“So your advantage of scale can be an informational advantage. If I go to some remote place, I may see Wrigley chewing gum alongside Glotz’s chewing gum. Well, I know that Wrigley is a satisfactory product, whereas I don’t know anything about Glotz’s. So if one is 40 cents and the other is 30 cents, am I going to take something I don’t know and put it in my mouth—which is a pretty personal place, after all—for a lousy dime? So, in effect, Wrigley, simply by being so well known, has advantages of scale—what you might call an informational advantage.” – Charlie Munger

“The single most important decision in evaluating a business is pricing power,” – Warren Buffett

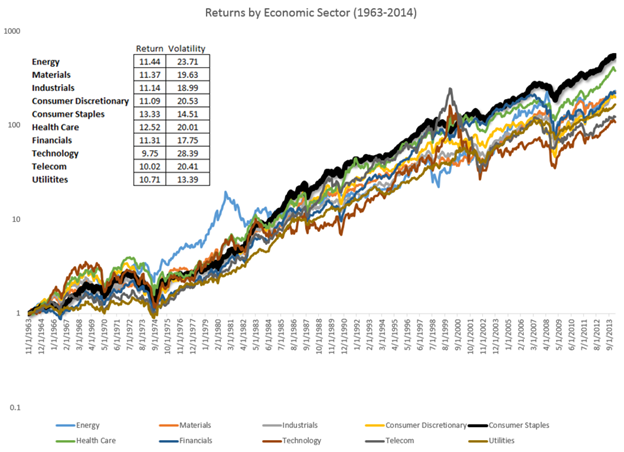

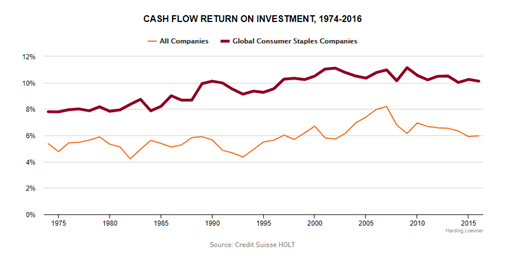

For the better course of the post-World War II era, U.S. markets were dominated by the most basic of products. It wasn’t the creators of innovative technologies or discoverers of breakthrough drugs who posted the best returns for over half a century. Rather, manufacturers of everyday items such as soap, toilet paper, cereals, beverages, cigarettes, and razors were far and away the sector of the economy that posted the best returns, and with the second lowest volatility no less (so much for efficient markets). The returns posted by Consumer Staples (the name given to these everyday items) is not surprising given their Returns on Invested Capital (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Returns by Sector (Investor Field Guide)

Figure 2: Consumer Staples Generate Superior ROIC (Credit Suisse)

But as mentioned in the commentary about the importance of Return on Invested Capital as a metric for investment/business analysis, the presence of superior company economics needs to evoke questions that make investors understand why such returns were able to persist. In the case of Consumer Staples/Consumer Packaged Goods (CPG), investigating the causal structure that enabled these returns for over half a century reveals an environment that isn’t conducive to the same returns going forward.

But as mentioned in the commentary about the importance of Return on Invested Capital as a metric for investment/business analysis, the presence of superior company economics needs to evoke questions that make investors understand why such returns were able to persist. In the case of Consumer Staples/Consumer Packaged Goods (CPG), investigating the causal structure that enabled these returns for over half a century reveals an environment that isn’t conducive to the same returns going forward.

Vibrant brands have historically been a tremendous source of value creation in the CPG space. As the Munger quote alludes to, the advantage these companies possessed, in many ways, comes down to scale. Companies like Procter & Gamble provided generations of households with goods offering predictable, low variance performance for everyday tasks. As a consumer, knowing a product meets your individual needs saves time and energy. In economic theory, we refer to this effort by consumers as enduring Search Costs: costs paid in trying to determine what to choose/purchase. Sean Stannard-Stockton at Ensemble Capital explains the phenomenon well:

“In the case of a consumer packaged good like canned food, toothpaste, or laundry detergent, the search cost for consumers is the cost of trying to determine the quality of the product and weighing this against price differentials prior to purchase. By eliminating this cost for the consumer, companies with a successful brand were able to charge more for their products, even while providing an improved cost/benefit offering to the consumer. The consumer could pay more for their products, because doing so reduced the search costs they were otherwise incurring.”

Companies supported brands with clever and relevant marketing to build loyalty with their consumers, setting up repeat purchases.

