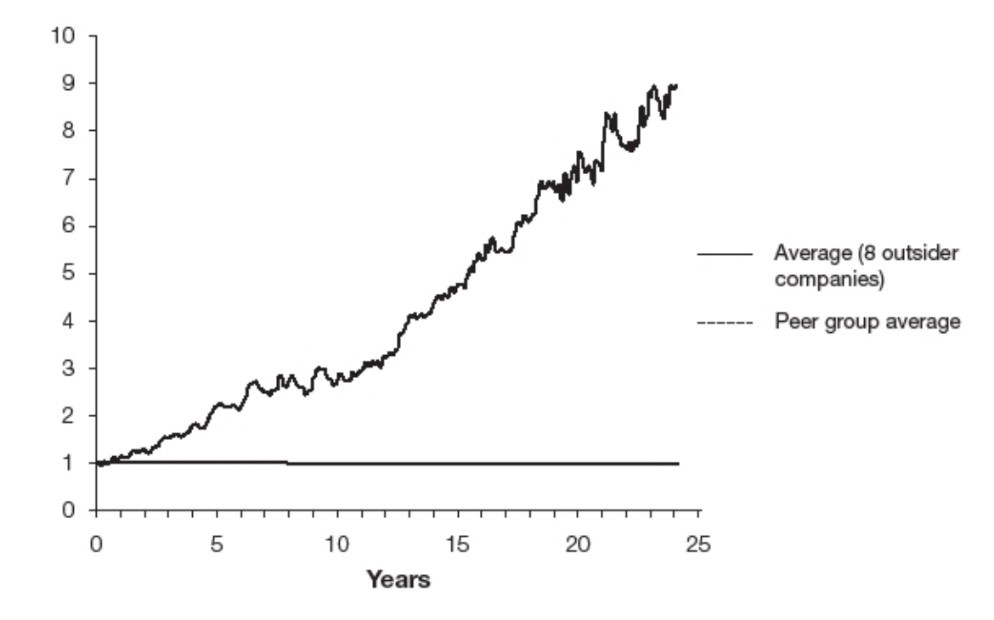

And that was their entire point. Being conventional, in their eyes, meant a fate dictated by the hand they were dealt (the industry they worked in, market conditions, etc.) rather than being the product of value additive choices made. The results of their management were anything but conventional (Figure 1).

Outsized Returns of Outsider CEOs (William Thorndike)

Reflecting back on the book in my conversation made me realize that over the past year my musings on Return on Invested Capital have examined many angles: what it encompasses, why it’s important, its connection to shorthand valuation, the relationship with a firm’s moat or lack thereof, how accounting standards mask value, and more. One aspect that hasn’t been broached has been the role of corporate management and capital allocation. It’s been touched upon at least implicitly (the importance of reinvestment, avoiding commoditization, destructive M&A etc.) and prudent capital allocation is a means by which the ends of superior ROICE becomes resilient. But even then, the topic probably hasn’t been discussed in the priority it deserves.

And yet, if someone asked me the most important job of a CEO I don’t think I’d hesitate and say it’s capital allocation by which I mean how a firm’s resources get deployed to maximize returns on a per share basis. As Buffett observed, “After ten years on the job, a CEO whose company annually retains earnings equal to 10% of net worth will have been responsible for the deployment of more than 60% of all the capital at work in the business.”

Regardless, it is far more common for a CEO to be involved in the operations of a business rather than concern themselves with the returns generated and what to do with them. After all, the majority of CEOs in corporate America today have spent their entire professional lives in some sort of operating capacity. They have backgrounds and decades of experience concerning themselves mastering a function, like finance or marketing. Again, from Buffett: “Once they become CEOs, they face new responsibilities. They now must make capital allocation decisions, a critical job that they may have never tackled and that is not easily mastered. To stretch the point, it’s as if the final step for a highly- talented musician was not to perform at Carnegie Hall but, instead, to be named Chairman of the Federal Reserve.” As an allocator of capital, CEOs must choose the best course with each dollar: to retain it and create more than $1 of value or to pay it out to shareholders in the most economical way.

Looking at the returns generated, or any familiarity with the names listed above, would make it quite clear that we are talking about a rare group that can be difficult to find. Yet I’ve found that almost as important as it is to take their principles to heart, is to ring the alarm on firms that fall on the other end of the spectrum with destructive allocation practices.

Below are some examples of commonalities found among these Outsiders and that should be sought and prioritized in the marketplace today.

- Cash is King

One of the most prominent takeaways is the weight placed on cash flow rather than earnings or profits. It’s cash that pays the bills and goes into employees and investors’ pockets, not accounting estimates. It solidifies the mentality that what I put into the business must come out in an economically attractive manner. Each Outsider by in large ignored GAAP earnings and instead maniacally focused on the cash produced by the business.

Several even had a single cash metric they adhered to in their allocation decisions. Katherine Graham of the Washington Post used Cash IRRs as a filter for deploying capital. Tom Murphy obsessed over cash flow margins. John Malone of TCI invented the term we all know today “EBITDA” to emphasize the rich cash generation and scale leverage produced by the cable industry. Meanwhile, Munger frequently refers to EBITDA as bulls*** earnings.

