Machiavelli stood in one of the corners of the famous square convinced that nothing fails like success. The calendar read May 23, 1498. Outside Florence’s city hall – the famous Palazzo della Signiora – a long scaffold had been built. A great throng of people had gathered to participate in the burning of Savonarola and his top two aides. The hero of the city would soon be the great zero and would be added to the ashes of the city. A few years earlier in 1492 (the same year that Columbus sailed to the New World) and upon the death of Lorenzo the Magnificent, Savonarola had called the people to rediscover their freedom and their inner liberties – as they experienced them in 1402 – that they so much treasured but had lost during the Medici reign.

Almost two centuries earlier, Florence was the only city-state that was resisting the mafia-don style of government that the Visconti family had imposed in northern Italy since the early 1300s. The Visconti coat of arms was a serpent eating a man. In 1399, Gian Galeazzo Visconti set out his coils to encircle and devour the resisting city-states of Perugia, Pisa and most importantly Florence that stood alone against his tyrannical rule and his propaganda machine of making Italy great again, as in the times of Caesars. Visconti was calling the rest of northern Italians to help him subjugate the Florentines who, in the name of liberty, were resisting his force and will.

At a time of higher inflationary pressures, investors are buying TIPS (Treasury inflation-protected securities whose payout at redemption is tied to inflation) for a negative yield. Bizarre, but nothing fails like success.

Caluccio Salutati was Florence’s chancellor/city manager. He searched for ways to counter Visconti’s propaganda machine and re-inspire the citizens with a renewed respect for that libertas: the right to run one’s affairs as one sees fit. Salutati was a learned man and he found what he needed in the works of Aristotle, the spokesman for the ancient polis, the one who had inspired Cicero. Salutati and his successor Leonardo Bruni re-discovered and inspired the Florentines with a simple message: that the highest form of life was that of a householder, who “as a citizen shared in the civic life of ruling and being ruled in turn.” In Aristotle they re-discovered the ultimate balancing factor that every constitution is required to have: the One, the Few, and the Many. And all these rediscoveries were needed, because as they read in Aristotle “the end of the state is not mere life, it is rather, a good quality of life.”

Only under liberty could persons realize their true nature and potential as human beings who are not just free individuals for themselves, but their freedoms are part of a greater whole. That is why and how the Athenians had defied the tyranny of Persia against all odds. This was why the early Romans had risked everything to overthrow their kings, so that they could live free.

As the Venetians were signing “peace agreements” with Gian Galeazzo Visconti, and as the Bolognese forces were subdued in the battlefield to Visconti’s forces, the Florentines decided to keep fighting. And then suddenly, on September 3, 1402 Visconti was subdued by high fever, died and his empire crumbled away.

When exercising policy, cohesiveness and strength assumes an internal virtuous balance of the One, the Few, and the Many. The result of this unexpected turn of events in Florence? An upsurge of confidence and energy in all aspects of Florentine life. That same year, Brunelleschi and Donatello went to Rome to study classical architecture. Upon their return a year later, they started working on the great dome of Florence’s cathedral. A massive creative outflow was born in the arts, in literature, in architecture and, naturally, Renaissance followed. Aristotle’s politics of freedom signaled the birth of a new ideal for all of Europe. Leonardo Bruni will write of this epoch: “liberty exists for all, the hope of winning public honors and ascending is the same for all, …so that talent and industry distinguish themselves in the highest degree.”

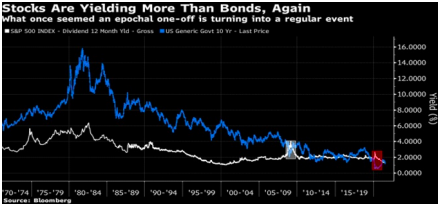

The time when stocks are yielding more than bonds and the spread between them turns in favor of stocks, may provide us clues of a paradigm shift where traditional balance is rejected.

When the famous artist Vasari was asked why all the key ingredients of Renaissance culture first appeared in Florence he replied: “the air of Florence making minds naturally free, and not content with mediocrity.” Well, that liberty did not last. By the time Leonardo Bruni died in 1444, history began mourning. The Medici’s had started their rule about ten years earlier. Now, Florence was experiencing its own soft power of Visconti tyranny, with meritocratic virtue gone and where money talked. Consequently, since money talked, everyone was condemned to listen.

