Bundling and Unbundling

Bundling and Unbundling

-

Author : The BlackSummit Team

Date : June 15, 2021

In the mid 1990s Netscape Communications, one of the early darlings of the dot-com craze, embarked on a roadshow to meet with prospective investors prior to its IPO. In its last meeting, and already late to board the plane from London back to the States, management took one final, prescient question: what would happen if Microsoft just started bundling a browser as part of their Operating System? How would they compete? Jim Barksdale, the CEO, quipped in response: “Gentlemen, there’s only two ways I know of to make money: bundling and unbundling. We’ve got an airplane to catch.” And out the door he went.

The looks across the room, the story goes, were nothing short of confused. While Barksdale’s comments got them out of a time crunch, it had the added benefit of being true.

One business model in vogue for decades was to assemble disparate business lines under one roof: the conglomerate. The theoretical belief was that as a diversified set of businesses management teams could look across a broader set of investment opportunities and allocate capital to its best use and in a better manner than the market could. Their larger size also alleged cheaper access to capital. Companies like Sears started as a retailer but accumulated businesses in financial services (Dean Witter and Coldwell Banker), communications, credit cards, and automotive repairs. General Electric personified the model longer than most of its peers with exploits in entertainment (NBC), financial services (GE Capital was one of the largest players in the repo market leading up to the Global Financial Crisis), medical devices and more in addition to their classic businesses in aerospace or power turbines. Baldwin United sold deferred annuities in addition to its famous pianos. Eastman Kodak moved into pharmaceuticals. The list of examples would run quite long.

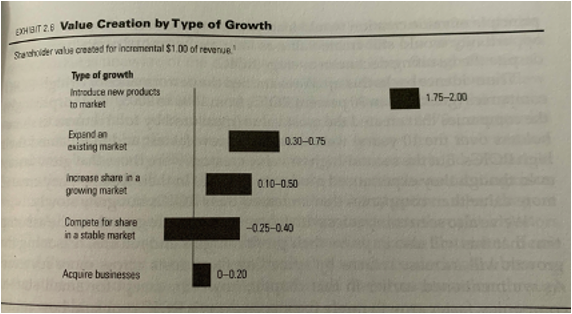

Like most mergers however, the superior value creation never came (Figure 1). Studies found that conglomerates were regularly discounted by 13%-15% compared to their peers in terms of valuation. Thus the moniker of the “conglomerate discount” was born. Unable to parse the web of corporate relationships, understand the underlying economics of each business line, and concern about excessive bureaucracy (and thus costs) investors greeted these corporations with skepticism.

Figure 1: M&A Is the Least Effective Way to Create Value, McKinsey

Conglomerates as an intentional business model died down for the most part over the last couple of decades as a result of the persistent discount; corporations simplified operations buying into the orthodoxy of specialization and efficiency. Companies like Tyco, Marathon Oil, ITT, Danaher, General Electric, Fortune Brands, Motorola, and many others restructured themselves in notable ways over the last thirty years. But just because conglomerates, as a model, were known as a liability at one point in time does not mean we won’t see the playbook tried again.

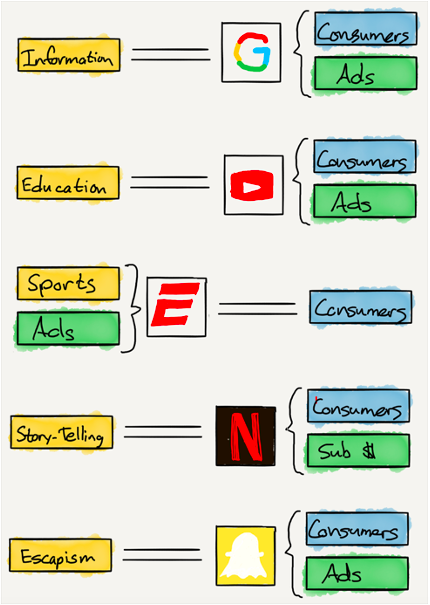

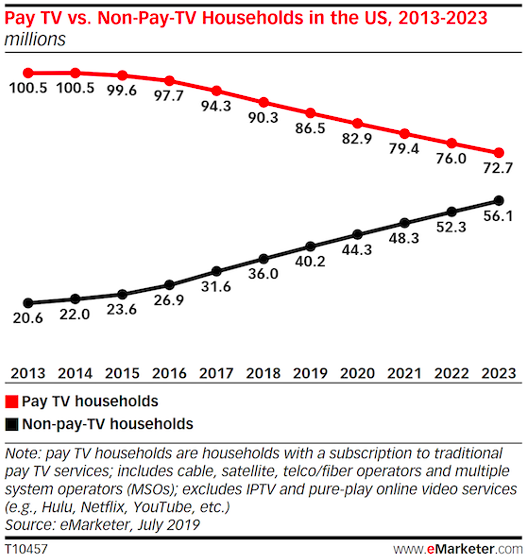

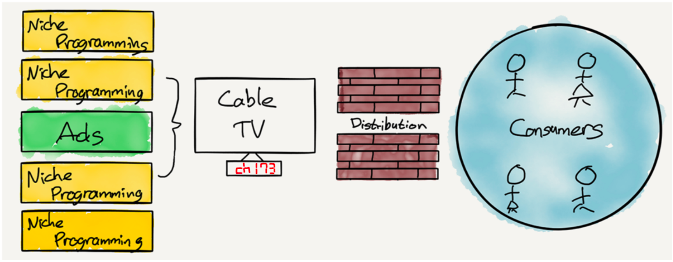

As the ubiquity of the internet took hold over the last decade many old industries and practices began to break apart and reorganized around new axes of value. Classic examples reside in the media world, both subject to the changes in the advertising industry. A high-speed internet connection now meant that advertisers could go directly to end users and the monopoly of distribution and attention that cable tv and newspapers offered now had much greater competition (Figure 2). The various functions consumers had for television (entertainment, news, sports, etc.) was unbundled into a variety of services all competing for user attention (Figure 3).