The polar opposite end of the spectrum is the General Electric of Jack Welch. Welch, hailed and revered as a manager, cared about EPS and only EPS and laid the cultural foundation for the demise of his conglomerate. By using the machination of his black box (GE Capital) Welch was always able to just deliver above his earnings promise by selling off some small assets here, engaging in financial engineering there, tweaking estimates left and right that were favorable per accounting. Over the last decade we’ve seen that game come home to roost (under other CEOs) as all those earnings weren’t bringing cash in the door, just kicking the can down the road.

Figure 2: GE’s Free Cash Flow Consistently Trailed Earnings

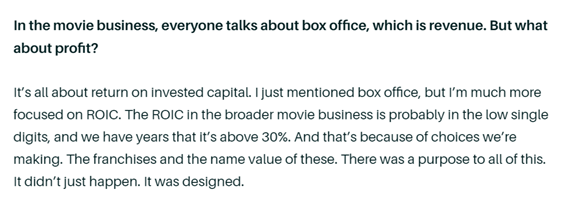

In today’s environment, just hearing a management team articulate a focus on cash and ROIC is rare enough. Pushing back on revenue or profits as key metrics and replacing it with ROIC is all the more difficult to find, which is why when I hear a management team talk about it my ears perk up.

Bob Iger on the Movie Business, Barron’s January 2019

2. Decentralize Operations…but Centralize Capital Allocation

One of the starkest traits of these firms and their leaders is their lean operations. Every one of them maintained as flat an organization as possible and pushed decision making authority down to people on the ground whenever they could. They believed that the people with the best information were those closest to the customer, whether that was another business or an end user. The closer business information was to the user the more valuable it was, and structuring the organization around maintaining the integrity of that information was paramount; corporate agendas, bureaucracy and other inhibitors were done away with. As Tom Murphy of Capital Cities stated, “hire the best people you can and leave them alone.”

There’s a humility inherent in structuring a massive organization like this. It’s the belief that corporate doesn’t always know best. And more importantly if a decision doesn’t work out feedback is both quicker and more direct. No one has to wonder if the idea was good and just poorly executed or distracted or meddled by someone higher up the ladder. Simpler organizations meant a faster diagnosis on how to improve going forward.

That said, while operations were as decentralized as possible, capital allocation was in the hands of a singular individual. This created consistency in philosophy and discipline in how decisions got made and by what qualifications. It also allowed those CEOs with multiple different businesses to be able to see across a broader opportunity set and pick the best place to deploy capital or whether the most prudent thing to do was return to shareholders.

3. Think and Act Like Owners

Every one of the eight Outsiders eschewed the Wall St. norm of issuing guidance for earnings or any other metric. It sent the wrong message internally and wasn’t consistent with an organization devoted to long-term returns. They didn’t act like a highly paid employee; rather they put themselves in the mindset of a long-term owner who was deeply connected to the prospects of the company they were leading. They behaved like they had skin in the game. In short, they were stewards of a company of which they participated in the ups and the downs.

Contrast that with some of the behavior I see all too common in corporate policy today. While a slew of companies have learned from the above models (and subsequent acolytes like Amazon and the SaaS universe) to emphasize cash flow over earnings they have gone off the rails with how they generate such cash.

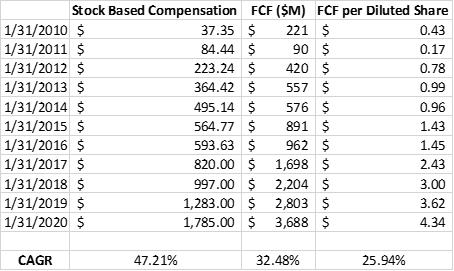

They follow a policy of “cash flow for me but not for thee.” Examine for instance the trends in Salesforce’s free cash flow. It’s a beloved company, compounding free cash flow at over 32% per year. Sounds great right? The problem is that cash flow is not going to you, the shareholder. Rather, it’s going to the corporate insider. Stock based compensation has grown at an astounding 47% per year for 10 years. Simply put, this is not stewardship.

Figure 3: Cash Flow for Me but Not for Thee

Is it any surprise then that the company has under-performed an index of software stocks on 10, 7, 5, 3 and 1 year time periods? The market knows what’s going on and the performance disparity has only gotten worse over time. Great management, via capital allocation, can elevate the resources around him/her whether those resources are human or financial by maximizing how far they go. But the returns provided by Salesforce come from the rising tide raising all software/cloud stocks, not astute capital allocation.

