“The three most important words in investing are margin of safety.” – Warren Buffett

There’s been an alphabet soup of hypothesized recovery patterns over the last two months as the economic consensus came to grips with the impending recession in the U.S. L, U, V, W patterns have all been mapped out and debated as to which is the likely shape of the economy and the stock market over the coming months.

In a similar vein, we decided to look back at previous economic contractions and bear markets to see, not so much the shape of things to come, but their timeline, and to see what that says about the supposed sustainability of the market’s rally since March 23.

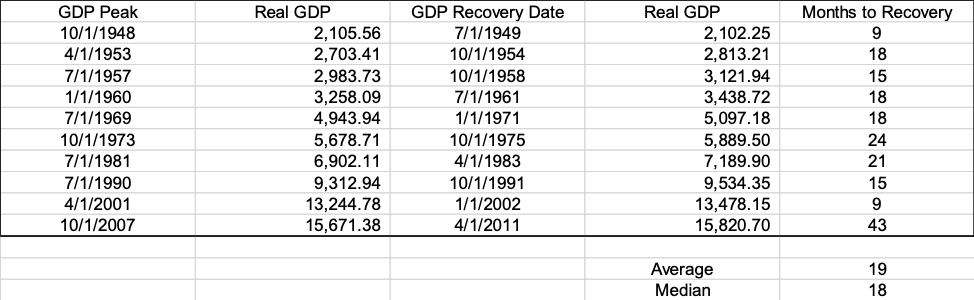

Figure 1: GDP Peaks and Recoveries since World War II

In Figure 1 above, we’ve listed the dates in which Real GDP peaked before an economic contraction, followed by the date when Real GDP caught up to the prior peak, and the number of months in between. Going back to World War II, it’s clear there is no consistent path to how the economy has recovered falling a downturn. There’s quite a bit of variability, with the recovery out of the Financial Crisis taking 43 months to reach its October 2007 levels while the dot-com bust era only needed 9 months to recover.

Of course, the market is not the economy and the two can diverge for substantial periods of time. As we mentioned in a prior commentary, despite the optimism heading into 2020 a number of fundamental indicators (Railcar loadings, Leading Economic Indicators, the ISM Index, etc.) portrayed an economy that was on fragile footing. But a history of bear markets over the last 40 years suggests that the two are quite related (Figure 2).

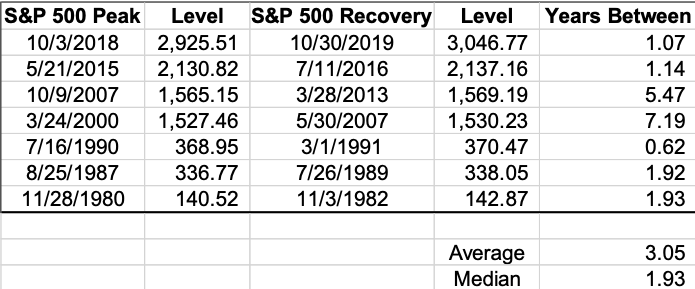

Figure 2: S&P 500 Peaks and Recoveries

Again, the variability shows nothing is guaranteed but the vast majority of cases shows that the market needs at least a year, if not multiple years to get back to prior levels. The median and average path back actually corresponds quite nicely to the pace of GDP discussed earlier. For those expecting a “V” shaped recovery, whereby the economy is back and growing again within 6 months, the data from history simply isn’t very supportive.

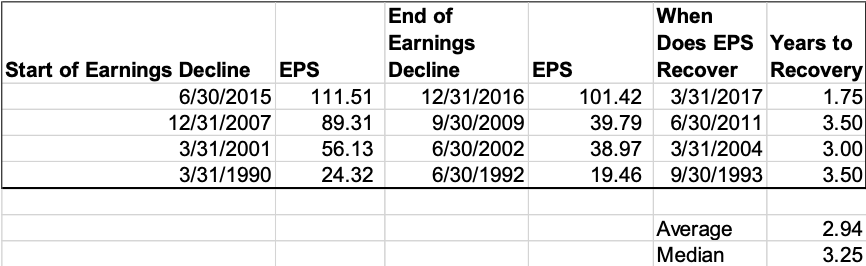

Finally, and the most illuminating, is the history of earnings and their paths after recessions, below in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Trailing 12 Month Operating EPS Peaks and Recoveries

Again, this third point of view reiterates a multiyear recovery is ahead of us. Moreover, look at the variation in earnings declines experienced over the last 30 years. Some are more than 50% declines (the Great Financial Crisis) while others are 20%. Despite vastly different depths in their troughs the market still needed multiple years to strengthen back up to the point of a full recovery. If earnings requires two or three years’ time of recovery then the market that we are facing today is as follows:

