In last week’s commentary, we outlined our overall assessment of a decent start for 2020, but expressed our skepticism for the rest of the year (see Assessing the 2020 Outlook: Part I ).

The upbeat perspective of most of the analysts for 2020 is based on loose monetary policy, consumer and government spending, and hopes for a comprehensive trade deal with China. We partially agree that the first three may boost the economy temporarily, but we are not optimistic about a comprehensive trade deal with China. Moreover, we are of the opinion that loose monetary policy and government spending (with the exception of solid infrastructure spending) undermine long-term growth.

We believe that a number of factors following the financial crisis of more than ten years ago, have been fertilizing the ground for the next crisis whose first signs may start popping up by late 2020. Let’s elaborate on a few things that elevate our skepticism for the second half of 2020.

For close to 50 years now we have been experiencing declining productivity growth. The deterioration has been exacerbated in the last several years as shown below.

The symptoms of such decline are stagnant incomes, rising economic inequality, resentment, populism, a backlash against classical liberalism and globalization, misallocation of resources, and boneheaded remedies and policies, among others.

The monetary policies implemented back in the 1870s (removing bimetallism as the monetary regime) created a panic and the first international crisis of the modern era. Of course, it would have been a significant omission if we had failed to mention that some forces at display back then are also at work today, such as elevated globalization (the period after the 1870s was the first truly era of globalization), deflation/disinflation, and technological leaps. Those forces are often mutually reinforcing.

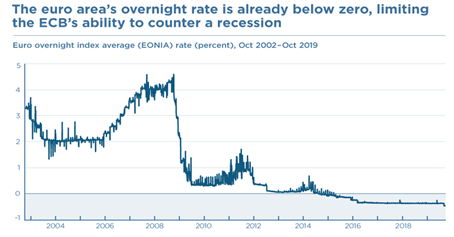

The enigma within the dilemma of monetary responses to an unsustainable structure created by debt, unfunded liabilities, and the derivatives Frankenstein can be seen in the next two graphs:

The first one reflects one of the symptoms of that unsustainable structure. The second does the same thing, but also sends the warning that the system can break at any time.

The negative interest rate regime that several European central banks have adopted has not only sustained an untenable European banking system but also imputed distortions in capital markets. On this side of the Atlantic, the sudden rise in the repo rate (see graph below) forced the global lender of last resort (Fed) – either because of cash squeezes, potential financial tremors, addressing the consequences of tightening its balance sheet, or a combination of all of these – to start intervening in the markets on a daily basis injecting liquidity to the tune of at least $70 billion every day. The repo market is the lubricant that keeps the wheels of the financial system spinning, otherwise short-term cash needs cannot be met.

Could the incident of last September be a prelude to similar incidents in the next couple of years? Are there enough tools to address the unexpected? The cancellation of bimetallism in the early 1870s disrupted the markets and the effect of that was depression.

Beyond developed economies, we are watching the dangerous levels of debt in developing countries whose liabilities make them significantly more vulnerable than even before the financial crisis. China’s warning signs are flashing almost everywhere. Runs on rural banks go unnoticed. Surging consumer indebtedness is neglected (household debt is 99.9% of disposable income). Corporate debt stands at about 170% of GDP. Bond and loans restructurings are not reported at a time that Chinese authorities urge local governments to speed up the issuance of more bonds (obviously in an effort to bolster economic activity)! Regional state-owned enterprises are struggling. Creditors have start experiencing losses. Recently, China’s Central Bank (PBOC) admitted in its Financial Stability Report that about 15% of the banks are classified as high risk. All of these at a time when the economy is slowing down.

Who could exclude a spike in rates in China that would tumble both debt and equity markets?

Elsewhere around the world, we could observe the following:

- In Canada, GDP growth is expected to rebound in early 2020 due to real estate strength and the loosening of financial conditions. However, we expect the growth will slow down by the end of 2020.

- The EU is expected to loosen policy further in an effort to sustain the unsustainable.

- UK politics will hold the economy back.

- The Japanese economy may experience a recession and we retain concerns about the Japanese financial system.

- The Swiss and Nordic economies are expected to continue being weak.

- Growth in Australia and New Zealand is also expected to slow down and the Australian Central Bank is expected to lower rates.

- India faces further political turmoil, which may slow down the expected upswing.

- Emerging Asia (other than India and China) should experience higher growth due to loosen policies, capital inflows, and consumer spending.

- Eastern Europe is expected to exhibit higher growth rates.

- Latin America should also exhibit decent growth with the exception of Argentina where debt write-down and inflation will continue undermining the economy.

- The MENA region is expected to show some new growth signs but the situation in Lebanon is heart-breaking where a combination of debt, banking and currency crises may devastate the economy.

I was looking for an escape and decided to take the road to the airport to board my end-of-year-flight. Along the road, I was looking for a palace but bumped unto a stable. I was told that kings and queens were coming to pay tribute. I could only find poor shepherds. The baby of the stable later was found as a refugee in Egypt, and in his later years was supposed to enter the city on horse, but he decided that the donkey was sufficient. Somehow, that stable’s message still shatters the long-standing categories of weak victims and strong heroes. The victim emerged as the hero.

Merry Christmas!