Thomas Mann was the recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1929. His novel titled Buddenbrooks has been credited for such success. The novel chronicles the decline of a German bourgeois family. In a similar fashion recent signs of significant slowdown in China and India and the persistent economic weakness in Japan, raise questions as to whether this century will belong to Asia as originally thought.

We will try briefly to outline below some basic facts about the Asian Buddenbrooks dilemma, and we shall start with China. The economic growth slowdown is a documented fact in China. It seems that the engine of growth i.e. exports is not firing up at full speed any more. There has been an exodus of low-cost manufacturing facilities to other Asian countries such as Vietnam, the Philippines, Cambodia, Laos, etc. The EU problems have made the situation worse since exports to the EU have been declining. China is in the process of a rebalancing act. The change in leadership may not be as smooth as expected. Higher wages are demanded and the geostrategic tensions with Japan may prove to be lethal in a few years.

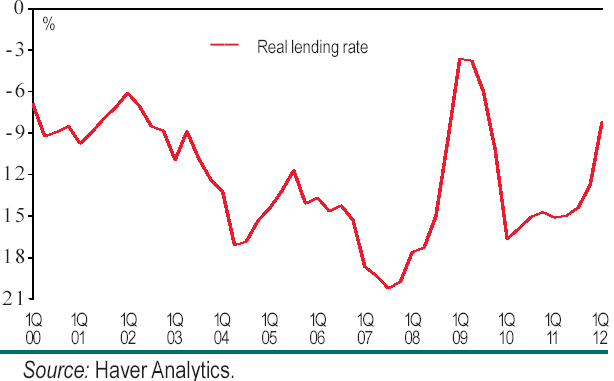

In our September 2010 newsletter, we had pointed out the bubbles in China and the great wall of steroids that was and is unhealthy for the Chinese economy. As the graph shows below, the real lending rate is China remains negative, a fact that misallocates capital, feeds imbalances through excess investments in fixed capital, and creates bubbles.

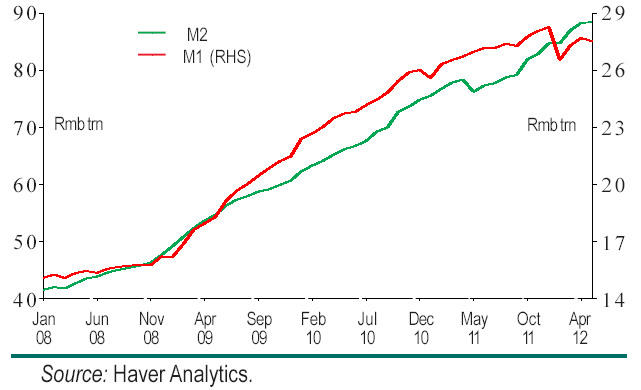

Also, as the following graph shows, the money supply (and not just the reserves as it happens in the US or the EU) keeps growing at a significant pace, boosting the chances that a tremor could bring in a tsunami of a hard landing.

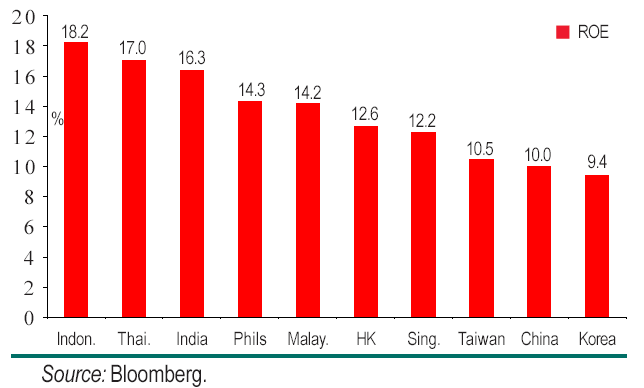

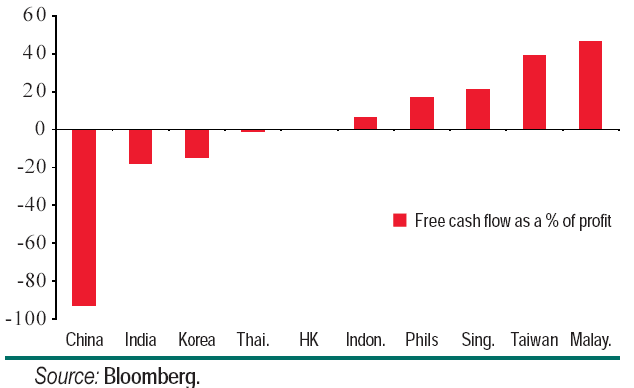

Besides the macro-fundamentals above, we should also point out that on a corporate level the return on equity is among the lowest in Asia and the free cash flow as a fraction of profits is negative, as shown below.

