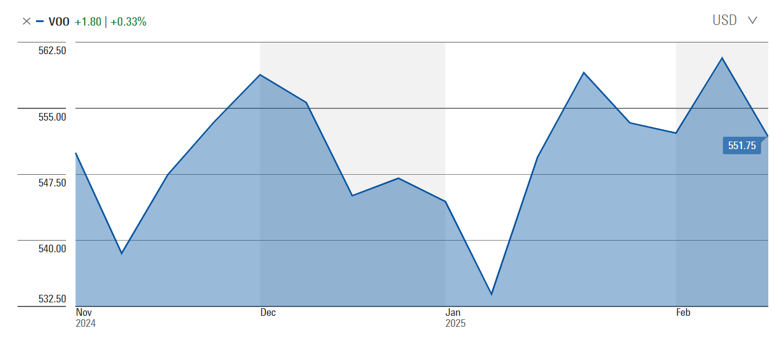

Last Friday, the significant drop in consumer sentiment fueled turmoil and led the market into a downward spiral that ended the day with a 1.7% decline, wiping out almost all gains since the election on November 5th, as shown below.

As our commentary two weeks ago described, sentiment volatility associated with institutional turmoil is a vital ingredient for rising uncertainty. The argument of this commentary – which could be considered a work in progress – is that the outcome of a reversal of the Bayesian Order while pushing the envelope in the Overton window (see descriptions below) increases uncertainty, undermines the moral code, and consequently reduces market returns, but most importantly undermines freedom and individual liberties. Consequently, the effects on the democratic process could be detrimental.

In her book titled The Theory That Would Not Die, Sharon Bertsch McGrayne walks us through the magnificent story of Bayesian statistics. Once we comprehend the significance of the theory, we can understand why it is crucial for stability, order, new discoveries, and progress in almost all fields of life. It is the theory that helped win World War II by being pivotal in cryptanalytic work, unscrambling German codes. It is the theory that was used to judge the authorship of the Federalist papers, has been used to search for nuclear weapons, assisted in the acquittal of Colonel Dreyfus, and is currently being used to determine the false positive rate of mammograms, just to name a few applications.

At its essence, the theory is simple: New information and evidence is used to update probabilities and beliefs. In investments, it helps investors adjust expectations according to emerging new data such as earnings, macro trends, rates, policy changes, etc. In geopolitical analysis, it is an instrument to adjust probabilistic expectations and strategy. In experiments and research, it helps scientists exclude failing hypotheses and reach correct conclusions. The posterior results help revise assumptions, modify beliefs, and ground us to reality. In market terms, we would say Bayesian order reduces uncertainty and helps us quantify risks while restraining volatility. We can all understand that a reversal of the Bayesian Order (e.g. probability of reversals in public health policy related to vaccines, probability of lowering the deficit by $1 trillion, probability of a reversal in the understanding of who the perpetrators are in the war in Ukraine, let alone who the criminal dictators are) could undermine progress and stability while advancing uncertainty.

The Overton Window theory explains how far public policy can go in terms of acceptance (from mainstream to radical reversals by adopting policies outside the normal range of mainstream conventions) by pushing into new directions and trying to shape public opinion and discourse in favor of the new direction, even if that new direction might have been unacceptable before (an extreme example could be the notion of the President declaring himself the King or taking on the title of Chairman of the Fed). Tariffs and a new global trading regime could be a more conventional example, and ignoring the court orders and the rule of law could be another, the policies of DOGE are certainly applicable, and of course, the contemplations about a new world order based on might rather what is right is equally applicable.

In economic terms and policy, pushing the tariffs’ envelope/policy (which could rise from a current average level of 3% to a level of 20%) could end up weakening the dollar, therefore undermining financial stability, which in a few months’ time could become the cornerstone of not just a market correction but of a bear market, especially if we take into account that US markets are priced for perfection.

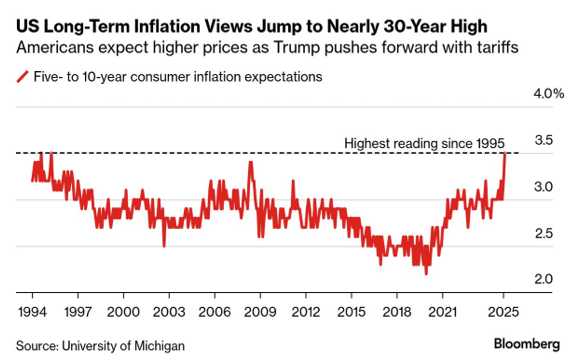

By walking back validated posterior assumptions and practices, and/or ignoring productive policies that have produced through time real positive results, and while experimenting with new unproven assumptions and pushing the envelope on new beliefs and policies, we may be jeopardizing stability by unlearning and invalidating the Bayesian Order, therefore rising the risk level and reducing market expectations. It could be that sentiment volatility is the prolegomenon to such an outcome. The wall of uncertainty could be approximated by looking into inflationary expectations, which are rising, as shown below.

The product of reversing the Bayesian Order while pushing the envelope on the Overton Window could resemble the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle (impossibility of knowing position and momentum with precision) in terms that the reversing of the Bayesian Order (position), even if succeeding in pushing acceptance of policies (momentum), could cap market returns. As beliefs are updated, sentiment and expectations are affected dynamically. As new policies attempt to reach political acceptability in an environment of updated beliefs and expectations, uncertainty could rise in a nonlinear fashion, which eventually could make the whole edifice of the geopolitical and geoeconomic system more fragile.

The shifting of acceptable policies (especially of fringe or extreme ideas by any political party) is capable of altering foundational values in society. If long-term norms and customs are pushed aside in favor of radical measures, then the dawn of degrading ethical standards that underwrite a free society and democracy could emerge. This is what James Q. Wilson calls the undermining of the Moral Order. The shifting of the norms that usually act as safeguards for society’s freedoms and for individuals’ liberties are derailed. If that were to happen, then the outcome of the reversal of the Bayesian order and the pushing of the envelope in the Overton Window will simply cancel John Locke’s ideas and what Immanuel Kant called “man’s release from his self-imposed tutelage” and will vindicate the irrationality of Rousseau.