Disruption and the Second Derivative

Disruption and the Second Derivative

-

Author : Joel Charalambakis

Date : November 16, 2021

“Fish where the fish are” – Charlie Munger

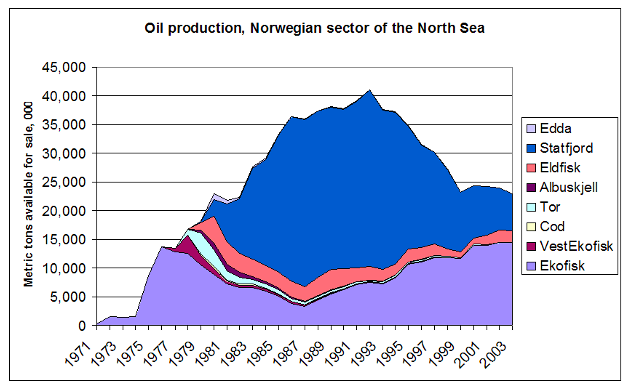

There’s an old story from the birth of the Norwegian oil market that has always stuck with me. In the 1960s the Norwegian economy was not a place that attracted a lot of capital. It was a subsistence economy built on the industries of timber, fishing, and agriculture. But in 1969, that would all change. An off-shore driller named the Ocean Viking struck oil in the North Sea. From then on, it was clear the simple life most Norwegians knew would never be the same.

Money poured into the country seeking drilling rights. Investors smelled a boom of wealth coming. The government sold off blocks of rights with little effort. It was about to become a global energy power.

Norway’s Oil Boom

Traders, investors, speculators all had Norway in their crosshairs. They obsessed over which companies would benefit most from this newfound wealth. They chased the headlines and the obvious trade. Valuations reached absurd levels. The majority of investors fell victim to the winner’s curse as the market had discounted the new wealth faster than they could get in.

Except for one trader. He sat back and thought about what this new discovery would enable. What new changes would be in store for Norway and its economy? How would some people behave differently now that they had been made millionaires overnight?

This trader realized that there would be a day in the not too distant future when all these oil men would think less about oil and more about their bank accounts. He realized they would start to express themselves with this newfound wealth. He realized they would buy art.

So, while everyone tried to pick up pennies in front of a stampede of other investors all chasing the same oil assets, he started to accumulate the best local art. Then he waited. When these freshly minted millionaires came looking for the best local art to display their wealth, he was ready to show them.

I think the story demonstrates a parallel to how investors should think about disruption and what disruption really means for wealth creation. True disruption is not a linear phenomenon. It is not a zero-sum game. It’s a positive-sum experience that creates new value chains, use cases, business models, and more. And that’s where the real wealth creation happens. To use our oil analogy: it’s as if to say the disruption brought about by discovering oil in the North Sea was that the timber industry would suffer because less wood would be used for fuel due to the former’s edge in efficiency. Sure, that’s a true and accurate statement. You might have even made some money if you got in soon enough and at a reasonable valuation. But you would have been correct for the wrong reasons. And the opportunity cost of where the real disruption was likely dwarfed your profits.

To put it more explicitly, I think history shows that the starting point for a disruptive innovation or technology happens at the second derivative. Specifically, disruption enables a new set of end-user choices, a new lifestyle, that wasn’t previously available or at least practical at scale. Disruption is not about shifts in market share from the old; rather it’s about unlocking something that didn’t exist before. And it’s a process that unfolds over decades.

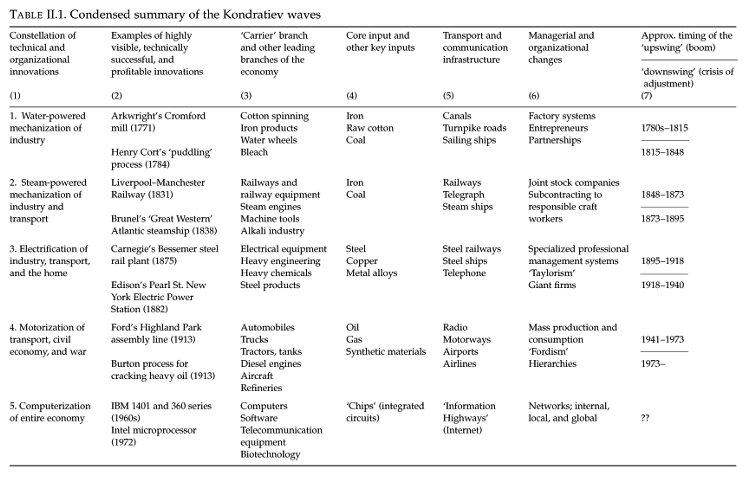

Take the disruption of the assembly line and mass production. Coupled with the revolution of cheap energy, the best opportunity was not in picking out machinery companies or auto manufacturers to invest in. It was to think about the lifestyle change that would ensue with the rise of a massive consumer class. Housing would boom, petrochemicals impacted everything from food to personal goods, appliances were created to replace work done by hand. The disruption and opportunity brought about by new industrial organization and cheaper energy extended far beyond those sectors. It unlocked the bedrock of the economy for decades to come.

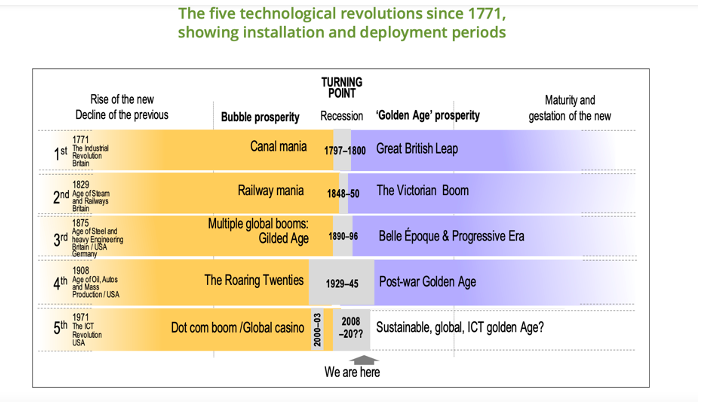

Carlota Perez, in her book, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital, outlines the Mass Production revolution and how it gave birth, with several other forces, to the consumer class. She outlines five technological revolutions or moments of real disruption and the commonalities surrounding each one. In each case, the point is quite clear that the impact of technological revolutions is felt far beyond the nexus. Yet, that’s precisely where investors spend the least amount of time.

Carlota Perez’s Five Technological Revolutions

If I could add an amendment to Mr. Munger’s quote at the beginning I would say, “Fish where the fish are, but where the fishermen aren’t.” If something is truly disruptive there’s no need to speculate; why look at the latest, of dozens, of EV related firms coming public with nothing but hype and a marketing pitch when everyone else is doing the same. There’s nothing to be gained by playing the same game as everyone else and hoping for better luck. If the hype is real, there will be adjacent effects that are even more powerful.

The first element of a competitive advantage in business is competing via some sort of differentiation. Investors should adopt the same mentality. Improve your odds by playing a different game.