Whether public or private, equity markets operate on the same underlying assumption – the investor is contributing capital now to participate in the future success of the company, at the risk of participating in its failure as well. Until that success is translated from the bottom line of the income statement to investors’ bank accounts through a dividend or return of capital, the investor derives no tangible benefit from their partial ownership of the company. It is, in effect, a piece of paper.

Thankfully for investors, common ownership brings with it the benefit of voting rights, and preferred ownership brings an assertion of dividends. Thus, if the company is successful, the owners may choose either to pay themselves or re-deploy that success to further enhance the company’s profitability in the future.

When operating properly, this system is excellent at creating value – a disparity between what you pay for something and what it is actually worth. Specifically, it creates tangible value – a financial benefit in the sense that you receive back more cash later (in real, risk-adjusted terms) than you pay now. There may be intangible benefits (predicting the future and being proven right creates a sizeable dopamine hit), but to a rational investor the measure of benefit must be cash.

The problem is that the public equity markets don’t seem to view the world this way.

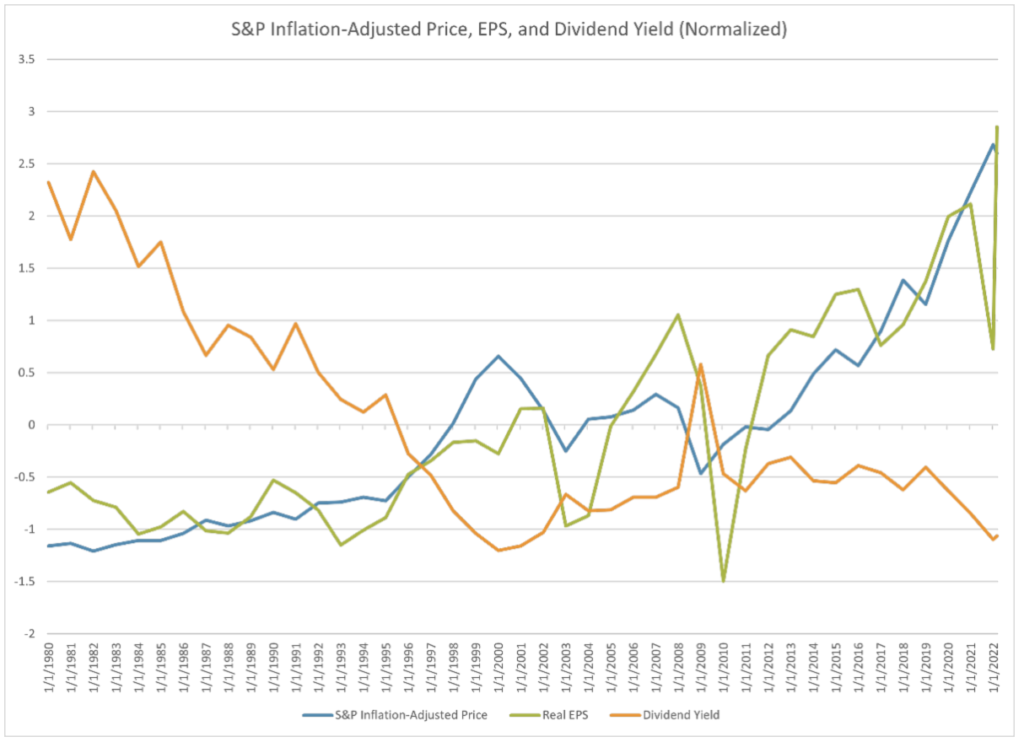

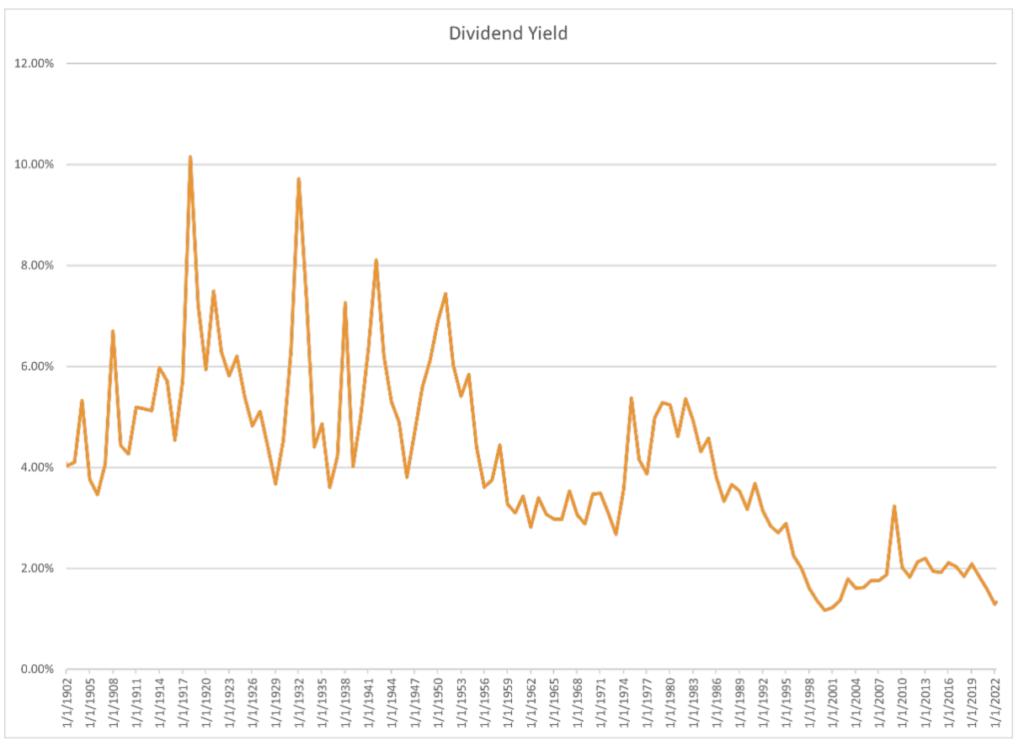

Since the mid-1980’s the dividend yield of the S&P 500 – the 500 largest companies in the US – has declined, while both the index price (implied valuation) and earnings per share (EPS, a measure of profitability) have risen.

If investors so obviously value future profitability over present dividends, it makes sense that company management would increasingly allocate capital to growing profitability.

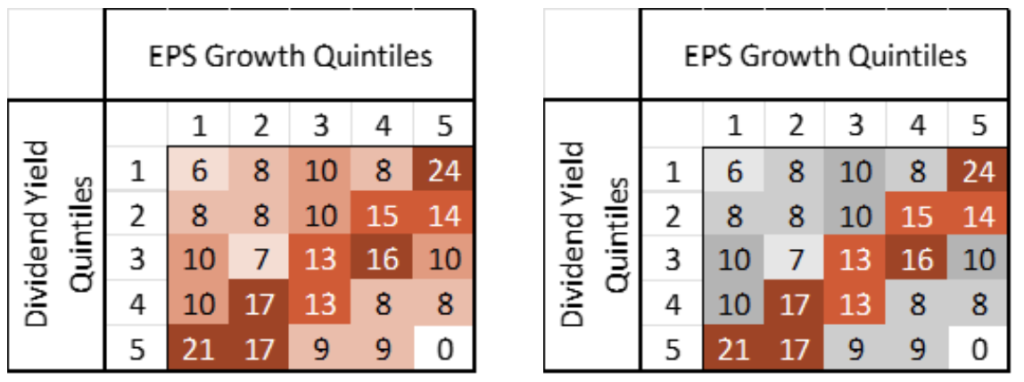

In general, there is an inverse relationship between higher growth potential and dividend yields, as illustrated in the matrices below.