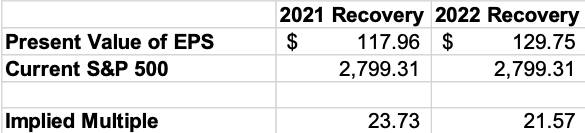

Figure 4: Valuation of Recovery Scenarios

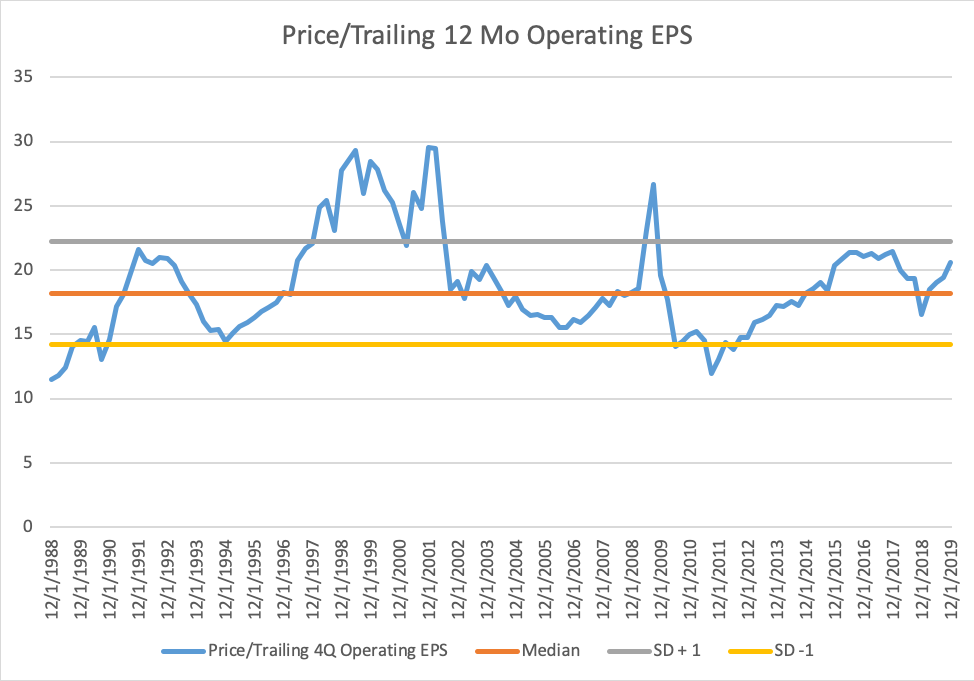

Using 2019’s Operating Earnings per Share of $157 and two scenarios of recovery, we’re able to come to an estimate of what the broad market is currently being valued at based on earnings multiple years out into the future. Neither scenario corresponds to a favorable risk/reward scenario, or, consistent with the quote to start this piece, a “margin of safety” to feel comfortable with. We would be fine paying above average multiples at the trough of earnings declines (whereby you’d be buying accelerating EPS). But the decline hasn’t even begun in 2020 and the broad market is still about 1 full standard deviation above its historical median. Without greater support in terms of valuation, investors who have piled back into the market are playing a risky game.

Many people may argue that we’ve never voluntarily shut down an economy before or that we haven’t dealt with a global pandemic in any sort of recent past. Such reasoning proclaims that because the economic pause has been voluntarily as opposed to a product of economic weakness that a recovery can happen just as quick. That may be true, but we have dealt with exogenous shocks that put the economy into a recession (oil shocks in 1973 and 1990 as well as the terrorist attacks of 9/11 that devastated discretionary parts of the economy). The fact that they were rare, exogenous, inexplicable events didn’t take away from the fact that the economy and the markets needed time to recuperate.

Just as we’re experiencing now, past exogenous shocks suspended economic activity in some way, shape, or form. The pause occurring now is greater in degree. Regardless, in the midst of those contractions the economy undergoes changes that leave it coming out different than how it looked going in. Industries get restructured, jobs get shifted around, and new industries form. That’s why starting an economy is much more difficult than it is to shut it down. Matching employers with labor and capital isn’t seamless because demand is sparse, isolated in pockets, and risk taking sentiment is weakened. In short, if the economy coming out doesn’t look like the one going into a recession, how can anyone expect a recovery to happen quickly? We may come out of the coming recession realizing that some tasks don’t need as much real estate as many people are now realizing as they work from home. Other companies will ask fewer employees to do the same amount of work, and may in the process realize a more efficient way to divide up tasks. Other firms may realize they need more resources devoted to flexible work environments and a mobile work force. Realizations like that push out planning and investment and, ultimately, demand for goods and services that prevents the economy from humming back along at its pre-recessionary pace. Most of all, they take time to assess.

Power plants can be shut down instantaneously, taken off the grid at a moment’s notice and taking electricity off the market. Turning it back on, however, is a gentle balancing act between slowly ramping up capacity with small slices of demand. The economy functions much the same way.

We’re still in the early stages in seeing the ramifications of what this recession will look like and the changes it will bring about. Debates about a V, or U, or W shaped recovery are largely meaningless as no two recessions or recoveries are alike, despite similarities. It’s often best to steer away from proclamations of certainty and instead rely upon opportunities in which a margin of safety provides a greater balance to risk and reward.