Figure 2: The Decline of Pay TV

Figure 3: Cable TV Unbundled Into Various Services, Stratechery

Payments is another area undergoing rapid change although end users only see a sliver of the changes. For decades banking was a bundle of payments processing as well as a source of capital for businesses and mortgages. Slowly that bundle is being reshaped. First, services such as PayPal abstracted away the plumbing involved in moving money around. It was an ideal solution for the digital age as ecommerce was in its infancy and trust of inserting confidential financial information on the internet scared many would-be shoppers away. Since then additional services that were either directly a part of the original bank bundle or ancillary financial processes emerged to meet consumer needs: peer-to-peer payment, point of sale systems, financial advice, merchant acquiring, inventory financings, payroll, and mortgages have since been stripped out of traditional banks into stand alone functions. While most vendors in the space only offer singular point solutions (with a couple of notable exceptions) the digital world’s ability to connect bits and bytes involves much less friction than the analog equivalent; so long as the experience is superior to that of a traditional banks by a large enough degree these new firms can overcome the bundled offering of traditional players.

Figure 4: The Unbundling of Financial Services, Marc Rubinstein

But where this unbundling of financial services gets more interesting is what it portends for the future. Earlier this year, Square launched its own bank. The company has been moving up the financial ladder to more and more high value-added services. From its start by helping small merchants accept card-based payments Square’s software moved to helping small businesses manage inventory by being able to integrate purchase data. Other features (invoicing, payroll, corporate cards, etc) soon followed. The company has built out consumer products as well to accelerate its ecosystem. Its multiple touchpoints mean a broader and complete data set from which to base underwriting decisions and take share from traditional banks. The bundle has come back full circle and it looks to be stronger than previous iterations with better underwriting and more satisfied consumers.

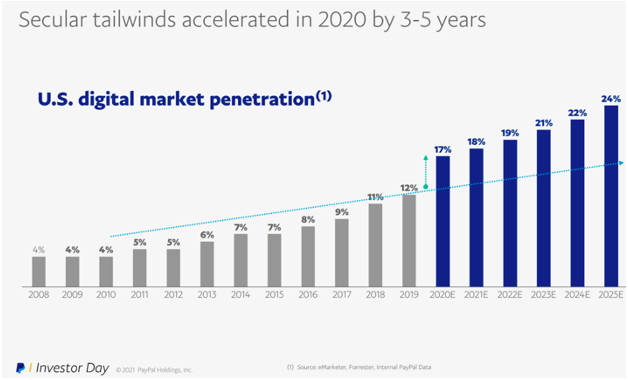

Figure 5: The Digital Future Was Accelerated

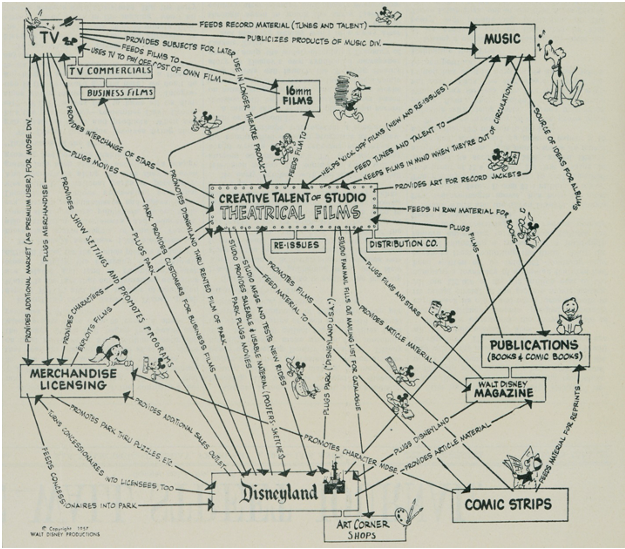

Covid-19 accelerated digital experiences of virtually every type, payments especially (Figure 5). The transmutability of data sets up the possibility for the return of the conglomerate. Of course, it’s not a certainty but if you squint or keep your ear to the ground low enough some early rumblings are apparent. There’s the rumblings of Apple and automobiles, Nintendo opened a theme park in Japan, Netflix eyes video games, and of course Disney has worked towards its founders original vision for years now (Figure 6).

Figure 6: The Original Disney Bundle circa 1957

The zero marginal distribution costs of the internet age means reaching potential customers from different cohorts and segments is easier than ever before. And armed with first person data building new bundles that weren’t previously imaginable are certainly possible. Will it work? I’m skeptical but who’s to say for certain? This may all be for naught anyways. But who would have thought that you could build a communications business on infrastructure provided by a company that will also ship whatever you want to your door in two days. My hunch is that those are more exceptions than the rule. M&A of related industries is hard enough as it is; tangential businesses are more difficult; completely disparate offerings require a special blend of culture, discipline, patience, humility, and vision.