There is a drama around the markets’ trauma. Two contradictory messages are being sent simultaneously: Fear is dropping in the equity markets, which have erased losses and are turning positive for the year. At the same time, fear is rising in the global bond markets as debts are rising along with corresponding long-term yields. Normally, those two facts cannot co-exist for more than 12-15 months, until one must give in. When a market element (such as an expected oversupply of long-term bonds) reacts with an oxidizing agent (such as fear of policy), corrosion takes place, the contradiction ends, and one of the two prevails. Welcome to market oxidation, or as Aeschylus would have called it, “Welcome to the drama of Thebes.”

In the play titled The Seven Against Thebes (written in 467 BC), Aeschylus describes the internal civil fight of two brothers for the throne of Thebes. When King Oedipus exiled himself, he left his kingdom to his two young sons, Eteocles and Polynices. However, their uncle Creon ruled Thebes until the sons came of age and agreed to rule in alternate years. When the time came for Polynices to take the throne, Eteocles refused to honor the agreement and exiled his brother Polynices, who found refuge in Argos. Polynices enlisted the assistance of six companions from Argos to battle against his brother Eteocles at the seven gates of the city of Thebes. The chorus pleads with Eteocles – as it is mindful of the longstanding and inexorable curse that has deluged the family in blood – not to slay his brother. Their father had prophesied that his two sons would perish at each other’s hands, and indeed they did at that battlefield, as the messenger proclaims in his report to the chorus and the city.

While their sisters Antigone and Ismene are mourning for their two brothers, a herald arrives announcing that proper burial will be given only to Eteocles (per order of Creon who rose to the throne following Eteocles’s death), and Polynices would not be given a burial as he behaved like a traitor and his body is to be left for the animals to eat. In his hubristic attitude, Creon ignores divine law and the fundamental principles of justice. Antigone proclaimed that she would defy Creon’s order at whatever price, and half of the chorus agreed with her while the other half departed to join Eteocles’ funeral procession.