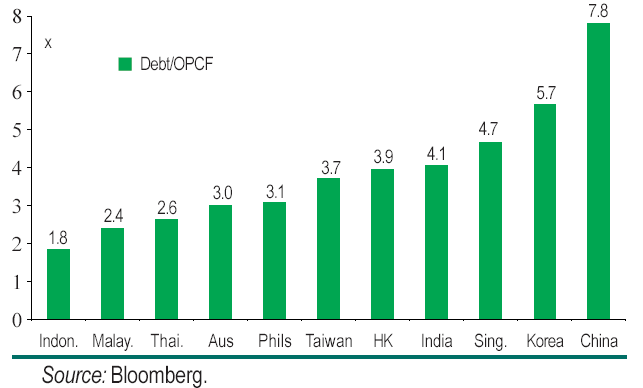

The low ROE signifies declining profit margins. Actually profit growth is decelerating at a rate close to 50%. At the same time capital expenditures are outpacing profit growth, a phenomenon that undermines companies’ balance sheets. Moreover, a deterioration in the working capital cycle as exhibited in the median receivable days and the inventory turnover signifies that as inventories accumulate, there is a rush to record revenues but delay in recording costs. All of these have resulted in cash outflows as shown above. The result is that operating cash flow as a percentage of profit is the lowest in Asia. The next figure is troubling for corporate balance sheets in China.

The figure above shows that the debt to operating cash flow is the highest in China (implying declining ability to pay off debts). If a tsunami comes it could devastate many Chinese companies.

Moving now on to India, as a first observation we would say that not only did the growth rate slowed down by almost 60% recently , but also there are persistent inflationary pressures, a combination of which points to potential stagflation. Thus, while recent measures are encouraging (in terms of attracting FDIs and other investments), and steps are taken that point to fiscal consolidation, and India’s exposure to external trade risks is lower than that of China’s and Japan’s, the idiosyncratic risks are such that the announced reform agenda cannot overcome. Specifically, as the following figure (from the Central bank of India) shows, inflationary expectations approach 13%.

Such inflationary expectations lead to malinvestments and work against capital and wealth formation. If they materialize in a self-fulfilling scenario, then stagflation may move India into circles of higher unemployment, lower capital expenditures and reduced productivity. Hence, while India’s corporations have better debt-to-cash ratio, and enjoy greater ROE than Chinese firms (see graphs above), the stagflationary forces may lead to greater free cash outflows which will backfire in the efforts to generate higher growth, employment, and incomes.

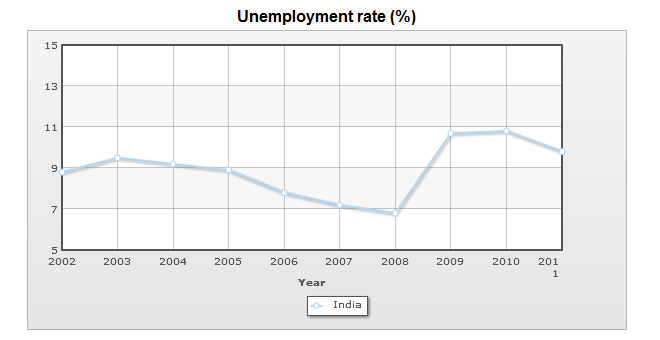

Of course, as stagflation takes hold of capital expenditures and investments, the unemployment rate (already at almost 10%, as the graph below shows), will start rising again, and that a vicious cycle will start.

The result of such vicious cycle is that the declining trend in business confidence will continue, as the figure below shows.

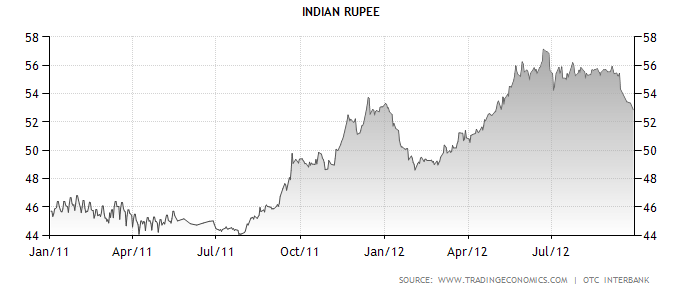

The declining business confidence coincides with a declining currency which reinforces inflationary pressures, as the figure below demonstrates.

We are of the opinion then, that unless the stagflationary pressures are addressed in an adequate way, India along with China (the latter for reasons explained earlier) may no longer belong to the BRIC category and would rather exhibit Buddenbrookian characteristics.

As a closing note we should state that we are cautious regarding the medium term. Hence, while in the short term the QE measures worldwide reduce tail risks, the global demand remains weak, risk aversion is expected to resurface, global imbalances have not been addressed, while enormous debts will make investors pause as to their risk-taking appetite. In that environment emerging markets are predicted to perform poorly.