Returns as of Dec 31, 2020

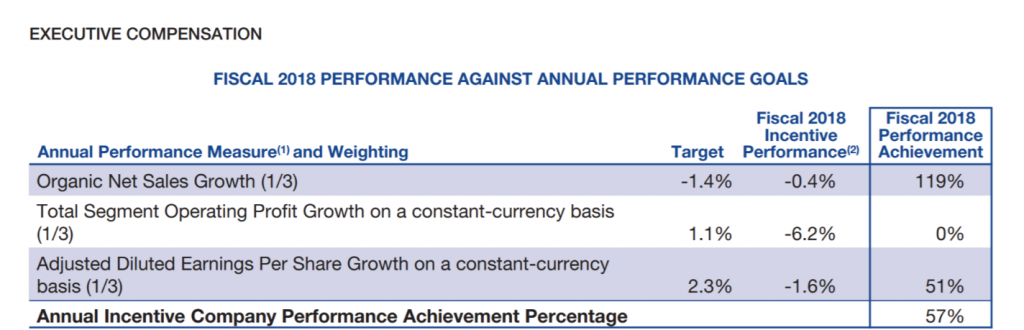

Of course, it’s impossible to think on behalf of shareholders and their well-being when the incentives aren’t there. Take a look at the incentive structure buried within the proxy statement from General Mills in 2018 (Figure 4). Would you feel comfortable entrusting your capital to someone who is incentivized to decrease organic sales? What kind of owner would set out to shrink their business?

Figure 4: General Mills’ 2018 Proxy Statement

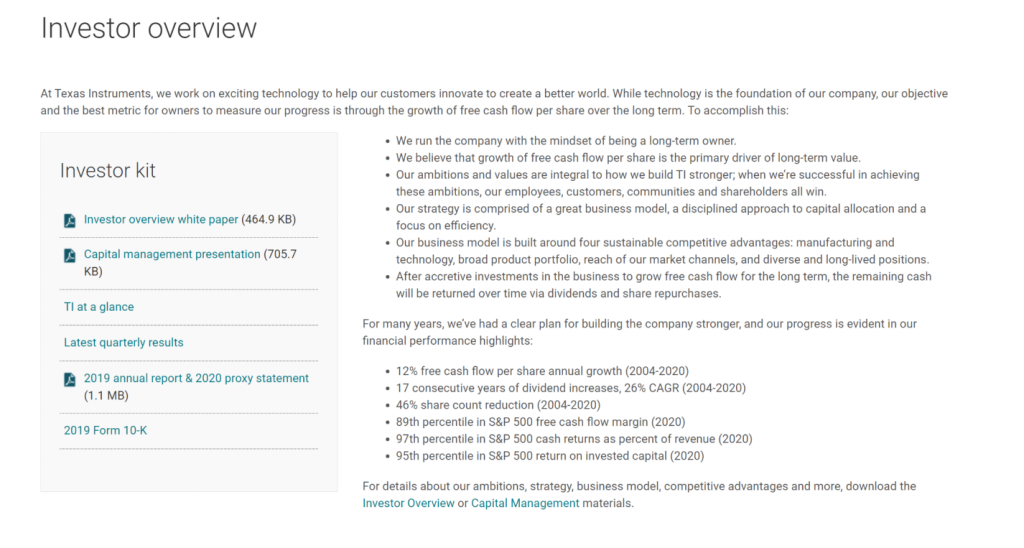

Most investors wouldn’t dig through a 60-page document on Board composition and management compensation (unfortunately) to find out whether there is real skin in the game. But contrast that with the attitude from Texas Instruments below. They have multiple sections of their Investor Relations website dedicated to capital allocation, how they think about it, their track record, and even resources that help explain their competitive advantages and various business segments in plain terms. I can count the number of companies I’ve seen with this sort of priority and transparency on two hands.

Who would you rather go into business with?

Does it guarantee TI is a worthy investment? Not at all. But the absence of thoughtful, cash flow focused capital allocation is a non-starter. There are no set rules as to how to approach capital allocation but given its dominance as a driver of long-term returns it does demand some level of thoughtfulness.

Bill Stiritz was a master at knowing when to buyback his shares because they were undervalued but also knew when it was overvalued and should be used as a currency. He was known for buying billion dollar businesses within 3 hours because his laser focus on cash generation informed his judgement on when to buy and how much to pay. Henry Singleton meanwhile bought back a shocking 90% of outstanding shares because it was the best use of capital (avoiding the taxation of dividends). But that was only after a decade in which he increased the share count by 14 times when it was a valuable currency. He used it to buy businesses and eventually grew EPS by 65 times, more than making up for any dilution. He was guided by prudent pragmatism, not rigid conventions. His buybacks alone generated returns of 42% per year and the corporate world looked at him like he was nuts.

Some Outsiders were heavily reliant on M&A by acquiring under-performing businesses, cutting costs and implementing better management techniques from prior learnings (Capital Cities). Others went through a heavy disposal of businesses before they could grow, shrinking intentionally, because of excess capacity but only doing so at accretive returns. In the process, they were increasing per share value (General Dynamics) despite becoming smaller.

If scarcity is one determinant of value then it’s pretty clear where more and more corporate leaders can separate themselves and the organizations they lead going forward. We have a generally good understanding and infrastructure for building managers of operations. That shows as generating free cash flow has gotten better in the corporate world over the last two decades. But what good is that additional cash if the person deploying it puts it to waste?