Machiavelli was standing in the shadows of that square’s corner that fatal morning of May 23, 1498 contemplating why freedom failed in Florence, and prior to that also in Athens and Rome. We, too, along with him today would say it has also failed in numerous other countries since then. The crowd was cheering as Savonarola’s burning flesh was filling the square’s air and Machiavelli – who had been a follower of Savonarola – had started contemplating some uncomfortable questions.

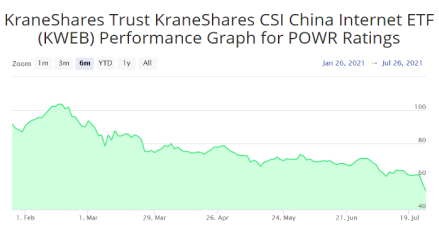

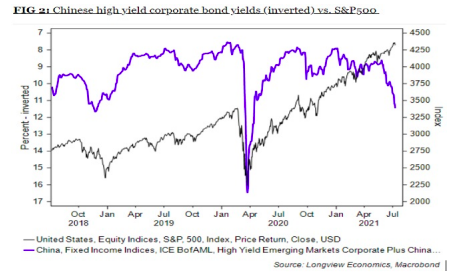

Speaking of uncomfortable questions, one cannot neglect the fact that Chinese internet-related stocks have tumbled close to 45% in the last six months, while Chinese high yield corporate yield portrays a pretty uncomfortable reality about Chinese policies but also Chinese corporate credit, as shown below. A reversal in the co-movement is taking place which may signify that Chinese companies may be facing a Prato day.

Niccolo Machiavelli had been bred in the ideal of civic humanism. He never knew a time when the Medici’s had not run the city, but his paideia had led him to Savonarola and he lived through the rebirth of the republic when Savonarola was its head. Machiavelli was no armchair strategist. For close to fifteen years, he had negotiated with the pope, the kings of France and Spain, and the sinister Cesare Borgia. Starting in 1506, Machiavelli was put in charge of Florence’s militia. Then came the summer of 1512 at Prato. Machiavelli’s men in the second Spanish attack dropped their swords and fled. Prato fell to the Spaniards. Florence followed immediately after that. The Medicis returned to power and Machiavelli was ostracized, tortured, and experienced the infamous strapado.

The reality of the political world has very little to do with Plato’s Philosophical Rulers. Rather, as Machiavelli elaborated in his book Discourses (borrowing from Aristotle and Polybius), the freer a society becomes, the more prosperous it grows, and the more prosperous it becomes the more arrogantly it behaves. Prosperity without virtue and paideia sows the seeds of servitude. The Romans has read Polybius who, in turn, had absorbed Aristotle’s message that unless a balance of monarchical, aristocratic, and democratic values (the One, the Few, and the Many) is constantly monitored and reinvigorated, society is doomed to fail. He will write in the Discourses: “All human affairs are ever in a state of flux and cannot stand still.”

According to Machiavelli, the elements that empower a free society (trade, vigorous politics, strong military) ultimately turn back on themselves. Prosperity and success become passions for elevating private vested interests rather than the interests of the State, which, in turn, corrupts its institutions and consequently, the society fails as factionalism and tribalism prevails. When each member of the group in the mix of One, Few, and Many is devoting itself to gain power at the expense of the other, then life (economic, social, political) becomes a cycle of mafia-style vendetta and payback. In the meantime, luxury and wealth cover up the internal cancer/corruption of the institutions’ soul and death becomes unavoidable. New legislation cannot help “the new laws are ineffectual, because the institutions that remain constant, are corrupt.”

When society has come to that point, only a crisis can awaken the society and that’s where a Prince is needed to save it from extinction. The Prince cannot be a Platonic soul doctor and cannot be a high-minded Philosophical Ruler. The Prince is nothing but an aisymnitis who knows the art of war and is using all means necessary to save the State from its forthcoming collapse. Machiavelli had just discovered that Aristotle’s Politics is built on the back of his Ethics. The good life presupposes a virtuous life. However, survival may dictate stopgaps and temporary suspensions of the values they profess to uphold, when the Prince’s mission is not to please the masses and be loved, but rather inflict pain where necessary.

Somewhere in the distance, Machiavelli saw Isaiah Berlin smiling.