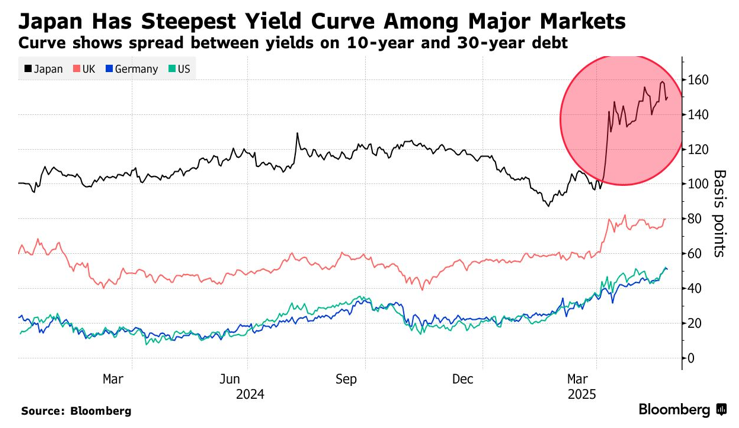

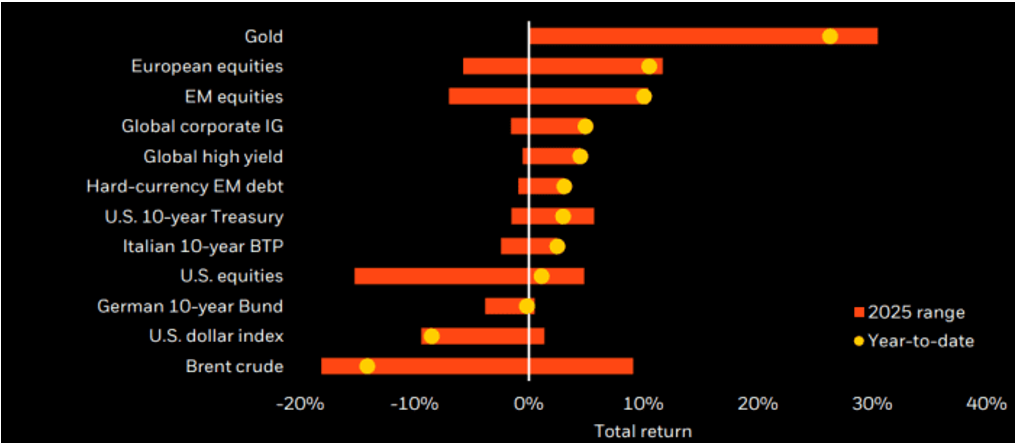

The rising short positions in the long-term Treasury market reflect the traders’ and investors’ beliefs that the selloff in long-term Treasuries could continue. Polynices and the $29 trillion bond market are trying to send a message that defying the fundamental laws of demand and supply for bonds not only could inflict pain via higher interest rates but also bring destabilizing forces via higher costs and lower aggregate demand. The US debt market is not the only one under pressure. The Japanese long-term bond market has been experiencing shocks lately. Demand for Japanese bonds is falling, supply is anticipated to increase, and, consequently, yields are rising. Therefore, we are confronting a global bond market turmoil – as seen below – that may get worse.

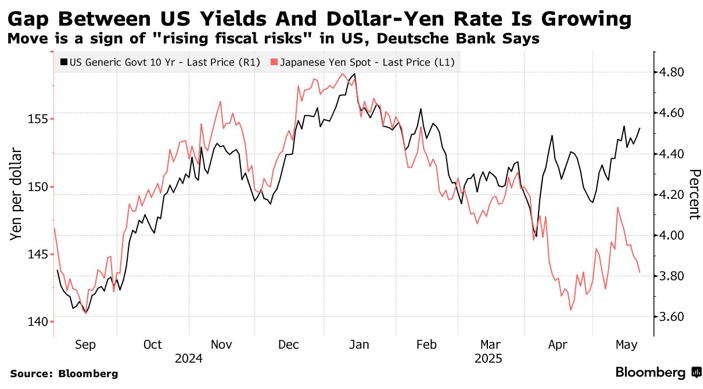

The rising yield of Japanese bonds could act as a competitor to US Treasuries and reinforce the recent dynamic of foreign capital leaving US markets, especially under conditions of a declining dollar. Such departure (especially by Japanese insurance companies and funds, which can now find attractive yields at home) can exacerbate fiscal tremors in the US, pushing the cost of capital to higher levels and undermining a cycle of projected growth. Moreover, when the Japanese yen is strengthening against the US dollar – despite rising US yields – it is indirect evidence of weakening demand for US debt from Japanese and other foreign funds (see below).

Creon exhibits hubris and arrogance while he is unconcerned for the weak and the vulnerable. Aeschylus, in his earliest play that has survived, titled the Persians (written in 472 BC), describes the high drama and tragic consequences of Xerxes’ hubristic behavior motivated by a spirit of revenge and arrogance. In 490 BC, Darius I lost the battle of Marathon. Ten years later, his son Xerxes I demanded revenge and sailed for Greece. At the battle of Salamis, Xerxes I was humiliated. The play describes the Persians’ elders (who form the play’s chorus), while debating about the lack of news from Xerxes’ invasion and expressing anxiety about the king and his invading forces. The king’s mother, Atossa, joins the elders and seeks interpretation of an ominous dream. As they are conjuring, a messenger arrives who announces the destruction of the Persian fleet, while also recounting the suffering of the Persian army on its homeward journey. On learning what had taken place, Atossa sacrifices at the tomb of her husband Darius I, whose spirit appears, warning against any further hubristic plans of invasions and ascribing his son Xerxes’ downfall to his insanely presumptuous obsession with revenge.

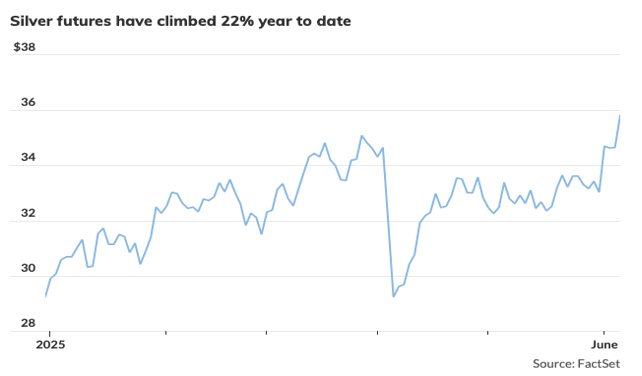

The markets may have already entered a stage where trust and standards have been corroded. Declining foreign capital participation in bond auctions combined with rising yields will eventually result in shaken confidence, at a time when irresponsible policies seem not to carry any consequences, given the equity market’s recovery. That by itself reinforces hubris in an environment that supports moral hazard and capital misallocation, while mispricing risk erodes fundamental metrics of valuation. This is classic Xerxean convoluted strategy of asset allocation underwritten not by rules but by ephemeral emotions. As assets are misallocated, a bull thesis is celebrated, but the battlefield is narrow – like in Salamis – and the ships have limited space for maneuvering. The waters would become even more shallow if foreign capital were penalized, as envisioned in the new tax bill. As investors are chasing returns around a limited number of names, the quality of earnings per share becomes narrower, pushing investors to hedge (hence the higher cost of insuring against default), while seeking alternatives in silver and/or in stablecoins.

