“Don’t confuse genius with a bull market.”

HB Neill

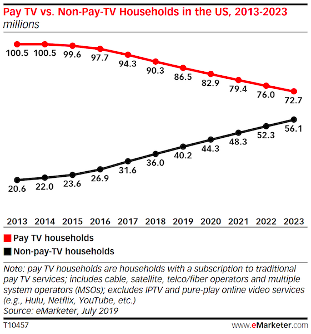

There probably isn’t an industry that historically gets more impacted by disruption than the media space. The current narrative and environment is well known to anyone: stronger broadband service, the convenience of on-demand viewing, advertising exhaustion, other entertainment options, and rising cable costs (especially relative to value provided) have all combined to decimate the Pay TV industry over the last decade (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Pay TV’s Steady Decline, eMarketer

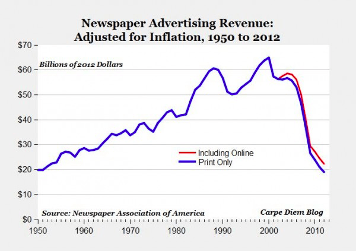

This is hardly the first time however that the media complex has stared a new medium in the face. Households used to subscribe to three newspapers per day in the early portion of the 20th century before the rise of periodicals took some share. Then of course TV accelerated the declining circulation of newspapers and periodicals as well (Figure 2). Despite the meaningful share losses, the newspapers did extremely well for decades (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Newspaper and Periodical Circulation Peaked in the Mid-20th Century…

Figure 3: …But Growth Lasted Another 50 Years

I find the two above charts fascinating. They show that profit pools emerge over years and decades. Further, they show that even during technological change futures are not linear; they are dynamic and, more importantly, not necessarily mutually exclusive. Television and the emergence of cable was an enormous threat to newspaper’s dominant advertising share. The latter was able to demonstrate some resilience. Not every paper survived of course, but the industry as a whole grew. Of course, it wasn’t enough to withstand the significant force that the Internet represents, which is why revenues peaked in 2000.

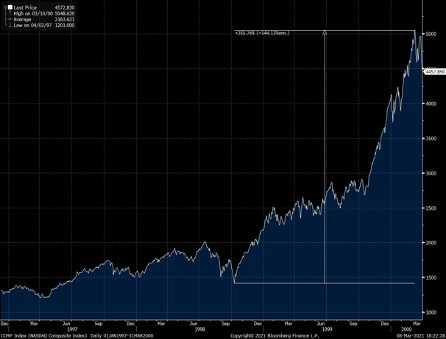

But let’s freeze that moment in time. It was quite clear to so many that the internet would be transformative but to be honest no one knew how big or in what way it would manifest. At the peak in 2000, Apple was closer to bankruptcy and being rescued by Bill Gates than it was developing the iPhone. Google was approximately 18 months old and Netflix about 12 months older than that. Neither was public. Facebook did not exist. The notion that Amazon could defeat Sears as a retailer was a literal joke to people.

None of that mattered to people. They bid up the market regardless of whether there were profit or business models were real and sustainable. They weren’t willing to wait to see how profit pools developed and value chains formed. It didn’t matter. The dream was so big and the opportunity imagined to be so transformative that the internet allowed enough room for all to survive together. That’s how dreams work: disbelief gets suspended and skepticism becomes a sort of social Scarlet Letter.

Figure 4: Nasdaq Dreams

But hope is not a plan. Eventually the market wakes up from the dream. The Nasdaq recorded a -58% return over the ensuing five years (Figure 5). Companies went bankrupt. Capital was destroyed. The Nasdaq didn’t reach its Dot-Com peak again for another 15 years.