Rankings of 279 S&P 500 companies with positive EPS growth since 2000. The horizontal axis represents the relative rankings of these companies according to median EPS growth, while the vertical axis ranks them by their 5-year average dividend yield. A ranking of 1 represents a lower value, while 5 is a higher value. The second matrix highlights an inverse relationship between higher EPS growth and lower dividend yields – over 50% of the 279 companies fall in this band.

On the surface, this is a healthy relationship – growing companies need to allocate capital to growth, while mature companies need to pay investors. The problem arises from human psychology – investors are conflating a company’s profitability with value generation. This is slowly moving the measure of a company’s value away from an intrinsic metric to an extrinsic one.

If expectations of profitability (rooted in a complex mixture of financial analysis, economic conditions, and human psychology) outpace a company’s actual ability to generate profits (rooted in supply, demand, and managerial efficacy), value is destroyed as the price paid for an asset grows faster than that asset’s benefit.

This is why a decline of dividend payouts is a concerning phenomenon – it signifies a willingness to delay realizing profits in hope of higher future benefits. That time difference creates risk, a risk which may not be reflected in company valuations.

If I buy a company because I expect to be able to sell it later at a higher price, I have not determined the value of that company, but rather the value that someone else will assign to the company later. This is reasonable if everyone has the same expectation of the terminal value of a company – the cash it will pay back to investors. But if the expectation of returns becomes unmoored from reality, someone will be left holding the bag. As long as the zeitgeist of the markets assumes increasing profitability creates value, there is a risk that the increased demand for these companies will destroy their value.