OPEC+ was born in the midst of the last oil crisis about five years ago. It expanded the traditional cartel of 14 nations and included Russia, Mexico, Kazakhstan, and few other oil-producing nations, all of which now control about 55% of global production and about 80% of proven reserves.

The weekend of March 7-8, a price war among OPEC+ oil-producing nations erupted. Saudi Arabia and Russia seemed determined to weaponize the Covid-19 crisis. Saudi Arabia demanded oil production cuts which Russia refused. In response, both nations increased their production, which pushed prices lower. The Covid-19 crisis has caused oil demand to collapse, and in places which lack storage capabilities oil has recently reached single-digit prices. This dramatic collapse – which will be much more painful for poor/developing export nations – has added to the financial markets’ turbulence. Moreover, it adds another layer of fragility to a complex system of capital investments and hence makes the downturn even worse.

Just two months ago, the US reached its highest oil production level ever at 13.1 million barrels a day. Due to the last decade’s shale revolution, the US is producing now more oil than S. Arabia and Russia, and therefore, the geopolitical stakes could be high. The dramatic decline in oil prices seems to be forcing the hand of oil producers and a summit is expected where significant production cuts may be decided (and hence the oil price increases we saw late last week, as shown below). However, no specifics have been determined yet regarding who, when, and how much oil production will be cut, which adds uncertainty to the whole endeavor, let alone the possibility of cheating on quotas.

In Phase I of the Covid-19 crisis, the world faced a supply shock (closed Chinese factories which initiated the oil demand crisis). We are now in Phase II of the crisis where the epicenters are the US and the EU (where consumption originates from). Hence, a supply shock now is combined with a demand shock, which pushes oil demand and prices even lower. Of course, for countries like Russia and S. Arabia oil prices even in the $30s create issues given that the former requires prices of around $44, and the latter needs prices to stay within a range of $76-80/barrel in order to preserve some stability in their budgets.

For the month of April, the projection is that oil demand will decline by about 20 million barrels a day. Even with a 15 million barrel per day production cut (which may stabilize prices), surplus oil will continue filling up the storage facilities. As storage facilities fill up, oil wells will be forced to shut down. Shutting down production – especially for US shale producers – implies that the country loses market share, which would be welcome by countries like Russia. US production is threatened by a cut of as much as 3 million barrels a day, according to IHS Markit, which by itself implies that around 3 million jobs will be at stake on top of the ones already lost. Such shut-in actions could inflict damage to reservoirs and production wells. To that we should add that in the oil business, lost market share is very hard to be gained back. If we add to that scenario the potential bankruptcies and bond (oil-related) market turmoil, then we get a pretty messy picture with economic and geopolitical effects.

As we discussed in our March 24th commentary, the gasoline crack spread has collapsed (indicative of the collapsing economic activity), and oil demand is expected to drop by 20 million barrels per day in April (from 100 million per day down to 80 million). The losses are due to the transportation industry (cars, planes, vessels), and lower overall economic activity worldwide. The magnitude of that shock will have enormous effects for the global refining system. Storage saturation for producers and refineries will create logistical issues. As producers are forced to shut down production, the contango phenomenon will be creating significant trading opportunities where traders buy today and sell in the futures markets, pocketing huge returns.

We are of the opinion that some form of an agreement (in which the Texas Railroad Commission that regulates Texas production could participate) could be reached in the next 2-3 days, which could stabilize prices between high $20s for the WTI and low to mid $30s for Brent. Such an agreement would aim to avoid a complete collapse that could see (in the absence of an agreement) oil dropping to levels around $15/barrel, if not lower. However, if lockdowns extend into the summer months, the impact of the expected cuts in production will fade.

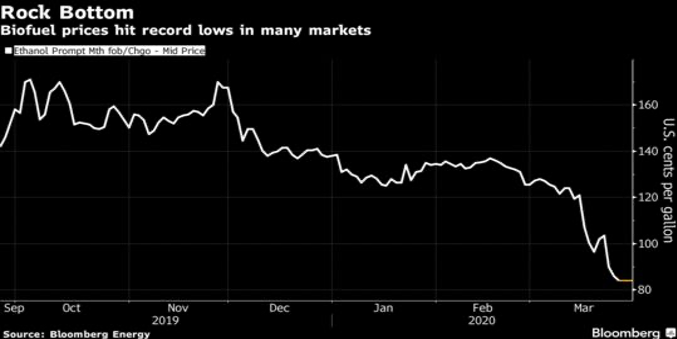

In another corner of the energy market, the biofuel industry is facing a reckoning (see graph below). The chronic oversupply and the trading upheaval is now matched by devastated demand that can wipe out smaller producers as well as those with heavy debt loads. Corn ethanol plants are shutting down. Valero Energy (the #2 US oil refiner) is closing down two plants. Pacific Ethanol is cutting production by 60%. Farmers who are selling one-third of their crops to biofuel producers face equally bleak prospects.

Some troubling symptoms in the oil markets possibly point to the awakening of undercurrent tremors. As stated earlier, oil is facing a storage problem that down the road may translate into production shutdowns which imply lost jobs, bankruptcies, bond market turmoil, while Russia may be gaining market share and geopolitical influence (we will be reviewing China’s rising influence in the midst of the pandemic in Part III). Moreover, given the November elections in the US, Saudi Arabia is considering the impact on oil prices if a Democratic candidate is elected and renews the Iran Agreement. If the economy recovers quickly (which we do not believe) we could start having energy-related inflationary pressures. So, while in the current stage we may be facing deflationary fears (and hence positive real interest rates which have consequences for fixed income asset classes), the oil sector turmoil along with the higher money supply, monetization of deficits, and the deficit spending itself may turn the tables and bring to the surface stagflation.

If a stagflationary shock were to happen, then old investment assumptions and paradigms will be turned on their heads. In a paradigm shift where inflationary pressures play a significant role, the valuation methods will shift and hence portfolios and asset classes will be changed dramatically. Asset prices will be impacted, investment styles will be shuttered, and investment strategies (let alone allocations) will become obsolete. In a shift like that debtors gain, creditors lose, and the middle class is undermined even more by the stagflationary forces