Emerging Markets Overview

Emerging Markets Overview

-

Author : Ken Rietz

Date : July 19, 2018

This commentary is an overview of Emerging Markets (EMs). We begin with a brief review of their recent trends, then explore common factors that affect most every EM (such as the strengthening of the USD), then look at factors that will affect different markets differently (such as the price of oil). Finally, we examine currency issues in some detail.

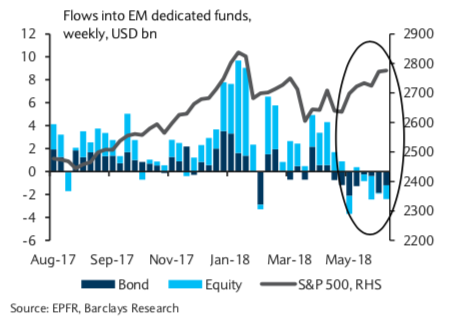

EMs on the whole have struggled so far in 2018. Starting out strong and building on a general rise in 2017, the emerging market ETF EEM gained more than 9% from Jan 2 to Jan 26. But all of that was rapidly lost when global markets toppled in early February, and it has wandered lower since then. Flows into EM-dedicated funds have been decreasing and actually turned negative in recent months, as shown in the image below. The obstacles that EMs face have not mitigated much, so it is expected that the EMs will continue to struggle into the third quarter of 2018, and likely even longer than that.

Of the factors that have pushed against all EMs, the primary one is appreciation of the US dollar (USD), spurred on by rate hikes and quantitative tightening by the Federal Reserve. The mass repatriation of USD has not materialized yet, but is generally expected to begin soon, and that will strengthen the dollar even more. Add to that, the European central bank is planning on ending quantitative easing at the end of this year. Plus, the recent spate of trade protectionism and potential trade wars has rattled most EM economies. Many EM central banks are hiking rates, responding to local inflation.

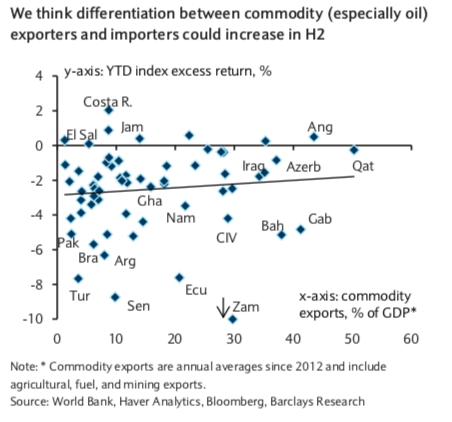

However, EMs are a very diverse collection. While there are a number of similarities across all these markets, there are probably more differences. Results of recent nationwide elections in several EM countries could lead to significant differences in their development. (Key EM countries with recent elections include Russia, Mexico, Colombia, Hungary, Malaysia, Brazil, Indonesia, Thailand, Egypt, and Turkey.) Increases in the price of oil will also have obviously different effects on oil-importing countries versus oil-exporting countries (see image below).

Currency turbulence has hit several EM countries within the past six months. At one point, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority intervened 13 times in a single week. Pakistan devalued the rupee by 5% in December 2017 and then another 5% in March 2018. The Russian ruble has recently suffered from US sanctions, and its troubles are unlikely to be over. Similarly, Iran’s rial dropped to a record low, despite governmental attempts to require a more favorable exchange rate. Turkey has watched its lira plummet also, spurred on by an increasing current account deficit. That same effect hammered the Argentine peso and the Tunisian dollar. This has set up comparisons of the EMs now to 2008 (by Carmen Reinhart) and the late 1990s (by Paul Krugman).

As money runs to the US, with its increasing interest rates and generally strong economy, central banks in EMs have often found it necessary to raise rates in order to lure money back, in order to ease the inflation that was taking hold. Bank Indonesia recently hiked rates by 50 basis points, the third raise in six weeks. BSP, the central bank of the Philippines, raised rates in two consecutive meetings, bringing its benchmark rate to 3.5%. Malaysia’s central bank raised its rate in January for the first time since 2014. Turkey’s central bank has raised rates 500 basis points since April. Brazil’s central bank is under heavy pressure to raise rates due to the truckers’ strike that has caused food shortages and the accompanying price increases. Mexico’s central bank just raised its rate amid concerns about NAFTA. Argentina’s central bank raised rates three times in a week, and its benchmark rate now stands at 40%.

Currency difficulties, combined with the strengthening USD, are creating a fragile environment for EMs. Christine Lagarde, managing director of the IMF, referred to this as “clouds accumulating on the horizon.” The GDPs of most EMs look to have peaked, making increasing debt more hazardous. Bloomberg described some EMs as “melting down” as recently as late May 2018.

There is no question that some EMs are in risky condition, but certainly not all. While India’s and China’s GDPs have been falling, they are hardly on the brink of collapse. Pakistan’s GDP is actually growing, from 3.7% in 2013 to 5.7% in 2017. These, unfortunately, are more the exception than the rule.