What’s wrong with the banks? How did we reach the point where three banks failed within a few days, and a couple more are on life support? How did we come to the point where close to $250 billion was wiped from the market value of US banks in about ten days, while one giant European bank (Credit Suisse) faced an existential crisis, while another’s (Deutsche Bank) survival was questioned last Friday?

The fact is that the pertinent bank indices in both the US and Europe suffered significant declines of over 25% in the last two weeks. Between the US and Europe, over $600 billion has been wiped out of banks and other financial institutions. When we add the losses of special bonds (designed to absorb losses in similar situations and thus rightfully so have lost all their value), then the aforementioned concerns along with the collateral damage and panic that the bonds’ write-offs can bring, we can easily conclude that red flags are raised not just among investors but also among savers and regulators.

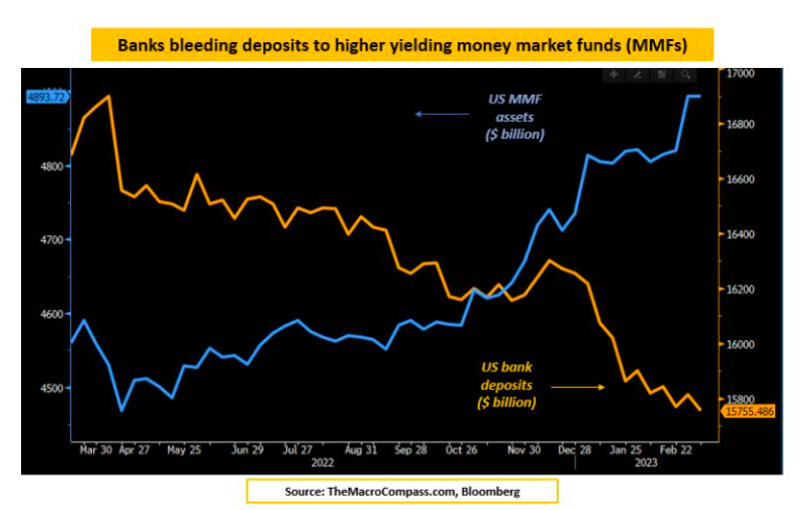

The following graph may summarize one underlying symptom that has been playing a significant role in these developments. Banks are bleeding cash as depositors search for alternatives that pay higher interest rates/yields. It’s called disintermediation, and we have seen this play out before in the late 1970s. High inflation leads to higher interest rates. Alternatives are developed (such as Money Market Mutual Funds), and so savers pull their funds from banks and deposit them into these alternatives.

As banks’ deposits decline, banks may be forced to sell some of their assets, such as US government bonds. The problem is that a chunk of those bonds are long-term bonds (such as 20-year Treasuries), and they have suffered losses in 2022 (due to higher rates and the law of gravity that states when rates go up, prices of bonds necessarily decline). Of course, it should be noted that buying those bonds in the first place – at a time when rates were ridiculously low – was very foolish. Consequently, those losses became real (they were not just paper losses), when the bonds were sold. As realized losses were reflected in the banks’ balance sheets, the banks’ own capital deteriorated.

Then, the word spread that banks may be in trouble. In an era of social media and e-banking, it doesn’t take that long for the word to spread which, in turn, creates panic, encourages people to move their funds, and thus deteriorates the banks’ liquidity even more. Consequently, the banks are forced to sell more of their holdings and absorb more losses, which in turn exacerbates the panic, and that forces a run on the bank. Eventually, the bank runs out of cash and fails.

The realized losses on government bonds ended up wiping out close to 25-30% of banks’ own capital and that, in turn, has elevated the concerns of a possible banking crisis. However, it needs to be stated that fraud, monkey business with overrated collateral, ridiculously low lending standards, toxic assets, tranches of over-hypothecated worthless paper/asset, and other similar very questionable practices were not involved in the unfolding events like in the 2007-’09 financial crisis (Credit Suisse never really recovered from the last financial crisis and hence its downfall should not be considered a surprise).

Are there regulatory deficiencies? Certainly! If the regulator doesn’t have the foresight to understand that banks are using clients’ money to buy long-term government bonds, which bonds may not carry default risk, but they carry substantial interest rate/duration risk, then they have failed in their fiduciary responsibility. Where were the stress tests on liquidity if the asset base of a bank suffers?

Of course, the government directly or indirectly has stated that all deposits are safe, including the uninsured ones, which has been the case in the past. So, from that perspective the banks are safe. Moreover, the emergency measures enacted (where banks can borrow funds from the Fed at face value of their government bonds, i.e., no haircut/no market pricing of those securities) has infused confidence regarding the viability, liquidity, and solvency of the banks. However, changes are needed to safeguard the financial system’s buffers, the capital cushions of large and small banks, as all of them base their business on other people’s money, on leverage, on over-extension of credit, and on counterparty risks, in an age where by a few clicks on the phone a regional banking red flag can turn out to be a systemic risk that can undermine financial stability.

What then could follow? The chances that we will soon see a lending and credit squeeze should be considered almost certain. That by itself is equivalent of an interest rate increase close to 1%. Consequently, the chances of a recession are rising. Furthermore, the credit squeeze will translate into lower hirings, if not layoffs. In addition, interest expenses and default rates will increase. Delinquencies will rise especially among zombie firms (those whose income doesn’t suffice to pay their interest expenses) which could lead to more defaults, corporate spending will slow down, expansions will decline, consumer spending will decrease and therefore corporate earnings will drop. In addition, more financial institutions may require government assistance both in Europe as well as in the US. If that is not contained, then we could have a medium size financial crisis (however, at this stage we believe that the chances are small).

The fear of recession along with the fear of financial instability should bring bond yields down (closing the spreads and reversing – at least partially – the inverted yield curve where short-term bonds pay more than longer-term bonds) and thus bond prices should rise.

Needless to say, all of the above are symptoms of three facts: First, central banks unnecessarily kept rates at almost zero level for too long; second, rather than allowing just the reserves to increase they made the lethal mistake of allowing the reserves to circulate as cash, and consequently permitting the money supply to increase substantially; third, they failed to see the forthcoming inflation and started raising rate too late and too reluctantly.

Their failures led them to raise rates aggressively, but the inflationary genie was out of the box in an economy that had been structurally altered in terms of demographics, customs, sectoral shifts, attitudes, and spending habits. Moreover, when they saw signs of breaking the economy, they didn’t pause to let the higher rates make inroads into the economy, but rather they kept pushing until the banks started failing. I am just wondering: If Volcker were alive and all these things were happening under his watch, wouldn’t that giant sage have the decency to resign?

And because we cannot be sustained by bread alone:

“Thus many of the relations that are most important to us cannot be captured by the terms of a contract: affection, friendship, love, all reach beyond the bounds of mere agreement, to involve a kind of unconditional giving to the other that might expect reciprocity but does not demand it. In effect, …we also find ourselves subject to bonds and obligations that are ‘transcendent’, in that they seem neither to arise from nor to be extinguished by agreement between living people. These bonds and obligations are endowed with an ‘eternal’ character.”

Roger Scruton, in The Soul of the World