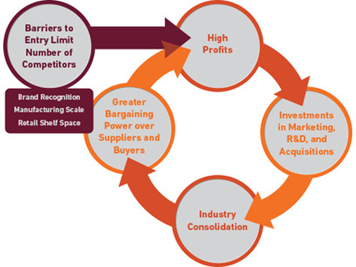

But both getting a product on shelf and building supporting marketing campaigns was only available to the largest of players. The retail industry has always been one that survived on razor thin margins. Carrying product that sat on shelves and wasn’t purchased was like setting cash on fire. Thus, only the best-selling items got stocked; items that retailers knew consumers would buy. Second, building the loyalty in the minds of consumers was a massive undertaking for the better part of 50 years. Buying advertising spots for national campaigns was enormously costly, only affordable to the deepest of pockets. Figure 3 spells out the flywheel at work, whereby superior scale meant the ability to win mindshare via advertising and marketing, translating to consumer demand at retailer shelves. Guaranteed demand from consumers gave CPG firms the ability to consistently raise prices year after year above inflation producing excess profits (see the Buffett quote about pricing power) and excellent margins. Those excess profits got poured into marketing, advertising and some for R&D, so that the next wave of products could continue to feed the cycle. Finally, a third benefit these businesses had is their minimal capital intensity. Coca-Cola didn’t need to build a new plant to create Diet Coke and General Mills didn’t have to start from scratch to produce Honey Nut Cheerios after the original. With minimal additional capital outlays these companies created new products, expanded the universe of potential customers, and raised sales, all on costs that had been invested years before.

Figure 3: Consumer Packaged Goods Flywheel (Harding Loevner)

Pricing power + Huge Barriers to Entry + Minimal Capital Intensity = Superior Returns. That was the formula for incredible businesses centered around consumer brands and the moat that protected it was the massive marketing scale needed to launch a national brand and to stock shelves. Emphasis on was.

Slowly, this formula has unraveled thanks to a variety of forces for the past twenty years but the most powerful has been the various new ways consumers can get information or be influenced into purchasing a product and how they buy. Online peer reviews for online shopping sites such as Amazon and eBay have been around for over two decades; this direct peer testimony on a new shopping experience accustomed consumers to finding new ways to learn about goods. While they may have been buying the same products as prior generations, the habit of being informed via a channel outside traditional advertising mediums was brand new. Over time, other mediums for engaging with brands and products emerged, namely Facebook and Google, but the general concept is that the birth and eventual ubiquity of the Internet reduced the grip old advertising channels had on holding consumer attention. Concurrently, ecommerce has become a norm, evident by the fact that over 80% of American households possessed an Amazon Prime membership, giving them access to free 2-day shipping on millions of items.

The presence of new ways to discover, engage with, review and purchase brands meant one simple thing: the cost to launch a brand has deteriorated drastically. Look no further than the rise of Dollar Shave Club over the past decade. In 2010, Procter & Gamble’s Gillette brand had 70% share of the men’s razor category; a high margin, recurring purchase item with incredible brand loyalty that allowed for price increases every year. Dollar Shave Club launched with nothing more than a YouTube commercial that cost them $4,500 to produce, a far cry from the multiple millions that P&G paid for marketing campaigns. The savings allowed them to undercut the category leader on price and provided a new value proposition thanks to an easier shopping experience. Since that launch, P&G’s Gillette brand has lost over 17% of market share, took a write-down of $8 billion, and had to cut prices, an unheard of move for the brand and one that shocked the price of P&G’s shares.

The story of Gillette and Dollar Shave Club plays out similarly in so many other categories (diapers, tissue paper, carbonated soft drinks, packaged food, etc.), especially as multiple generations of American consumers have also now grown accustomed to Private Label, further accelerating the pressure on brands reliant on reducing search costs. The result is exactly what basic economic theory would suggest. As the cost to launch a brand has collapsed, the supply of them has exploded. Firms can segment consumers with specific solutions to niche needs, as opposed to providing mass, one-size-fits-all solutions. As a result, the landscape for companies offering brands whose value comes from reducing search costs has become much more competitive and with greater competition comes the inability for the companies to consistently raise prices year after year going forward. Procter & Gamble, Colgate Palmolive, Coca Cola, and many others all have lower sales now than they did in 2014 and are now spending greater percentages of revenue on marketing, crimping margins.

With the internet and ecommerce becoming such a second nature activity for millions of consumers the competitive backdrop will not get easier over the long-term for many names. As a result, increased costs are likely to stay, becoming a fixed, static nature of doing business all while the shopping environment gets more complex and diverse. This formula spells a gloomy outlook for search cost brands going forward over the long term, constraining the ROIC they generate on their assets and consequentially the returns their equity will be able to generate going forward.