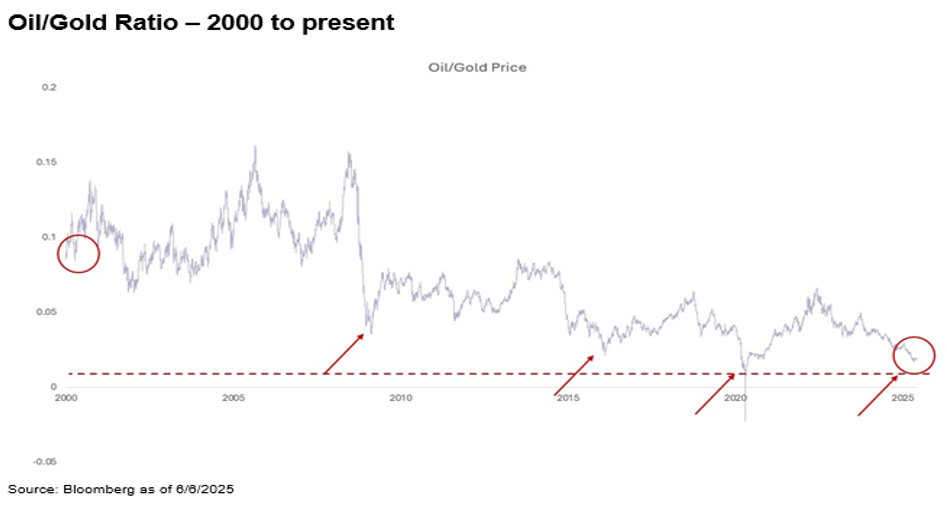

In the midst of all these developments, it is curious to observe that the oil sector has been potentially ignored despite rising geopolitical tensions, especially when we consider it in relation to gold prices, as shown below.

Algernon Swinburne described Aeschylus’ Oresteia (the only surviving trilogy by Aeschylus, written in 458 BC) as “the greatest achievement of the human mind”. It describes the Argive house of Atreus, where one crime led to another over several generations, starting with Agamemnon sacrificing his daughter Iphigeneia in order to receive favorable winds from the gods to sail to Troy. During his ten-year absence, his wife Clytemnestra ruled the kingdom with her lover Aegisthus while sending her son Orestes away. When Agamenon returned, Clytemnestra and Aegisthus assassinated him. The chorus of the elders declared its horror but was silenced by Aegisthus’ threats. The chorus is left with the hope that Orestes will return and avenge his father’s death.

In Choephori (Libation-Bearers), Aeschylus has Orestes return to his homeland at the time when his sister Electra and the chorus are preparing to pour libations at Agamemnon’s tomb. The siblings conspire to avenge their father’s death. Orestes kills Aegisthus and Clytemnestra, however, the Furies (Erinyes) start haunting him and drive him insane. Orestes takes refuge at Delphi under the protection of Apollo, and his matricide crime becomes endurable.

The third play of the trilogy, the Eumenides, opens at Delphi. The Furies have fallen asleep, and Apollo orders Orestes to depart for Athens and seek a judgement there. The Furies are aroused by Clytemnestra’s ghost and start pursuing Orestes. In Athens, Orestes and his pursuers present their arguments in the high court of Areopagus in front of Athena’s temple on the Acropolis and in the presence of the goddess herself. Apollo is the advocate of Orestes, but the judges are equally divided. Athena awards Orestes her casting vote, persuades the angry Furies to calm down, and leads them to their new shrine beneath the Areopagus, where henceforward they will be known as the Kindly Ones (Eumenides).

Despite weak manufacturing data (PMI at 48.5), persistent concerns over inflation, trade tensions, and recession risks, US equities seem to live in their own cocoon, contradicting rising global term premia and debt-servicing costs that are destined to reshape bond markets.

As I was drafting the closing lines of the commentary, I saw somewhere in the distance Aeschylus pointing to the following graph and asking: “Where are the Furies?”

Source: MarketWatch