Figure 5: Investors Paid the Price for Euphoria, Ensemble Capital

The funny thing is, investors probably undersold how transformative the internet would be in the future. That’s the nature of forecasting. It’s mind numbingly difficult. Yet, despite underestimating the gargantuan nature of their dream or theme, investors still got crushed. Few companies survived the crash and those that did needed a decade or more to grow into their valuations. In fact, of the largest components in the Nasdaq at the Dot-Com peak, only one has outperformed: Microsoft. The rest have meaningfully trailed.

Identifying a coming wave is frequently not enough. A rising tide can lift all boats, but not all boats are worth getting on. Computing exploded in the 1990s but the returns were concentrated in certain parts of the value chain (Microsoft and Intel) despite rising sales for companies like HP, Compaq, and others. Investing in “disruption” isn’t enough. It doesn’t tell you anything about a how a profit pool gets divided up and who captures most of that value. That’s even more apparent in markets of “disruption.”

Betting on any one company is often 3 bets in one, something I think people overlook: what will win, who will win, and how profitable it will be. Investors would rather reduce things to linear relationships and extrapolate “the obvious.” Which brings us to the circumstances of the market the last couple of weeks.

Below is a graph (Figure 6) of an index Goldman Sachs has constructed tracking the price movements of tech companies who don’t have profits. It’s not abnormal for companies without profits to either be in the public markets (many use them to raise capital after all). And the blunt instrument of GAAP accounting often fails to differentiate expenses between those that will bring in more cash in the future and those that support current operations. But even that has its limits. Over the last year, these companies have gone parabolic.

Figure 6: Goldman Sachs Unprofitable Tech Index

Digitization has been brought forward several years. And companies could acquire that demand at far cheaper rates than in the past; companies were knocking down the door to be able to continue operating in a remote world. They didn’t have to be sold.

But that doesn’t mean that every effort to digitize every process and transaction deserves an investment, let alone one at premium valuations. Sure, we’ll have electric vehicles one day. That doesn’t mean Tesla should necessarily be worth more than Exxon and Chevron combined. Nor does it warrant giving a company without any revenue a market capitalization of $30 billion (Nikola). And that’s before we even consider the fact that manufacturing automobiles has never been that great of an investment anyways. Could that change? Sure. But at these levels you’re betting on their inevitability, not their possibility. Are we sure the winners of EV penetration will be auto manufacturers? Could it be that a company licenses a service to each manufacturer and captures most of the profits themselves? What if concurrent to EVs taking share, consumers as a whole buy fewer cars, instead relying on automated taxis living in more rural settings? But why should any of those questions get in the way of some dreams?

Autos aren’t the only areas looking frothy of course. Telemedicine, green energy, and software have always been expensive but over the course of the last year their valuations have gotten out of hand. If they think a 20%, 30% or even 40% drawdown is painful (contrast that to the Nasdaq only being down 10%), then I hate to inform them that there’s the potential for far more pain down the road (Figure 7). Underwriting investments at these levels paint investors into a corner. They need a very specific future to come about to justify these valuations, a future with very high growth, very good profitability, and a clear picture of what the competitive landscape looks like, who wins, why they win, and by how much.

Figure 7: SaaS Multiples Have More Room to Come Down, W.E. Deming

So what caused all this? Why is this happening and why is it happening now? Is it the rise in interest rates? Is it profit taking? Is it just a normal market rotation?

Quite frankly, I don’t know. And I increasingly don’t think it matters. In fact, I think it misses the point. These are part of the inevitable fluctuations in the market. Trying to triangulate a monocausal explanation of a two-week phenomenon is just the other side of the same coin: it lacks humility, greets complexity with arrogance and hubris, and substitutes polarity for probabilistic thought processes. The restlessness to explain everything as soon as it unfolds isn’t much better than speculating on a wide-open future with a lottery ticket. There’s a lack of patience to let the competitive landscape settle, to see how different companies, management teams and business models react to the cyclical swings of a market and economy.

It reminds me of Pascal’s quote that “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” Investors may not be fearing the fullness of their souls but their inability to avoid dreamy temptations has them jeopardizing their wallets.